NEW YORK -- As Rudy Holder walked down East Harlem's main drag, everyone seemed to remember him. One man after another greeted him with a handshake or a quick, one-armed hug. Each exchange brought a nervous look to Holder's face: Friend or foe? Some of the men he recognized. Some he didn't. But they all knew him.

"Trouble," they said, again and again. It was the nickname he'd earned as a teenager.

After serving 12 years in prison, Rudy Holder had come home to East Harlem on parole, joining the 725,000 others who are released from correctional facilities each year across the country. Holder's crime was gunning down two rivals, neither fatally, in 1993. In returning to Harlem, he was hoping to avoid the cycle that engulfs so many ex-convicts and lands them back in jail time after time.

Of the 7 million Americans (1 in 33) who were incarcerated, on probation or parole in 2010, more than 4 in 10 can be expected to return to prison within three years, according to a 2011 study by the Pew Charitable Trusts' Center on the States.

"It's still weird coming back here," said Holder, now a baby-faced 37-year-old, the sun glinting off his shaved head.

A lifetime ago Holder chased little girls in braids and rough-housed with the bigger boys. He spoke with a stutter, which disappeared when he sang, as he often did, with the famed Boys Choir of Harlem. By the age of 10, he was a star drummer at the Pentecostal church where his father was a minister.

In the years to come, the life of a choir boy gave way to fistfights and, later, to gunplay. The unluckiest of his friends wound up dead. Most of the others, Holder included, would end up serving time in prison or on a loop between the city streets and the city jail.

That cycle of repeated arrests and incarcerations comes at a high price to the states, which collectively spend about $52 billion a year on corrections costs. That number has quadrupled over the last 20 years as changing law enforcement philosophies, including the so-called war on drugs, have meant more aggressive policing, criminalization and incarcerations.

But the impact cannot be measured in dollars alone. These ex-offenders, their families and communities suffer not only from the effects of their crimes but also a criminal justice system that is ill-equipped to help them properly re-enter society after they've served their time, advocates claim. Homecomings can be uncomfortable for their victims as well, who often live in the same communities as their victimizers.

Many of these former inmates -- most of whom live in or come from low-income communities -- struggle to find employment, shake addictions and avoid criminal associations. With few job prospects, family pressures and often a lack of marketable skills, many ex-offenders backslide. A large number will be sent back to prison on technicalities, such as breaking curfew or testing positive for alcohol or drugs. Others will commit new crimes.

Former inmates say the stigma of having a criminal record can loom over them for a lifetime.

"Most people come out of prison and they are very energized and they have hope and they are looking to do the right thing," said Glenn E. Martin, a vice president at the Fortune Society, a New York-based organization that helps formerly incarcerated people and their families. "But what they come up against is what is really common for people coming out of prison: lifetime consequences."

In some states, convicts are banned from public housing, said Martin. In others, they are barred from public assistance. And the ubiquity of inexpensive, electronic criminal background checks has made it all too convenient for employers to discriminate, often illegally, against people with criminal records.

"It's really easy to commit crime when you can persuade yourself that no one else out there is convinced of your rehabilitation," said Martin, an ex-offender who served six years in prison. The "tremendous amount of hope" with which people come out of prison is often buoyed, Martin said, "with a tremendous amount of fear of failure."

"There's just enough time to get smacked in the face with, 'I'm out of prison but I'm in this proverbial prison of stigma and all of these other barriers that society has created for me,'" he said. And in some areas the barriers are especially steep.

Holder's East Harlem neighborhood is ground zero for New York City's returning ex-convicts. A seven-block stretch along Lexington Avenue between 119th Street and 126th Street is home to a higher concentration of formerly incarcerated people than anywhere else in the city, according to data compiled by the Justice Mapping Center in New York. An average of about 2,200 men and women return from prison to East Harlem and the surrounding area in Upper Manhattan each year.

This has earned the corridor the epithet, "Convict Alley."

