WASHINGTON -- Newt Gingrich holds himself up as a model of fiscal discipline. "If the U.S. government was as debt-free as I am, everybody in America would be celebrating," he told reporters last year.

What may be true for Gingrich personally, however, has rarely been the case for organizations he runs. Gingrich's presidential campaign is basically broke. The latest financial disclosure reports show that his campaign closed out the month of January with $1.73 million in debt and a scant $1.79 million in cash on hand, just enough to cover expenses that included private jets and unusually large personal reimbursements. The highly publicized injection of more than $11 million from casino magnate Sheldon Adelson into a super PAC backing Gingrich's campaign has fueled the perception that Gingrich is flush, but Adelson's money won't keep the lights on at campaign headquarters.

Instead of withdrawing from the race, as candidates typically do when they run out of money, Gingrich has barreled ahead. In the past month, he has hired additional staff, made costly trips to California and Arizona, and scheduled a week's worth of campaign appearances in Tennessee and his home state of Georgia ahead of the March 6 Super Tuesday primaries.

Gingrich, who did not respond to questions from The Huffington Post, is by no means the first presidential candidate to run up dangerously high debts on the campaign trail. Where the former House speaker is concerned, however, this combination of mounting bills, shrinking prospects and questionable expenses has three decades of precedent behind it.

Interviews with Gingrich's former colleagues and a review of thousands of official documents by The Huffington Post reveal a previously unexplored side of his career: a striking pattern of financial mismanagement at the political and nonprofit groups that Gingrich has created, steered and abandoned over the past 30 years. While the high-profile ethics investigations of the 1990s focused on the narrow legality of Gingrich's individual schemes, their disastrous record as a whole has been largely overlooked.

Since 1984, Gingrich has launched 12 politically oriented organizations and initiatives based in Washington. Of those, five have been investigated by the Internal Revenue Service and the House Ethics Committee, another five closed down with debts totaling more than $500,000, and two were subject to legal action.

According to former colleagues and subordinates, Gingrich burns through money by repeatedly expanding his plans and ignoring warnings from staff about the finances of his projects. Now, the same pattern is threatening his presidential campaign.

"The best way to say it is that Newt has no brakes and no rear view mirror," observed one former adviser who still speaks highly of Gingrich, but who requested anonymity because he is forbidden from speaking to the media in his current job.

"So he never pulls back, and he never learns from the past."

That criticism may be missing the point, however. "Part of the reason Gingrich employs nonprofits and 527s [political advocacy groups] so liberally is that the debts from these groups never attach to him personally, because they're incorporated," said Bill Allison, editorial director at the Sunlight Foundation, a nonprofit political watchdog group. "That's the beauty of sticking to all these groups -- it's that they don't stick to Gingrich."

'WHEN I SEE SOMETHING ISN'T WORKING, I CUT MY LOSSES'

According to a veteran adviser, Gingrich's first deadbeat operation was a 501(c)3 nonprofit called the American Opportunity Foundation (AOF), which he created with a group of political consultants in 1984, during his third term as a Republican congressman from Georgia's 6th District. (A 501(c)4 group, American Opportunity Inc., was created at the same time, but never utilized.)

The mission of AOF was to conduct nonpartisan research, according to its IRS incorporation papers. The group's research topics, however, were rife with political buzzwords, such as how to lessen "the burdens of government."

The conflict between AOF's stated purpose and its real activities came to a head less than a month before the 1984 election, when reports surfaced that AOF had staged events on college campuses hailing President Ronald Reagan's achievements. The law expressly forbids 501(c)3 nonprofits from participating in political campaigns to the benefit of one candidate or another.

The bad press resulted in questions about AOF's legitimacy. Gingrich quickly stepped down as AOF's chairman and severed his ties to the group.

