NEW YORK -- Ana Enriquez, 17, did her homework in a rat-infested South Bronx apartment, where she shared a bed with her mother and lived with five other relatives. She once considered a career selling drugs. Now she studies how they affect the brain and dreams of winning a Nobel Prize.

Janell, also 17, watched former classmates from her tough Washington Heights neighborhood drop out of school and go to jail. But she plans to make a life on the other side of the prison bars, working as a forensic psychologist for the FBI.

Julian, 16, lives in the Bronx projects, where he sleeps in the living room, taking turns with his brother on the couch or the floor. He has also seen people abuse drugs and commit crimes -- and, like Janell and Ana, he's drawn inspiration from those experiences. He wants to start a nonprofit that helps poor kids; but in attending a school that he feels is callous to his troubles at home, he worries about his chances for success.

"I feel like I'm not ever going to make it out of here," he said. "Like I'm not going to college."

Julian, Ana and Janell started high school at about the same time in impoverished New York neighborhoods, but each took a different turn as they journeyed through the public education system.

Julian attends a traditional public high school that relies on often beleaguered and overworked teachers and standardized testing to educate students. Ana is enrolled in what has become a showplace for the "No Excuses" approach to teaching, which favors heavy discipline, charter schools and linking teacher evaluations to student test scores. By contrast, the Salome Ureña de Henriquez campus where Janell studies has adopted what's now called the "Broader Bolder Approach," which contends that poor students need to be surrounded by an array of services -- from adequate nutrition to health care and counseling -- before real learning can take place.

All three students are up against the same challenges that thousands of other low-income kids face every day: Economic and social forces that routinely conspire against their chances of acquiring that most basic building block of success in the United States -- an education. Their situations are emblematic of a fierce, ongoing debate about how best to close the yawning gap that exists between the test scores of rich and poor kids.

These approaches sometimes overlap: No Excuses proponents believe that poverty can affect learning, and Broader Bolder proponents espouse the importance of good teachers. But politics and history forced these two groups to develop separately, and in a post-recession era, the limited availability of philanthropic and government funds often has them at each other's throats. Ultimately, if a school had $1,000 to spend, Broader Bolder advocates would likely put it toward a clinic or a social worker; No Excuses supporters would probably spend the money on recruiting a teacher whose students boast more impressive test scores.

The stakes are high. Almost one-fifth of America's school-age children live below the poverty line, and the achievement gap is growing. While proponents of both philosophies trumpet their respective success stories, there has been little in the way of conclusive data to prove which approach will do a better job of closing that gap.

No Excuses advocates point to high-performing charter school networks like the nationwide Knowledge Is Power Program: Thirty-three percent of KIPP students graduate from college, far higher than the norm for students from low-income backgrounds. But Broader Bolder proponents say schools such as KIPP succeed because they get more money, not because of a fundamental difference in how they educate students. Broader Bolder advocates also counter with studies such as one that the City University of New York conducted that showed an increase in the attendance and test scores of students in Broader Bolder "Community Schools."

The few objective analysts who have studied the two approaches largely agree that, while each could benefit from a little dose of the other, those kids without a lifeline to either face a much tougher road.

Ana and Janell are both relying on these lifelines. No Excuses spawned Democracy Prep, the Harlem charter school where Ana is focusing on biology. Janell, meanwhile, has blossomed under the Broader Bolder approach. But Julian, once an honors student, remains stuck in the cracks of New York's public school system.

Julian: Status Quo

Julian missed three days of school last semester when his mother was evicted. She couldn't afford movers or a U-Haul, so he spent those days helping her carry bags and boxes across the Bronx to their new home in his grandmother's apartment in the projects. During the move, Julian says, his English teacher brushed off his requests for make-up work. When Julian failed the class, she responded to his pleas with a sarcastic "Good luck." It's hard to know why that might have happened, if it did, but the story was one of many he told that seemed to paint a bigger picture.

After a truck hit Julian's math teacher, he says, a substitute took over for the rest of the year. The new teacher seemed to spend more time discussing boxing than math. "Obviously, substitute teachers aren't real," says Julian. "My neighbor was once my substitute teacher. I don't think he spoke any English."