For Holder, the temptations and problems seemed to lurk around every corner, and interactions with those from the bad old days were a test of his will -- and the guidelines of his release. Any association with another convicted felon would be a violation of his parole

In Holder's East Harlem neighborhood, 1 in 20 men has been convicted of a felony, the Justice Mapping Center reported. But in Holder's circle, it's just about everyone, he said, making even the most routine trip through the neighborhood a possible trap door back to prison.

"The street lights had changed, the parks had changed, but still it's the same neighborhood," Holder said with a trace of that childhood stutter. "People going in and out of jail. The same ones are still here and still doing the same things."

This time though, he swore, things would be different.

"I wanted to leave everything else in the past," he said. "I wanted to move forward."

But moving forward would mean steering clear of his old crew and avoiding a long list of enemies that he made in the streets and in prison -- neither of which would be easy in a place like East Harlem, where violence is commonplace and old friends remain linked and loyal to a fault.

He said he'd run into neighborhood acquaintances who would pay for a meal here and there or offer to slide him a little cash. Accepting the money, however, would have come with strings attached, which could pull him back into the street life he once knew.

"They'd say, 'Listen, I see you're still trying to do what you have to do, but we're here, we still need you, you're an OG [original gangster] from the block, come back,'" Holder said. "That temptation was always there in the back of my head. Many nights I stood outside or looked out the window and said, 'Damn, I got $5 in my pocket.'"

There were many sleepless nights, Holder said. "What if I couldn't succeed?" he recalls thinking. "What would be next? Would I go back to my old ways, stick it out or try to find a way to beat the system."

'I WAS THAT TERRORIST, THAT THUG'

While Holder was in prison, a whole generation of ashy-kneed kids from the neighborhood, tough and streetwise, had grown up and taken his place. Some now even had children of their own. A wave of gentrification also had swept through East and Central Harlem, bringing with it refurbished brownstones, higher rent and more white people than he'd ever seen on that side of 110th Street.

And Holder had changed, too. "I went into prison a brash teenager, but I came out a humble man," he said as he walked down 125th Street with his prize fighter's gait.

Growing up, Holder was skinny and shorter than most of the other kids. The son of Barbadian immigrants, he said he dressed differently and had the tinge of some other world in his accent. But the bane of his young life was his stutter. School bullies honed in on the way he clenched his eyes and strained nearly every muscle in his neck and mouth to force out his words.

"I just got mad," he said. "That's where it all started. It turned me into something else."

He got into his first fight at 6 years old and never stopped fighting.

and Maureen Holder in the home that he grew up in that is only a

couple of blocks away from where he committed his crime.

Holder's parents were unaware of the fire burning inside their fifth child. They raised Holder and six siblings in a three-bedroom walk-up. His mother was busy tending to the family and working as a part-time domestic worker. His minister father worked three jobs, including as a cab driver. His parents described him as a "very friendly boy" whose only difference from his siblings was his tendency to stay to himself.

"I was a problem child," Holder recalled. "My mother and father just never believed it."

By the time Holder was a teenager, his anger had blossomed into a rage. He swore to never be picked on again, never to let his size or his stutter make him a target for bullying or ridicule. Holder became a menace, a teenage thug prone to fits of fury that would find their expression in his fists or, when he was older, his guns. Holder won't say how many men he's shot, or whether any of them were killed.

"I just loved the streets and I wanted to build a reputation for myself," he said. "I was that terrorist, that thug, the person that people would tell you to stay away from."

Despite his diminutive size, at 5 feet 4 inches and 125 pounds, he'd often do the dirty work of local thugs, sometimes as a favor, sometimes for pay -- "Depending on what they needed done," Holder said.

He said he reveled in the thrill and power of the violence he served.

As Holder turned up Madison Avenue on a recent sunny afternoon, his stride slowed until he came to a full stop at the corner of 129th Street, alongside an old church whose steeple rose slightly above the brownstones that line the block.

He was eventually charged and convicted of attempted murder and put

Holder stood for a long minute and then walked up to the church and peered down into a dark stairwell that led into the church's basement.