The campus events had cost approximately $15,000, equivalent to $33,900 today, and Gingrich left the bill for his two lead consultants, business partners Ladonna Lee and Henry "Eddie" Mahe. Mahe and Lee expected Gingrich to bring in donations to pay for the events, according to a source close to AOF.

"Eddie and Ladonna were screwed by him," said the source. "I remember Ladonna telling Eddie, 'If you get involved with Newt again, I'm dissolving our partnership.'"

Today, Mahe and Lee are employed by the law firm Foley & Lardner, where Lee is vice chair of the government and public policy practice and Mahe is a strategic communications consultant. Mahe declined to comment for this story, but Lee said she could not recall specifically how AOF ended or whether there were any leftover debts.

"I fully appreciate the role of nonprofits and their success ratio," she said, adding that she had voted for Gingrich in the Colorado Republican primary earlier this year.

When asked whether AOF had fulfilled its mission, Lee paused. "I don't know that it lived out its mission," she said, "but I do know that Newt was never part of the business dealings of any of these entities, and I never saw Newt in a meeting about business."

Although Lee may have intended her comment to absolve Gingrich of responsibility for the debt left at AOF, other longtime Gingrich associates say that it is precisely this lack of financial involvement, coupled with his willingness to abandon initiatives abruptly, that lies at the core of his management problems.

Lee herself described Gingrich's pattern of abandonment in a 1995 Vanity Fair interview, saying, "Gingrich would always get people started on a project or a vision, and we're all slugging up the mountain to accomplish it. Newt's nowhere to be found. … He's gone on to the next mountaintop."

A consultant who worked with Gingrich in the 1980s said, "I heard a staffer question Newt about a cost that was over budget once, and instead of telling the kid what to do next, Newt just said, 'When I see that something isn't working, I cut my losses.'"

Following the demise of AOF, Gingrich turned his energies to the American Campaign Academy (ACA), a group founded in 1986. The academy was funded by the National Republican Congressional Committee, and it ran a 10-week, nuts-and-bolts course on campaign management. Gingrich taught part of the course during his fourth term in Congress, and a number of his associates and staffers served on the academy's board.

Like AOF before it, ACA hoped to receive 501(c)3 nonprofit status so its donors could deduct contributions to the group from their income taxes. ACA's application for tax-exempt status touched off an unexpected, high-profile battle with the IRS, however, that ended when a federal court decided that ACA's purpose was more political than purely charitable and that it had misrepresented its real intent in its application. The IRS, the court ruled, was correct in denying ACA tax-exempt status.

After three years of operating with money from the NRCC while the IRS case wound its way through the courts, ACA dissolved in 1990, less than 12 months after the final decision was handed down.

'NEWT WANTED TO SEND THEM NEWT'

Gingrich wrote in his 1998 memoir, "Lessons Learned the Hard Way," that by the time ACA closed, he knew that the Republican Party "needed alternative means of communication than just the mainstream media" to broadcast its political agenda.

By 1989, as the House minority whip, he had begun devising a new way to use his leadership PAC, dubbed GOPAC, to "disseminate" a "full-fledged, intellectually complete doctrine" that he was creating for the Republican Party, according to a GOPAC memo from November of that year.

The ideas would come from Gingrich, of course, which left only the question of how to fund the dissemination part of his master plan. He later wrote in his memoir that he was inspired by a 1989 exposé in National Journal about how "certain politicians had been using tax-exempt organizations to finance some of their activities."

Gingrich said the scale of the overlap between members of Congress and nonprofits was "astonishing," and although the article was meant as an indictment of the practice, he apparently saw it as a primer. "Thus, when it came time to expand our mission by having me teach a new course," he wrote, "I felt we had ample precedent for how to proceed."

