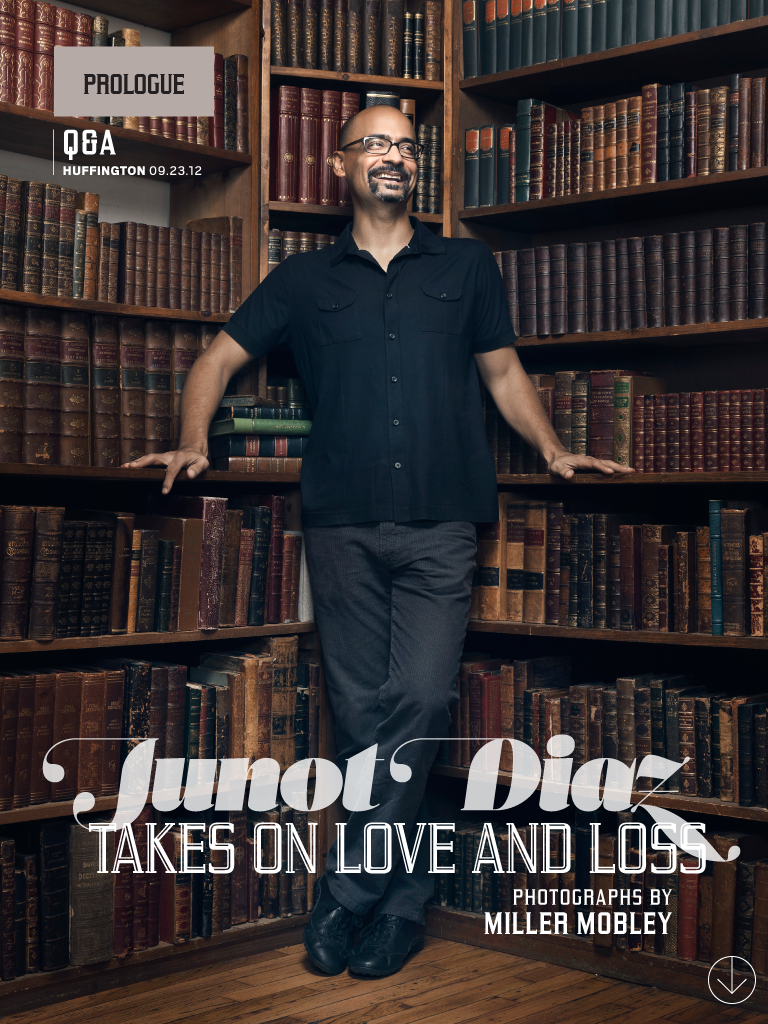

Like great writers before him, Junot Diaz can’t leave himself off the page. In his three works — Drown, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, and his new book, This Is How You Lose Her — Yunior, Diaz’s literary alter ego, looms large. We first encounter Yunior in the short story collection Drown as a young adolescent torn between the projects of New Jersey and the open campos of the Dominican Republic. In Oscar Wao — the novel for which Diaz won the Pulitzer — Yunior takes a backseat to tell the life of Oscar, a science fiction-obsessed would-be writer trying to unearth his family’s history and get laid. Returning to the short story in his new collection, This Is How You Lose Her, Diaz turns his focus on Yunior, excavating the narrator’s early adulthood relationships, littered with loss and love. Yunior’s story gives voice to Diaz’s explorations of his own youth — as he puts it, those years are “the well I always seem to draw from.” --Nicholas Miriello

David Long has said, “Novels are mostly middle; stories are all beginnings and endings.” Do you agree with his analysis?

Any answer about forms so diverse will always be necessarily incomplete. Whatever I say about the novel or the short story is more about my own aesthetic than it is about novels or short stories per se. With that said: My sense has always been that the novel traditionally is better at conjuring a world than a short story. Part of what gives many of the novels I’ve read their immense power is the way they are able to immerse readers into the world of its characters. Not only the time-space, the characters, but the worldview, the sensibility, the historical and material and social moment. In the novels I’m most familiar with, a reader literally leaves their world behind in order to inhabit this new world which the writer has drawn up. There is something demiurgic about novel-writing. Stories can do worlds well too — one only has to recall Octavia Butler’s short fiction — but in general a world is best made real, made credible, over the long span than the short. Fictional worlds flow best, live best, when a book has built up a relationship with its reader. Stories, on the other hand, gain their power from their very brevity. While a short story cannot build the same kind of relationship with a reader that the novel can, the short story can far more convincingly remind the reader of life’s cruel brevity and of how irrevocable some of the shit we decide and that happens to us can be.

In your experience, how do you negotiate the demands of writing in these different structures?

For me, novel-writing is all about coping with the form’s utter imperfectability. Short-story-writing, on the other hand, is all about coping with the form’s vexing perfectibility.

In This Is How You Lose Her we follow the character Yunior in fragments, constantly returning to his familial relationships and the close quarters of London Terrace. What about Yunior, Rafa and New Jersey keep you coming back?

Stories about less-than-brotherly brothers are one of those timeless formulas in our culture which, for some of us, have unlimited appeal. But more to the point, if Conrad has the river in the Congo, I have my teenage years in London Terrace, wrestling first with my brother’s craziness and then with his cancer. It’s my foundational narrative chronotope, the well I always seem to draw from. In this moment where, for better or worse, a huge part of who I would become was made. I still don’t really understand all that happened in those years, and I think part of my compulsive returning to that time is the predictable desire to comprehend. As an artist, if your internal space asks you to draw boats, you draw boats — nothing you can do once that call arrives. With me, I find myself called upon again and again to return to those years and [there’s] really nothing I can do about it.

John Updike once said, “I have written in the first person. In the end it becomes a kind of trap, one wouldn’t want to call the masterpieces of first-person fiction monologues, but there is that danger always of never getting outside that one voice and that one head.” As someone who uses the first person masterfully, do you sense that “danger” when writing so closely to one voice and, in the case of Yunior, with one character for a long period of time?

Each narrative mode has its benefits and its dangers. Third person, for example, runs the risk always of being dreadfully etiolated and sounding like it’s been dipped for a decade in an acid bath made up of the pulped voices of 1,001 old dead white males. Third person runs the risk always of being something that doesn’t dance. And first person clearly is always in danger of becoming a narcissistic pinhole, an all-or-nothing bargain. But again, I don’t think one writer’s preference says much about what is possible in the form. One thinks of the grandeur of Ellison’s Invisible Man, first person, and the mad intelligence of Nabokov’s Lolita, and also of the brainy, frenetic insouciance of Stephenson’s Snow Crash, third person, and it becomes clear that neither first nor third has any monopoly on greatness, on piercing our bifrost hearts. When one considers how third person in some Victorian novels was little more than a masked first person — with the third-person persona even addressing the Dear Reader — one is reminded that the two modes have a lot more in common than one might think. Ultimately the power of a narrative mode derives not from some theoretical default setting but from how its practitioner deploys it.

What are you reading now?

Percival Everett’s classic Erasure and Diana Thung’s amazing graphic novel August Moon. I’m definitely one of those writers who doesn’t stop reading ever, not even when I’m writing. Shit, when I’m writing, I read even more.

This story originally appeared in Huffington, in the iTunes App store.