WASHINGTON -- Should Democrats focus on winning back political independents, and should their strategy focus on greater bipartisanship? That's the message of a recent Washington Post report which tells us that advisors to President Obama...

...are deeply concerned about winning back political independents, who supported Obama two years ago by an eight-point margin but backed Republicans for the House this year by 19 points. To do so, they think he must forge partnerships with Republicans on key issues and make noticeable progress on his oft-repeated campaign pledge to change the ways of Washington.

In a new column, The New Republic's John Judis disagrees, grounding his analysis in a useful review of what political science and survey research have to say about who "independents" are and why they vote the way they do. While much of the change since 2006 has likely occurred in the middle of the political spectrum, Judis reminds us of the danger of treating "independents" as a single cohesive group.

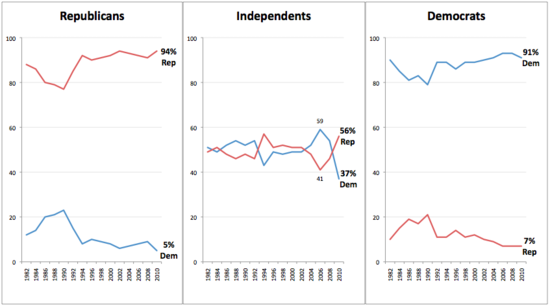

Let's start by considering the most compelling data to support the post-election focus on independents. According to the National Election Pool exit polls, most of the change since 2006 can be accounted for by shifts in (and growth of) the independent subgroup. As the graphic below shows, Democrats and Republicans voted for their respective parties by roughly the same margins as they have for the last ten years or so, but their independent subgroup reversed dramatically, going from an 18-point Democratic advantage in 2006 (59% to 41%) to a 19-point Republican win (56% to 37%) in 2010. (Note: The chart is modeled on the invaluable compilation produced by the New York Times, and uses the data they published, updated with a more recent weighting of the 2010 exit poll data published by CNN).

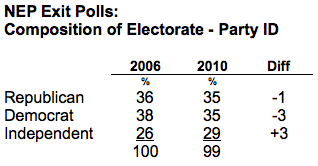

But is it possible that that the overall change since 2006 was the result in a different composition of the electorate? In other words, did the proportion of Republican voters surge in 2010 as compared to 2006? As measured by the exit polls, the answer is no, although there were fewer Democratic identifiers and more independents. As the table below shows, the number of Democratic identifiers dropped three percentage points (from 38% to 35%), but it was an increase in independents (from 26% to 29%) that made up the difference. The number of Republican identifiers actually dropped a single point (36% to 35%).

Enter John Judis who provides a helpful summary of what political science and recent survey data have to say about "independents" as measured by opinion polls that should give us some pause about interpreting the exit poll results too literally:

- Party identification, as measured by the exit polls and most national surveys is "a creature of pollsters' imagination" -- based on a question about how voters think of themselves, not about status or formal membership in an organization.

- Many independents do not vote.

- The majority of those who initially identify as "independents" on are really "disguised partisans" -- or "leaners" in the pollster lexicon -- who vote reliably for one party or another.

- Only about a third of independents are truly "swing voters who are not dependable partisans."

If the term "disguised partisans" among the independents sounds familiar, it is because you have heard it before from me and (more often) from John Sides, the George Washington University political scientist who runs the Monkey Cage blog. In a post earlier this week, Sides argues that the 2010 story "is about Republican-leaning independents." Sides points to data from Democratic analyst Ruy Teixeira, who finds that Republican-leaning independents have grown more conservative since 2006, while the number of conservatives among rest of the "independent poll" has not changed or decreased.

Unfortunately, the exit polls do not ask the follow-up question that probes independents on how they lean. However, we can turn to a reasonable facsimile in the form of the large final weekend samples of "likely voters" interviewed by the Pew Research Center in 2006 and 2010 (which produced highly accurate estimates of the two party vote in each year).

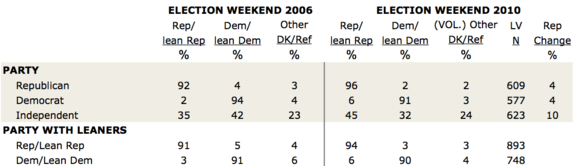

First, the Pew Research results, reproduced below, show only a slight change in vote preference among the standard "no leans" categories for Democrats and Republicans, with a ten-point shift to Republicans among the larger group of independents (including those who lean to one party or another). However, cross-tabulations also include results among all partisans including party leaners, and these also show relatively little change since 2006. While the tables do not break out the preference of "pure independents," the numbers imply relatively large shifts in vote preference since 2006 among those who lean to neither party.

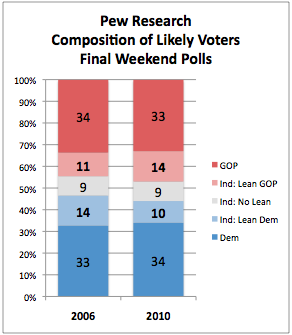

But such comparisons may be misleading, as the same surveys imply that the composition of the "pure" independent group may have changed considerably since 2006. Consider the following chart, which shows the partisan composition of the final Pew Research surveys in 2006 and 2010. Most of the change since 2006 is within the independent category: As a percentage of all likely voters, Republican leaners grow by three points (from 11% to 14%), while Democratic leaners shrink by four (from 14% to 10%). So the "pure" independent group in 2010 probably includes a lot of former leaners from 2006.

What complicates this sort of analysis is that three things are changing at once: (1) some voters are shifting among the party identification categories, (2) some turned out to vote in 2006 but not 2010 or vice versa and (3) some changed their vote preference, shifting from support of one party to another since 2006. So it is difficult to conclude from these data that "the story" is about one particular category of voter. That said, the data before us imply that all three kinds of change are happening among voters in the middle third of the electorate -- those who are less engaged in politics and whose attitudes and preferences are less rooted in strong partisanship.

Back to the Judis analysis, which mines another highly relevant Pew Research Center survey conducted this past September for some useful conclusions about the true "swing voters" among political independents:

[T]he most important feature of [swing voters] is not that they call themselves "independents," but that they belong to a social group that since the 1970s has become an important swing vote. What happened in this November's election is that many white working-class voters, including white working-class women, voted for Republicans rather than Democrats. As the Pew poll anticipates, that undoubtedly held true among white working-class voters who described themselves as "independents."These swing voters are probably one of the two groups that swelled the ranks of independents this election--up to 29 percent in this year's exit polls from 26 percent in 2006--and tilted the vote to the Republicans. The other is probably the Shadow Republicans, which included voters who had previously considered themselves Republicans, but were alienated by George W. Bush's second term.

Judis then considers whether a special strategy exists "that Democrats can use to win over these white working-class independents," and reviews evidence that when "faced with an economic downturn, they will oppose the party that they hold responsible for it." His analysis echoes Sides, who concludes that "voters -- independent or otherwise -- do not put political process ahead of outcomes." Judis concludes with this strategic prescription:

Yes, Obama does have to pay attention to those white working-class voters who shift uneasily from one party to the other, but the way to win them over is to get them jobs--and if that fails because of Republican obstructionism, to make sure that these voters blame the Republicans not the Democrats and his administration for the result. If he can't do that, his only recourse may be to get on his knees and pray that unbeknownst to most voters and many economists, a strong and buoyant recovery is about to begin.

Sides and Judis are absolutely right when they argue that outcomes and economic performance matter far more to true swing voters than the political process. But whether you agree or disagree on strategy, the most important take-away is that not all self-identified independents are created equal.

Follow Mark Blumenthal and HuffPost Pollster on Twitter