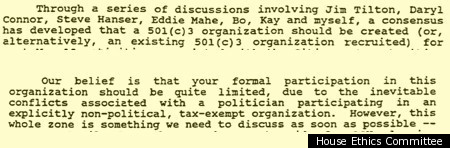

Jeff Eisenach, a GOPAC consultant and former Reagan White House budget aide, wrote in a memo (below) to Gingrich that "a consensus has developed" among Gingrich's cadre of advisers "that a 501(c)3 organization should be created (or, alternatively, an existing 501(c)3 organization recruited)" to help fund GOPAC's expanding mission. This memo and hundreds more were presented to the House Ethics Committee during its investigation of Gingrich in the 1990s and are available on the committee's website.

Among the options, Eisenach wrote in the memo, was "re-activing" a 501(c)3 nonprofit, the Abraham Lincoln Opportunity Foundation (ALOF), that had been founded in Colorado by GOPAC's chairman, Bo Callaway. Originally intended to benefit inner-city kids, ALOF had been inactive for nearly a decade. It was essentially a shell company.

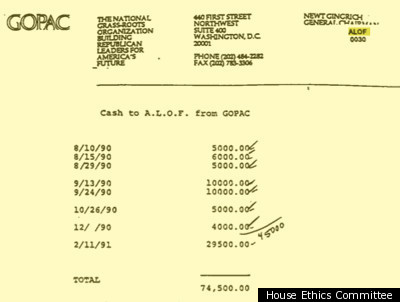

With Callaway's permission, beginning in 1990, Gingrich and his GOPAC staff used ALOF to produce teleconferences and a TV program that would eventually evolve into a college course -- all designed by Gingrich and GOPAC staff, and paid for with a complex mix of political donations to GOPAC and charitable contributions to ALOF. Like other Gingrich projects, this one would grow exponentially over the next three years.

"In some ways, Gingrich has always had grandiose ideas, and he's very good about getting people excited about them and garnering donations," said Allison. "But what he hasn't been able to do is follow through on them. He has these ideas and begins to execute them, and then he moves on."

In a memo to Callaway about GOPAC's future, Eisenach recalled a walk he took with Gingrich in June 1990. "Newt empowered us to think big," he wrote, "and said 'institutions should be invented to meet the environment, not evolve incrementally.'" Those "institutions" would come to include nonprofits, political action committees, and consulting groups.

By August 1990, expenses were snowballing. ALOF had spent more than $260,000 on a teleconference called the American Opportunities Workshop in the first half of the year, much of it collected from GOPAC donors or lent by GOPAC, according to House Ethics Committee documents. GOPAC itself spent another $188,000 on the workshop and a follow-up entity, American Citizens TV. The political action committee was quickly running out of money.

Leadership PACs like GOPAC have traditionally been used to fund other candidates' campaigns, as well as to pay expenses such as the PAC chairman's travel to stump for those candidates. By the summer of 1990, however, GOPAC coffers were so depleted from the cost of producing and distributing Gingrich's message through ALOF and other initiatives that Eisenach, who by then had taken over day-to-day operations, was forced to write revised financial plans with the words "projection based on giving no cash to candidates" at the bottom.

"Instead of sending [candidates] money, Newt wanted to send them 'Newt,'" explained a former adviser who still works in Republican politics and requested anonymity in order to discuss his former boss. "All his ideas about how to run, how to communicate that to voters, I mean, this whole thing he was hatching in his head. And later he decided he wanted to send everything he'd sent all those prospects … to the whole country."

During the 1992 election cycle, GOPAC received more than $4 million in donations and spent only $18,000 on supporting candidates. Nevertheless, the group was left with $340,000 worth of debt at the end of '92.

In December of that year, Eisenach, as director of GOPAC, wrote a damning memo to his superiors, including Gingrich, explaining what few could have imagined: The leadership PAC of the minority whip of the House of Representatives was barely able to make payroll.

Two former aides said Gingrich was well aware of GOPAC's projected shortfall in the summer of 1992, and as Republican hopes for winning the White House dwindled that fall, prospects for fundraising grew slimmer as well. Nevertheless, Gingrich ordered staff to continue spending as though the organization were fiscally sound.