In 1993, during a party in that basement's recreation center, just a block south of his family's apartment, Holder got into a fight with two other teens. As the three of them tussled, a friend slipped Holder a gun. He blasted into the dark corridor, hitting the two young men. A stray bullet hit another partygoer, a female friend who later told investigators that Holder wasn't the shooter.

"It was fear of what I might do to her," he said of the girl's rationale for lying.

Weeks later, a turncoat friend who'd been arrested for an unrelated crime offered Holder up to police for leniency, Holder said.

Holder woke up one morning to find the entire block cordoned off by police cars and a SWAT team at his door, he recalled. He was later convicted of two counts of aggravated assault with a deadly weapon and sentenced to 6 to 18 years.

'MILLION DOLLAR BLOCKS'

While recidivism rates vary from state to state -- California's is about 60 percent, at the high end, as compared to South Carolina's, which is about 32 percent -- the national rate has remained relatively steady over the past decade. According to the most recent figures on recidivism by the Pew Center, the national rate actually decreased slightly from 1999 through 2004, from 45.4 percent to 43.3 percent.

But experts say a host of socio-economic issues make the likelihood of recidivating extremely high.

In the case of East Harlem, also known as El Barrio or Spanish Harlem, analysts blame the area's high incarceration and recidivism rates on the continuing plague of poverty, a concentration of public housing complexes, major disparities in the quality of education and a long history of gangs and drug culture.

Chris Watler, the director of the Harlem Justice Center, a project of the Center for Court Innovation that operates community courts and diversion programs in some of New York City's most at-risk neighborhoods, said that if you follow the trail of corrections dollars, it leads right back to communities most in need of other kinds of funding.

Watler referred to these neighborhoods as "million dollar blocks," a reference to how much money is spent annually on the cyclical incarceration of their residents.

New York spends some $60,076 per year, per inmate, according to recent data.

"These million dollar blocks are not just in East Harlem but in Bedford Stuyvesant, the South Bronx and lots of other urban places in our country," Watler said, adding that these communities also suffer the greatest health, economic, educational and housing disparities. "You begin to see a lot of consistencies in certain neighborhoods, particularly if you were to think about the other areas that the state is not spending money: youth programming, health, other kinds of important things," said Watler.

Back in El Barrio, Holder said that for many in his neighborhood, his experience on the streets was not unique. He was an "enforcer," but other friends were robbing, selling drugs or stealing. Of the eight to 10 guys he said he ran with as a teenager, half have served time in prison or are behind bars today -- the other half are dead. Many go in and out of jail as a matter of routine, he said, a minor consequence to the lifestyle they live.

Early in his sentence, Holder said he was the same old "Trouble" who struck fear in people's hearts back on the streets. While in prison, he got regularly into fist fights and even sliced one man with a smuggled blade. But six years into his sentence, Holder was shaken to his core: an older brother, 27 at the time, died of complications related to AIDS.

"He wrote me a letter that said by the time you get this, I'll be dead," Holder recalled. "It shook my world." Meanwhile, his father became ill and lost the use of his arms and legs.

The emotional hurt was a wakeup call. He knew he had to get home. He had to do better. He had to begin to live.

"I needed a second chance," Holder said.

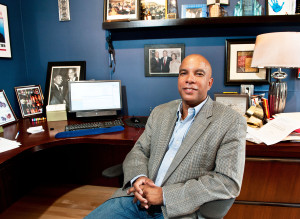

poses for a portrait in the organization's Harlem headquarters.

ROAD TO EXODUS

The first three to six months at home are the most critical in determining whether an ex-offender will relapse, said Julio Medina, the founder of Exodus Transitional Community in East Harlem, an agency that helps newly released convicts re-enter society. Medina himself served 12 years in prison on drug charges, and the agency is staffed almost entirely with formerly incarcerated people.

"We started this 13 years ago with one thing in mind," Medina said during a fundraising event at the Yale Club in Manhattan late last month. "How do we stop people from going back to prison? How do we reduce recidivism? And we've done that."

Exodus uses a holistic approach with the men and women it serves, taking each client's individual history, skills and motivations to tailor programs to each of them and provide them with resources that may best help ex-offenders to avoid relapse. Exodus offers drug, alcohol and anger management classes, as well as job readiness programs.