Today, Julian shares his grandmother's living room with three siblings and his mother. Julian's father is out of the picture and provides no child support, but Julian doesn't like to talk about why. He goes to school in the South Bronx, an area that remains one of the poorest in the country, even 30 years after President Jimmy Carter visited the burned-out borough and declared it one of the most sobering examples of the country's "rapid deterioration." The school's facade is new and brightly colored, offering a counterpoint to the abandoned churches and tire shops that surround it. Next door is a building encircled by barbed wire -- a day-care center.

So, why is it hard to teach poor kids like Julian? That's the central question in a debate that will likely shape the future of American public education.

Its roots date back to the early 1990s, when a lawyer named Sandy Kress began looking at standardized test scores in Dallas and found a troubling trend. For decades, the scores of the city's minority and low-income students had been going up. But in the late 1980s, they began to level off. Kress, a former member of Carter's Treasury Department, proposed a solution based on business principles: A school's performance on standardized tests should determine whether teachers get cash or get fired.

Kress' proposal sparked a battle among Dallas educators, but the idea spread. By the time George W. Bush became president, a bipartisan consensus had formed around school accountability, a concept that would become the federal No Child Left Behind law. While the term "accountability" may be ubiquitous in modern education law, it was novel at the time. Governments across the country gave schools money without demanding equity or excellence in return.

Julian got neither equity nor excellence: He didn't have the tools to learn, and he didn't get teachers who helped him excel. One recent weekday, a school librarian snuck a reporter past the security guard at the front desk. Most public schools don't like the media to write about their problems, so it can be hard to arrange an official visit. Julian requested that his last name be omitted from this article and that his school remain unidentified, for fear of retribution against himself and his family. "People don't like us here," he says.

Julian sits in the library, where he often spends his lunch period, helping the librarian check out books for other kids. He's a quiet, reserved 16-year-old, but when he talks about why he likes to spend his time with books, he says things that are more true of life in neighborhoods like the South Bronx than in places where the day-care centers don't have barbed wire around them. "It's a dog-eat-dog world," he says.

"I only got robbed once," he adds, describing the time when "some dude" stole his little sister's game console straight out of his hands outside the school.

For the next hour, Julian details how the school isn't meeting his needs, academically and otherwise. While Julian is quick to accept blame for not working as hard as he thinks he should, he's also frustrated by the things he can't control. One day last year, Julian walked into the library, crying. He'd been kicked out of class because his shoes were the wrong color, according to the dress code. They happened to be the last shoes available at his homeless shelter, and they were a size too big. But his teacher, unaware of his financial situation, gave him detention. This became a pattern, since detentions didn't change the fact that Julian still couldn't afford new shoes. One detention became 20, and the time away from class meant Julian was learning less. "It doesn't matter what you wear, what color your shoes are," he says. "That's not going to hinder your education."

Julian's school is precisely the type of program Kress wanted to fix. After Julian started high school, he was accepted into a special honors program. He came to school every day with a smile and always finished his homework, recalled Nicole, a former history teacher who left the school and called him "brilliant." Julian started his junior year looking forward to college. But the material quickly got tougher, and his school didn't do much to prepare students for that reality.

Things at home have gotten steadily harder, too. When Julian's mother, a school aide, was evicted and had to move in with his grandmother, Julian became so depressed, he almost stopped sleeping. And this was not the first time he and his family had been evicted. They had been evicted from their previous apartment a year earlier, and Julian went to live in a homeless shelter.

Julian is so ashamed of his transitory life that he refuses even to acknowledge that chapter. He does, however, talk about moving into the projects this year with his grandmother. "When I moved in, I was scared I was going to get shot," he said. "I don't sleep so much because it's so loud."

Julian's troubles mirror the concerns some experts had before Bush made Kress' accountability policy the law of the land. A civil rights coalition, Opportunity to Learn, argued in the '90s that accountability stressed excellence while ignoring the system's inherent unfairness to poor and minority kids. Before you can increase expectations, they said, make sure kids are prepared to learn.

But the group had little involvement in the negotiations that turned accountability into No Child Left Behind, which mandated testing of all students in English and math and imposed a series of consequences based on those results. The idea was, if schools and teachers were held accountable for their failures, things would get better, especially for poor kids.

Ten years after its passage, No Child Left Behind's flaws are clear even to its original cheerleaders. Clauses that required free tutoring for underperforming schools spawned fly-by-night tutoring companies, and funds designated to help poorer schools ended up in the coffers of some wealthier schools. Critics also say the law forced schools to narrow their academic focus to the subjects of state tests, to the exclusion of most everything else. "The push is away from everything non-academic," said the librarian at Julian's school.