"Sure, Eisenach told Newt that there was no money," said one staffer, "but Newt just said, 'Keep spending.' He said it was 'pedal to the metal' until the election."

'NEWT LEAVES ALL OF HIS COLLEAGUES WITH BAGS OF DEAD CATS'

The 1992 elections were a disaster for Republicans, with Democratic candidate Bill Clinton defeating incumbent President George H.W. Bush, and both the House and Senate remaining firmly in Democratic hands.

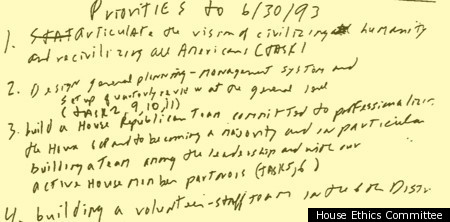

Apparently unfazed, Gingrich pressed on. In December 1992, he reworked his master plan for the GOP during a trip to Florida. The result was a flurry of handwritten notes over three days, which Gingrich believed held the key to a Republican House majority. He gave his project a new name and, with it, a new mission: Renewing American Civilization (RAC).

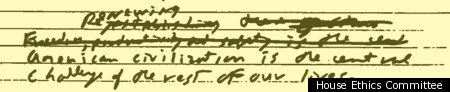

Despite funding pressures, Gingrich during the spring of 1993 was consumed by the idea of turning RAC into a full-blown college course, ready to be broadcast to young people across across the nation. "Renewing American civilization," he wrote, is the greatest challenge of the rest of our lives."

He transferred RAC from GOPAC's offices to a newly created nonprofit think tank that Eisenach founded, the technology-focused Progress and Freedom Foundation.

The move coincided with ALOF's transfer back to Colorado, where it would remain inactive until 1998, when the IRS stripped it of its 501(c)3 status. Before ALOF and GOPAC parted ways, however, IRS records show that GOPAC forgave $43,537 in ALOF debt.

The latest plan was for Gingrich to teach his RAC course at Georgia's Kennesaw State College and for the college to help manage tax-exempt donations to pay for it. There would be a total of 10 lectures a year through the 1995-96 school year.

Not long after the course began, however, Kennesaw State began receiving complaints about the political nature of the material. RAC was soon forced to "find another home," as Gingrich put it in his memoir, and it did, at the smaller, private Reinhardt College.

WATCH a video of one of Gingrich's classes:

Eisenach, who had a Ph.D. in economics, declined to comment for this story, but he testified extensively during the House Ethics Committee's investigation in the mid-1990s into the origins of RAC's funding. Eisenach and other witnesses explained that when RAC left Kennesaw State for Reinhardt, it also lost the donation infrastructure it had with Kennesaw. From that point on, PFF raised the money to pay for Gingrich's course, approximately $450,000 between April 1993 and March 1994, and the same amount between April 1994 and March 1995.

Gingrich decided to shut down the course a year early, however, after the 1994-95 winter term, which ended in March of '95. Later, during the House Ethics Committee probe, he told investigators that he had given it up because he "had learned all he could from teaching the course and had nothing new to say on the topics." Other witnesses interviewed by the committee said the real reason was that Gingrich "had run out of time in light of the fact that he had become speaker" in January 1995.

One former staffer laughed when HuffPost informed him of Gingrich's purported reason for ending the course. "Have you ever heard Newt Gingrich speak?" he asked. "Do you really buy that he had nothing more to say?"

Shutting the course down early left PFF $250,000 in debt, however. When Eisenach asked Gingrich to help raise money -- as he had previously done -- to cover the shortfall, Gingrich, now third in line to the presidency, balked at the notion.

"I was frankly very surprised to learn that you think I have an obligation to raise $250,000 for a project you were in charge of that ran over budget," Gingrich wrote in a scathing note to Eisenach in July 1995, referring to RAC.

