WASHINGTON -- Fewer people were out of work for longer than six months in October, which could signal that the long-term jobless are finding jobs. But maybe not.

The number of long-term unemployed fell 366,000 to 5.9 million, the Labor Department announced Friday. But since it first topped 6 million at the end of 2009, the size of the population coping with six or more months of joblessness hasn't changed much. The latest datapoint represents the third time the number of long-term jobless dipped below 6 million this year. Each of the two previous times, it went back above 6 million the next month.

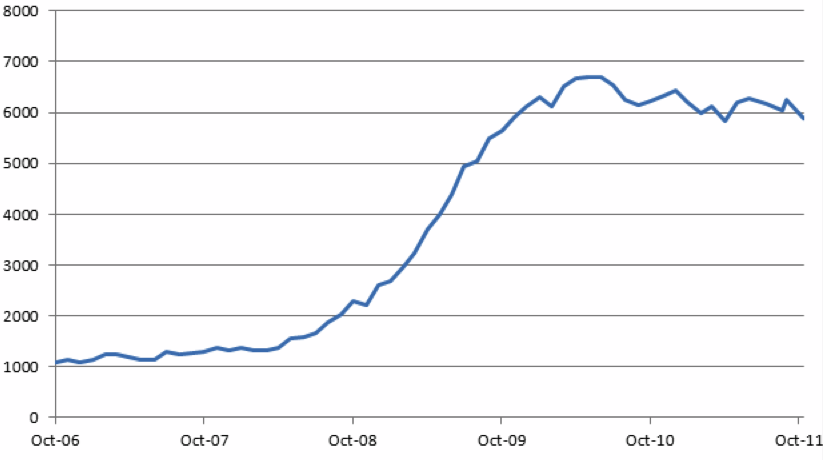

In other words, October's decline in long-term joblessness is small potatoes. The below graph, from economist Heidi Shierholz of the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal D.C. think tank, shows the trend in prolonged unemployment since 2006.

"There is a lot of month-to-month variability in these numbers," Shierholz said. "It's just been hovering around 6 million for the last year."

Shierholz said there were 4.4 million people who'd been out of work a full year in October 2010. That number has fallen to 4.1 million. But the number of very long-term jobless -- people out of work 99 weeks or longer -- tells a more a discouraging story.

At this time in 2010, there were 1.5 million jobless who'd passed the 99 week mark. Now there are 1.8 million. (There were 2 million in September, but since these particular data on unemployment duration are not seasonally adjusted, month-over-month comparisons don't really work.) The 99 week milestone is significant because once someone's been out of work that long, he or she no longer qualifies for unemployment insurance.

To be counted as unemployed, a person has to actively search for work -- so declines in unemployment could reflect people finding jobs, but they could also reflect people giving up their search out of hopelessness. Because people must search for work as a condition of receiving compensation, the benefits could inflate the number of unemployed. The most recent research on the topic, an analysis by Berkeley economist Jesse Rothstein, found that extended benefits raised the jobless rate somewhere between 0.2 - 0.6 percentage points, mostly because the benefits kept people from giving up on their job searches.

The White House has estimated that 4 million people will run out of benefits this year. Congressional proposals to create additional weeks of benefits have gone nowhere.

Democrats in Congress want to reauthorize the current regimen of extended compensation, without which the maximum duration of benefits will fall to 26 weeks. Republicans haven't yet indicated whether they plan to cooperate.

Arthur Delaney is the author of "A People's History of the Great Recession," HuffPost's first e-book.