In January, Julian started to struggle academically. He failed out of his honors courses in science, English and math. Once Julian fell into regular classes, he noticed his teachers cared less. While that lack of concern is Julian's perception, it's one that is shared by his former teacher, Nicole. Regular students, she says, are "completely ignored."

"Some teachers weren't explaining anything to me," says Julian. "That's why I'm in the predicament I'm in now." That's why he's not sure he'll graduate, and that's why he is not as optimistic about his prospects as Ana and Janell are about theirs.

Every day, Julian stares out the window of a city bus on the way to school, a commute that can sometimes be a gauntlet of terror. Once, Julian witnessed a loud argument in which one of the participants pulled out a gun. He thought he was going to be killed. He got out of the path of danger, pondering his mortality.

He says, "I'm either going to die from disease or saving somebody."

Ana: Tough Discipline

It's because of problems with schools like Julian's that Democracy Preparatory Charter High School, where Ana studies, came to exist.

For a few months last year, Ana was locked away in juvenile detention on Staten Island in what is called a "diagnostic-reception center." It may as well have been called "jail school." By Ana's account, fights constantly broke out around her.

The jail school was a far cry from Democracy Prep, a top-performing and quickly improving New York City school. Following years of Ana's misbehavior, her principal recommended that she attend. Ana had never heard of a charter school but figured she might as well give it a try. Her expectations weren't particularly high, and indeed, it took awhile for her to show signs of progress. For the first few years, she ditched classes, she cut herself, and she once ran away for two weeks. There was a period when she stayed out so late that her mother asked a detective to arrest her.

But Ana wasn't just any wayward kid. She was a wayward kid who had to contend with the frustrations and deprivations of poverty. She says she wore hand-me-downs until she turned 14, lived on a corner that Ana calls "prestigious" among prostitutes, and coped with a mother who constantly threatened to send her back to tribal Mexico. "There was a whole bunch of rats, bad hygiene," she says. As an undocumented immigrant from Mexico, Ana says she grew up in constant fear that her legal status would leave her with few career possibilities other than cleaning apartments, like her mother, or selling drugs.

The turning point came on a November day a year and a half ago. Ana came home from one of her late-night bashes to find two cops in the stairwell of her apartment. Her mother had asked them to come, and Ana soon found herself in the detention center.

At "jail school," she suffered through mind-numbing math classes for kids who'd barely learned arithmetic. Compared with her new school, Democracy Prep suddenly seemed like an exciting challenge. When she finally returned to the charter school, she started participating in classes, raising her average to an 87 and developing an interest in biology.

"I'm not a religious person," she says. "I don't believe that God created us. I don't know exactly what to believe, but that's the beauty of science. You can prove these things. There are so many things out there that want to be discovered." She's now a high school junior, and dreams of enrolling in college, getting a Ph.D. and, just maybe, one day, becoming Mexico's first female president.

Ana and her peers have such opportunities thanks to Seth Andrew, a lanky 35-year-old Brown University graduate who founded Democracy Prep. Andrew, who spices up his business suits with a yellow baseball cap, speaks at a rapid-fire clip, and when he talks about his ideas, he sounds like an excited boy showing off a new toy. "There's no amount of challenge, no family situation that will let us say, when a kid walks in this door, that we're not going to get them to that goal of college," he says.

Andrew is one of several policymakers and academics who consider themselves champions of the No Excuses model, a group that thinks No Child Left Behind didn't take accountability far enough.

Apart from Andrew, one of the biggest advocates of the No Excuses approach is New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg. He took the idea for its first real test-drive in 2002, when he appointed a lawyer named Joel Klein to lead the nation's largest school system. As Klein saw it, that system had become a morass of patronage, corruption and incompetence. Klein developed the tenet that would fuel the growth of the No Excuses movement. Some educators, he thought, used poverty as an excuse for failing to ensure the success of low-income students. "America will never fix education until it first fixes poverty -- or so the argument goes," Klein wrote. "The truth is that America will never fix poverty until it fixes its urban schools."

Klein went into battle mode, launching a successful effort to increase the number of charter schools allowed by the state. Charter schools, a key weapon in the No Excuses arsenal, are semi-private entities that can hire and fire teachers as they please. Their managers often borrow concepts from the corporate world. No Excuses founders wanted to clear away the red tape of government regulation and work around the union's rules so that they could hire better teachers, make them work longer hours, and compel their workforce to conform to heightened expectations of performance and productivity.