"This reminds me precisely of what happened at GOPAC [in 1992] and frankly I find it very disturbing. It is disturbing that you think it is someone else's responsibility to relieve a debt when that person has had no control in the decision-making process. If you take it upon yourself to make a decision you take the responsibility of the debt also," wrote Gingrich.

Documents and testimony from the ethics investigation, however, make it difficult to understand just how Gingrich expected Eisenach to raise a quarter-million dollars for the course without Gingrich, who was its raison d'être.

Moreover, just as RAC promoted Gingrich's philosophy, Gingrich had promoted RAC throughout his myriad political operations, making the two appear practically inseparable to donors.

The symbiotic relationship between Gingrich and his course is captured in a 1993 memo he wrote, which was addressed to "various staffs" of his organizations. Gingrich directs them all to "use the ideas, language and concepts of renewing American civilization at every level, from the national focus of the Whip office to the 6th district of Georgia, [to the] focus of the Congressional office to the national political education efforts of GOPAC and the re-election efforts of FONG [Friends of Newt Gingrich]."

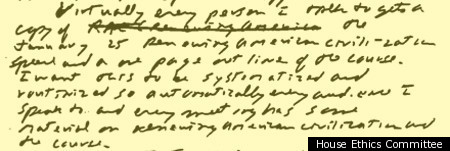

Furthermore, he wrote (above), "I want this to be systematized and routinized so automatically every audience I speak to and every meeting has some material on renewing American civilization and the course."

PFF ultimately paid off the $250,000 of debt for Gingrich's course, according to IRS records, and the group operated independently of Gingrich until 2010.

"Newt leaves all of his colleagues with bags of dead cats," said a former Gingrich colleague when asked about the end of RAC. "Not just one dead cat," he said. "Bags of dead cats."

'IT'S ABOUT GINGRICH'

Gingrich's time at the helm of the House did not last long. Following a poor showing by Republicans in 1998, the speaker faced a mutiny among the younger members of the GOP conference. He resigned from the speakership in late 1998 and the House in early 1999.

"I'm willing to lead, but I'm not willing to preside over people who are cannibals," Gingrich told his colleagues on a conference call. "My only fear would be that if I tried to stay, it would just overshadow whoever my successor is."

Less than a year later, in late 1999, he started up a new political group intent on fundraising: the Committee for New American Leadership (CNAL).

Organizationally, CNAL didn't look much different from Gingrich's last operation or his current presidential campaign. He was at the top as the founder, and Joe Gaylord, his political lieutenant since the late 1980s, was the group's chairman. CNAL's spokesman was Gingrich's former congressional spokesman, Mike Shields, who was also listed as president of one of CNAL's spin-off websites, SocialSecurityPlus.org. Rick Tyler, a former Gingrich 2012 campaign staffer who quit in June and now serves as a senior adviser to the super PAC that is backing Gingrich, was listed as president of another site, Maxtax.org. Both Shields and Gaylord declined to comment for this article.

In addition to Gingrich's people, CNAL also took over more than $100,000 in leftover funds from Friends of Newt Gingrich, which shut down in early 2000, according to a Federal Election Commission report.

Like other Gingrich projects, after a sputter of new websites and lofty goals, CNAL soon disappeared. Its homepage shut down in late 2000. Tyler declined to comment on CNAL's operations except to say that it was dissolved without debts.

For the next six years, Gingrich abandoned his revolving cast of political groups in favor of the private sector, where he made millions as a public speaker, author, consultant and all-around Washington power broker, trading on his experience in Congress. Financially speaking, it was a period of relative calm for Gingrich, who established a nonprofit family foundation during that time but otherwise avoided the temptations of 501(c)3 formation.