According to Medina, Exodus has drastically reduced the recidivism rate to well below the national average, and has increased the employment rate among the 400 or so clients it serves to well above the national average.

Of the 356 participants who completed Exodus' program last year, only 9 returned to prison, Medina said. According to the agency's 2011 annual report, about 50 percent of Exodus' clients that year found employment with an average wage of $10.40 an hour.

Over the years, Exodus has served more than 5,000 people, "preventing young people from becoming entangled in the criminal justice system," Medina said. While some will undoubtedly relapse, Medina said "you want to hold on to the victories."

This holistic approach has proven to be a successful model. There are now hundreds of such programs across the country, many funded with state or federal grants, whose aim is to help reduce recidivism. The 2008 Second Chance Act, for example, provided $168 million in grants to organizations that provide employment assistance, substance abuse treatment and other services to ex-offenders.

"When you're talking job readiness, you're not just talking about jobs," said Angel Gavilanes, a workforce development instructor with the Osborne Association, a nonprofit that assists inmates and former inmates. "I think it's very important that you focus on their personal and emotional growth and development, their personalities. Once you're able to shift that, you're able to shift everything else in their life."

Gavilanes knows the men and women better than most. He spent much of his late teen years and 20s wanting to be a "gangster" and drug dealer, and eventually spent more than a year and a half in prison on drug charges before turning his life around.

"You have to adjust their attitude. Either it's a jail mentality or a street mentality. It could be language, it could be a sense of entitlement or resentment for not having what others have," Gavilanes said. "It could be a racial thing. Whatever it is, you have to acknowledge it and work to change it."

During the war on drugs in the 1980s and '90s, the prison population exploded. By 2002, the number of inmates in the U.S. topped two million. America has only about five percent of the world's population but more than a quarter of the total prison population. Minimum mandatory sentences, Rockefeller drug laws and the so-called three strikes policies swept a mass of mostly nonviolent drug offenders into state and federal prisons. Critics and activists accused the war on drugs of being racist by virtue of the population these laws seemed to target, which were mostly poor minorities in inner-city communities. Proponents of the law, however, have maintained that such strategies do not target by race or class, but merely areas in which narcotics and violent crime problems are rampant.

One thing is clear: Most of these convicts will come home, but come home damaged.

"It is a law of diminishing return, where you end up locking up so many black men and men of color, you destabilize that entire community," said Martin, of the Fortune Society.

This destabilization feeds the cycle of recidivism, he said, by fueling a continuous churn of a criminalized class into the system and, in doing so, creates a sort of social dystrophy.

Advocates for ex-offenders and some in the criminal justice field say the holistic approach is a departure from the old paradigm, in which criminals were more or less warehoused until their time was served.

Little attention was given to inmates' personal and emotional needs, said Dora B. Schriro, commissioner of the New York City Department of Corrections, the second-largest jail system in the country. She said they would be released no better than when they went in -- and as likely to return.

The average inmate on Riker's Island has had 11 prior stays at the jail, according to the DOC. These inmates are basically serving a life sentence "on an installment plan," Schriro said.

"At the end of the day, whether a person does a lot of time in a corrections facility or just a short time, sooner or later everyone is released and they come back to the streets," she said. "How do you want them? The same as they were, worse off or better?"

Schriro, a former director of the Arizona and Missouri departments of correction, said that when she came to New York City, she wanted to take a new approach to dealing with the inmates on Riker's Island.

She said that re-entry preparation in many correctional facilities is back-loaded with programs that begin a year or so before an inmate is to be released. Aggressive programing must start on day one, Schriro insisted, explaining that what is needed is "a system of objective or science-based assessment instruments to best determine the risk of return and needs of each individual that comes into the jail."

In the past, she said, a self-evaluation was taken and a uniform set of programs might have been offered. But along the way, gauging an inmate's needs incorrectly or misdirecting resources created opportunities for failure that could be avoided by delivering a wider variety of programs in a more progressive and intuitive manner.