No Excuses hinges on the notion that the best way to lift children out of poverty through school is to have effective teachers concentrate almost exclusively on boosting academic performance. Advocates point to a 2011 Harvard study that found that top-tier teachers can impart three times as much learning as the weakest teachers, raising a classroom's lifetime earnings by $226,000.

Still other research has found that differences in student achievement can be explained mostly by socioeconomic backgrounds. One study found that while teacher quality is indeed the most important academic factor in determining student performance, it only accounts for about 8.5 percent.

Still, Klein's agenda attracted a wide range of backers, from Hollywood conservatives to East Coast liberal hedge funders. It also appealed to a state senator from Illinois named Barack Obama. When he became president, Obama placed a provision into the 2009 stimulus bill that encouraged states to increase the number of charter schools. Touting a viable sea-change approach to education, No Excuses backers courted philanthropists and launched grassroots movements to raise money. They have since spent millions on lobbying and consultants to push their agenda. Bloomberg himself appeared at a recent fundraiser for Ana's school, Democracy Prep.

Andrew, the school's founder, says he thinks the school can lift students out of poverty by hiring good teachers and showing them that they can do better than their parents. In a recent interview, he noted that the school stands only blocks away from the campus of Columbia University. "None of our students had ever set foot on it," he said. "That is the reality of a very small, narrow worldview that we try to expand rapidly when our kids walk in the door." He said by the time they graduate, they will have gone on school trips to at least 100 colleges.

Democracy Prep has four campuses in Harlem, and will open two more this fall. As students walk its halls, they pass inspirational quotes from celebrities who grew up in tough neighborhoods. They wear uniforms emblazoned with the school's crest. Classrooms are named after universities, so they might walk from Columbia to Howard. Outside one classroom, a document lists the names of students who failed to turn in their homework. Everywhere there are reminders of the school's focus on hard work, high expectations and discipline. And there are a lot of rules. You need to walk in a straight line between classes, you must sit up straight and make eye contact with your teacher -- and if you fail to do these things, you're likely to get detention.

Ana is an enthusiastic backer of Democracy Prep, though she and her friend Meliza share doubts over Democracy Prep's strict discipline policies. Having half the students in detention on any given day because of minor infractions, they say, is not only overly harsh -- it's ineffective. Detention is more like a group hangout.

But Democracy Prep's advocates believe their No Excuses ideas are paying off. They note that 92 percent of the school's students passed the citywide math exam last year and its students are improving on tests faster than their peers.

While some research shows that charter schools, on average, perform at the same levels as traditional public schools (with some exceptions), critics contend that some perform better simply because they receive more philanthropic money. To help all low-income students, these critics say, schools must provide "wrap-around" services that ensure there are no outside distractions to take a student's attention away from the classroom. That's the Broader Bolder Approach.

Broader Bolder advocates say schools must provide students with access to social services to relieve them of the disadvantages of being poor. And as it happens, Ana, the No Excuses poster child herself, attributes her success not just to the rigors of Democracy Prep but also, and especially, to a fortuitous encounter with a social worker.

When Ana was locked up in the detention center, a social worker introduced her to a lawyer, who presented Ana with a plan for becoming a citizen. The meeting filled Ana with hope, and it motivated her to start behaving better. It was only then, she says, that she was able to return to Democracy Prep. "If I hadn't had my epiphany," she says, referring to the meeting, "I probably would have been the same person I was before I got locked up."

Janell: Support and Services

It's hard to know exactly when the Broader Bolder Approach took hold. The idea that poor kids need a lot of help may seem obvious, and plenty of scholars have been advocating it for a long time. Schools first began to adopt it under the aegis of the Broader Bolder Approach in 2008, when a researcher named Richard Rothstein convened like-minded academics to write a manifesto called "A Broader, Bolder Approach To Education." In this seminal essay, they argued against the assumption that "school improvement strategies by themselves can close these gaps" and urged educators to regard their work as the "development of the whole person, including physical health, character, social development, and non-academic skills."

Janell's school, part of the Salome Ureña de Henriquez Campus, takes these principles very, very seriously.