In Gingrich's profitable web of private-sector enterprises, all of which seemed to thrive in a way that contrasts sharply with his history of "dot-orgs," Tyler increasingly played an integral role. In 2009, Tyler founded the 501(c)3 nonprofit Renewing American Leadership (ReAL), a group whose mission, according to IRS forms, was "to preserve America's Judeo-Christian heritage." From an address at the Gingrich Group offices in Washington D.C., ReAL in 2010 raised more than $3 million off direct mail appeals, most of which were printed on "Newt Gingrich" letterhead and signed with Gingrich's signature.

Gingrich himself had no official title at ReAL -- the group actually had no full-time employees -- but it did offer him two tangible benefits as he prepared to launch his 2012 presidential bid.

First, it let Gingrich reach potential voters with a pro-Christian message that would eventually dovetail with his campaign. Second, it provided him with the names and addresses of everyone who responded to the donation requests that went out over his signature -- a highly valuable commodity for someone about to appeal for campaign donations.

"For the kinds of people who are responding to direct mail, those are individuals who are going to give because it's Newt Gingrich," said Sunlight's Allison, "and they'll give to anything, whether it's a 527 focused on solutions, a presidential campaign committee or a 501(c)3 focused on leadership. It's about Gingrich. And for Gingrich, the challenge is to find those people."

By the end of 2010, ReAL had a mere $3,404 left of the $3 million. In March 2011, shortly before the group was audited by the state of West Virginia, Tyler left to join Gingrich's presidential campaign.

'IT WAS A SUCCESSFUL VENTURE WHEN GINGRICH WAS HERE'

For his own part, Gingrich founded the 527 political group American Solutions for Winning the Future in 2006 to finance his political comeback. American Solutions raised $50 million in a mere four years, for travel, public speaking engagements, mailings and other expenses, with more than $8 million coming from Adelson, the casino magnate, and his family. Like GOPAC and CNAL, the group was managed by Gaylord.

After Gingrich announced his candidacy for president last year, however, he left the group and took his fundraising prowess with him. Unlike PFF, which survived his departure, American Solutions quickly went bankrupt, having spent $500,000 more in the first half of the year than it took in.

Following the model of so many Gingrich projects before it, American Solutions is now defunct and in legal trouble. This time, however, it's not with the IRS but with the landlord, who sued the group this fall for $19,130 in delinquent rent for office space on Washington's K Street. No one appeared in court on behalf of American Solutions.

According to D.C. Superior Court records, the U.S. Marshals Service was directed to evict American Solutions from the office in late December, but it's unclear whether the order has been carried out.

When asked about the matter, Gingrich's campaign spokesman, R.C.Hammond, said Gingrich had severed all ties with American Solutions in May 2011, so he had nothing to do with its current situation. "It was a successful venture when Gingrich was there," Hammond said. "We are very disappointed that it's no longer successful."

Gingrich still leases space in the building for his other ventures, however, and the willingness of Gingrich and his staff to stand by while an organization he founded and led until last year is hauled into court and evicted for back rent is striking, to say the least.

A spokesman for the landlord, B.G.W. Limited Partnership, declined to comment on the case, as did its attorney. Spokespeople for the U.S. Marshals Service and D.C. Superior Court also declined to comment on the status of the eviction.

Meanwhile, Gingrich's presidential campaign has staggered, soared and plummeted. His win in the South Carolina Republican primary in January was a vindication for the former House speaker, who has dismissed any and all pundits and naysayers who count him out.

That confidence -- however misplaced -- is classic Gingrich and has carried him past all the failed projects that have marked his career, from the fiasco at ALOF in the 1980s through the ethics debacle at GOPAC in the 1990s to the crumbling of American Solutions last year. Despite plunging poll numbers in recent weeks, there are few signs that Gingrich plans to abandon his presidential bid, the latest iteration of his three-decade battle against what he perceives as "the establishment."

Yet bravado alone is unlikely to carry Gingrich all the way to the White House. Even his mega-supporter, Sheldon Adelson, has signaled that he may back another candidate if and when Gingrich no longer seems like a good investment. With expenses mounting, Gingrich's own campaign is poised to become his latest victim.