Schriro implemented a new philosophy at Riker's. During an inmate's time in jail, he or she no longer is simply told when to wake up, when to move or when to report to a specific place. Clocks have been installed throughout the jail, she said, forcing inmates to be more responsible and plan their schedules.

Within the first 10 days of an inmate's arrival, a trained counselor conducts an assessment of employment history, addictions, health status, and level of education, and then provides any help the inmate might need to secure legal documents, such as a Social Security card or birth certificate.

"That way, we can really figure out if you have a high level of need and a high likelihood of being re-arrested. Those are your 'hot damn people,' the people you really want to offer every opportunity to use their time in detention to prepare for release," Schriro said.

While Schriro is encouraged by what she sees as the qualitative improvements in prison life among the inmates and guards, no data has yet quantified the effectiveness of the program on reducing recidivism.

'RUDY'S BACK'

Rudy Holder has been back in East Harlem for almost 10 years now. And nearly six days a week, he is out on the streets. But this time around, he's not looking for trouble. He is looking to keep others out of it.

Just days after his release from prison, Holder walked through Exodus' doors and never left. He started out as a client, became a volunteer, then an intern and eventually a full-time employee.

"I kept seeing this guy hanging around on the computer; every single day, there he was," Medina, Exodus' founder recalled of Holder. "One day I asked him to see his resume, and at the top of it he had 'Public Speaker.' I said, 'Okay, let me hear something.' Then I hear the stutter, and I said, 'You have got to be kidding me!'"

"He's been here with me ever since," Medina said. "We call him our bounty hunter."

Holder's official title is retention specialist.

When new clients, particularly those with a high risk of recidivating, start missing meetings and classes, Holder goes looking for them -- to their old hangouts, their last known addresses, "he'll sit on your mother's step just waiting for you," Medina said, as the two of them stood in the middle of Exodus' offices on East 3rd Avenue. "He'll do what he can to get you back."

"And I find them all," Holder said, breaking into a wide, toothy grin.

"This is my calling, my ministry," Holder said. "As Mr. Medina says, we are wounded healers. I live this and breathe this -- it's not for a pay stub."

Holder knows his clients well. "I was one of them," he said. So he does his best to be less a parole officer and more like a straight-shooting friend or uncle.

"I get to tell my personal story. And most of them either heard of me or knew me from the streets or in jail, and they can see the change in me."

Holder said he has not been re-arrested since he left prison all those years ago. He credits Exodus, which he calls "my second family" for much of his success.

But his role at Exodus hasn't been without incident. His reputation has preceded him, and on a few occasions people from his past, including some with whom he's had beef or even fought in prison, have showed up as clients. One day, a gang member who had problems with Holder found himself on the wrong side of a left hook and ended up sprawled across the Exodus floor. Another time, Holder said he came face to face with a man he'd cut with a blade in prison. "I had to just look him in the eye and tell him that I'm not the same person that I was," Holder said.

Holder now lives in Connecticut with his girlfriend and makes the daily commute back to East Harlem five or six days a week. Most days he's on the train by 4:30 a.m. Sometimes, when his caseload is particularly heavy, he'll sleep on a couch at the office.

Holder has returned to church and plays the drums in a number of church bands. And, coming full circle, he also volunteers at the church where the shooting occurred. "It's a great change," his father, the Rev. Jeffrey Holder says. "With God's help," his mother, Maureen, chimed in.

On that long walk back to 129th Street and Madison Avenue, where years earlier Holder was known and feared, his eyes and smile lit up as a tall, burly man standing by a payphone called out his name. The man didn't call him "Trouble," he called him, "Mr. Holder."

They smiled and exchanged a bear hug that nearly swallowed up Holder.

The bigger man was Timothy Brown, Holder's very first client at Exodus.

"He helped me to get back on my feet, back into society," Brown, 45, said, beaming down at Holder. "He stayed positive, and I just wanted what he had."

Brown is now married with three children and works as a cook. Holder was the best man at his wedding.

"I'm giving back. And I say that with great pride," Holder said. "To see the transformation in them, it's like they can see that if I can do it, they know that they can do it, too."