On a recent school day, Janell sat in a teachers' lounge in the basement of the building and gushed about her school. In addition to her gray school T-shirt, she wore bright blue nail polish and a long-fringed charm necklace, which she twisted playfully in her hands. She was in the middle of her shift as a tutor for the school's after-school program, and outside the door, in the cafeteria, groups of younger students sat around doing homework while her fellow tutors hovered over them. At one point, a younger student tried to jam a dollar bill into a decrepit soda machine. In the authoritative manner of the FBI agent she hopes to become, she reminded him that the school forbids students from drinking soda during tutoring hours. "You're not allowed to do this," she said. After a second attempt and a second scolding, he shuffled out of the room with his head down.

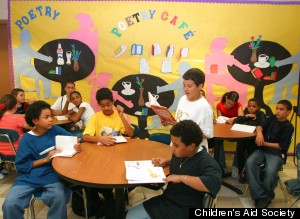

The lunchroom looks like any other school cafeteria, but up a flight of steps, a hallway leads into a "family room" with computers and couches, where students' parents can take classes in computer literacy or get help with their resumés over a cup of hot tea. There are actually three schools in the building -- all of them run in collaboration with the Children's Aid Society. On a typical day, students take classes and meet with tutors, and when the situation calls for it, they can also pay a visit to a social worker, a dentist, an orthodontist, a college counselor or someone called a "community coordinator," who is tasked with making sure all teachers and specialists work in concert, providing the students with wrap-around services.

The availability of these services is what defines the Broader Bolder Approach, and Janell attests that one of these programs helped change the course of her life. When she began going to the school in the ninth grade, a tutor helped her catch up on the material she'd been unable to grasp. She did so well that the school asked her to become a tutor herself. Now she's getting paid. The belief is that a student with money will have less stress and do better in school.

Ideas like that caused Rothstein, a researcher at the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute, to rally scholars in 2007 as No Child Left Behind expired. Congress was preparing to rewrite it (a task they've still not completed), and Rothstein wanted to persuade legislators that the Bush version fell short by not ensuring that poor students have the resources they need to learn. Over 60 respected education figures signed a petition in support of this argument, among them New York University scholar Pedro Noguera, who advises urban school districts like Newark, and Linda Darling-Hammond, a Stanford professor who advised Obama's transition team. One day later, a group led by Klein issued its own manifesto.

Broader Bolder bolsters its argument with research, including a recent Brookings study that found that every additional $10,000 increase in annual parental income provides the equivalent of slightly more than one month of learning.

Fifteen years before Broader Bolder bubbled up in academia, Children's Aid built the Ureña campus, a three-story building on Broadway and 196th Street in Washington Heights. The area retains pockets of deep poverty and crime even after a wave of gentrification. Growing up in the neighborhood, Janell often learned about the gunshots second-hand, through her friends. "My mother put her hands over my ears when the bullets were flying," she says. "My friends would be telling me, 'Oh, this and that shooting happened,' and I didn't even know. That freaked me out."

When Janell started at the Children's Aid school, she felt lonely. Her old friends hung out in the park every night. They'd call to invite her, but she could never join -- the tutoring sessions kept her in the building well into the evening. "Without this school, without Children's Aid," she says, "I might be pregnant now."

Janell may be among the school's last students to benefit from all of its services. Broader Bolder methods are expensive, and for the first time, the city is making Children's Aid at Ureña pay for facilities and security, at the cost of an additional $30,000 to $50,000 every 10 months. Its summer programming is on the chopping block.

As Migdalia Torres, the Ureña campus community director, put it: "We've got no money."

***

Back in his school's library, Julian describes his dreams. If he were building a school from the ground up, it would resemble a hybrid between Ureña and Democracy Prep, with the kinds of qualities researchers say work best together. First of all, the building would be clean: No more rats or overflowing toilets. Then, he says, he'd interview teachers very, very carefully. They'd have to know a lot about their subject areas and have the ability to make students succeed; but more importantly, they'd have to care about everyone. They'd have to pay special attention to the students in the toughest situations.

Richard Buery, a Harvard graduate from East New York who leads the Children's Aid Society, is building that school. Since Children's Aid schools can't hire their own teachers, Buery plans to open the organization's first charter school this August. The school's admissions lottery will favor the homeless, poor and orphaned. It will hire teachers who can boost students' test scores and surround that academic core with health care and social services. The school might determine success not only by students' academic performance, but also by their body mass index.

While No Excuses and Broader Bolder publicly fight, Ana practices for the SATs. Janell is preparing to attend John Jay College next year. They both anticipate leading better lives than their parents. But Julian is still struggling, still missing classes because he's not wearing clothes he can't afford.