Over at the Atlantic, Derek Thompson has a fun piece up titled "When Good Companies Have Bad Ideas." Riffing on the magazine's recent "Killer Ideas" issue, it includes a slideshow of some of the most celebrated examples of product innovations that crashed and burned upon entry to the marketplace. (Anyone remember Coors Water? Actually, you are probably reminded of it painfully every time you have the misfortune to drink Coors "Beer.")

Of course, no compendium of bad ideas is complete without New Coke, and Thompson does not disappoint:

As Malcolm Gladwell recounted in his book Blink, Coca-Cola responded to Pepsi's eponymous "challenge" by trying to make a sweeter soft drink that could actually win the Pepsi Challenge. This turned out to be a wild misreading of its own strengths. In retrospect, Pepsi was probably winning the taste-test battle for the same reason that Coke was winning the soda war. Coke's milder, prune-y flavor goes better with a steak over dinner. At the end of the day, the only people drinking soda in shots were the handful of young people filmed playing the Pepsi Challenge.

By pure coincidence, the recent inability of the so-called 'super committee' to come to an accord about what to do about curbing the federal deficit has had me thinking about the 'New Coke' debacle quite a bit. See, as the super committee deliberated throughout the fall, I feel like the media got us locked into this notion that if they were unable to come up with a plan that all of its members could agree to, this constituted a "failure," while an approved-by-super-committee strategy for curbing the debt constituted a "success."

The problem with that thinking is that there was never any indication -- or even a shred of evidence -- that suggested the super committee was in any way poised to deliver a competent plan, let alone an intelligent one. So it's difficult to understand why anyone was actually looking forward to the product they might have produced with optimism, or imagined for even one minute that those 12 members of Congress had the capacity to alter our longterm budget trajectory in some sort of optimal way. What's been deemed a "failure," for all anyone really knows, may have actually been a dodged bullet.

The New Coke comparison is useful in this situation because while the product that the Coca-Cola Company produced in 1985 is now considered to have been an unalloyed failure, there was a hot minute or two when the folks that conceived and executed the idea were thought of as geniuses and company saviors, and the product was deemed a self-evident success. As Mark Prendergast documents in his book, "For God, Country and Coca-Cola: The Definitive History of the Great American Soft Drink and the Company that Makes It," when CEO Roberto Goizueta was asked if he'd be changing up Diet Coke's formula "assuming [New Coke] is a success," he replied, "No. And I didn't assume that this is a success. This is a success." Sounds to me like a guy who got himself prematurely locked into a concept of "success."

Of course, Coca-Cola's course correction was to reintroduce the old formula (sort of -- cane sugar was swapped out for high-fructose corn syrup) to the marketplace. That move, by contrast, was deemed a success -- so much so that it wasn't uncommon to hear people theorize that this marketing debacle was actually a genius bit of misdirection. Whether you believe those conspiracies or not, the simple fact of the matter is that it sure was a complicated way of succeeding by changing nothing at all.

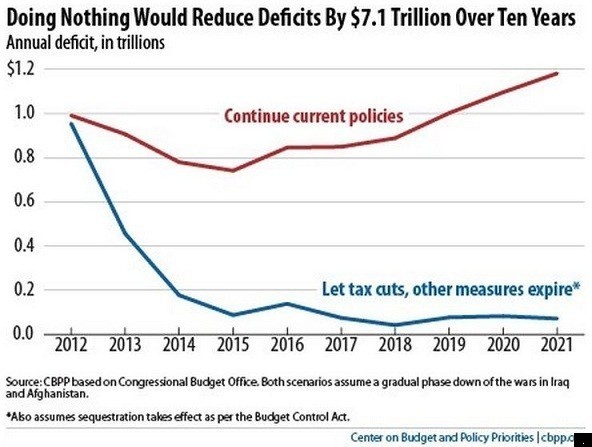

Happily, here is another useful super committee comparison, because at the moment, changing nothing at all remains a superior policy option than anything the super committee would have likely devised. So, I suggest we all celebrate their inability to do something as a pause that refreshes, and get down to the business of doing nothing about the deficit.

Flickr photo by Like_the_Grand_Canyon.

[Would you like to follow me on Twitter? Because why not?]