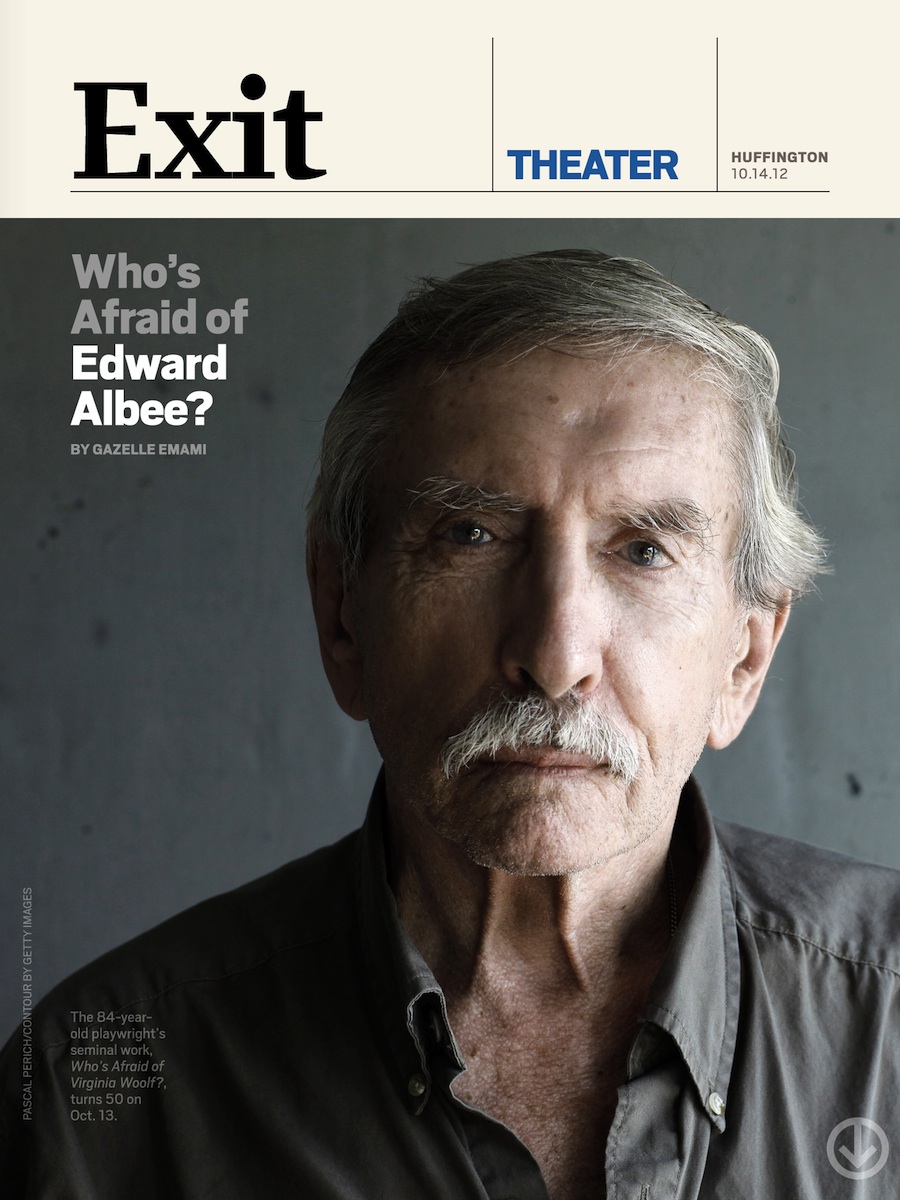

EDWARD ALBEE, 84, inches his way through his apartment by cane, settling into one of many leather chairs that fill the Tribeca loft with its overwhelming scent. Talk to him, and he will run circles around you. Prickly and quarrelsome, you’d think Albee were out for blood if it weren’t for a mischievous gleam in his eyes, and the occasional, almost imperceptible, wink. “I hope I haven’t been difficult,” Albee said, as we ended. “I’m just having a little fun.”

If Albee is difficult, it’s only in the challenge he presents: to speak and engage thoughtfully with those around you; to be alive in your language. The author of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? — celebrating its 50th anniversary on Saturday — is regularly referred to as one of the great American playwrights for his scathing examinations of the human condition, often punctuated by sadism, aggression and weakness. Albee carves his way through The Zoo Story, A Delicate Balance, Three Tall Women and some 25 other plays with razor-sharp dialogue.

“A playwright... is his work,” the three-time Pulitzer Prize-winner said last year, and Albee lives by this maxim, demanding the same level of acuity in his conversation as he does in his writing. “Always be specific,” he recommends, generally. He has reason to belabor this point. As a playwright, Albee’s work is fully realized when it reaches the stage, at which point misinterpretation becomes a real possibility. (It’s always a possibility, but for other reasons, Albee says: “Some people have written that it’s hard to understand my work, but they’re not very intelligent. If you’re stupid you will misunderstand what I’m saying.”)

He’s advised young playwrights to write “so precisely that [the actors and directors] really have to be creative to go away from the author’s intentions.” Take one direction he wrote for a character in A Delicate Balance: “Speaks usually softly, with a tiny hint of a smile on her face: not sardonic, not sad... wistful, maybe.”

“I’m not one of these playwrights who thinks directors and actors should have free rein to do whatever they want to do,” Albee says. “If they want to do what they want to do, they should write their own plays.”

When a play has on occasion escaped his control, Albee’s solution is simple: never work with that director again. “And I discourage other people from working with them,” he adds.

Albee’s most popular and critically acclaimed work to-date, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, has had many occasions to be misread over the years. The play, which was first staged at the Billy Rose Theatre in New York when Albee was 34, took him from well-regarded off-Broadway playwright to household name and Tony Award-winner. His three Pulitzer Prize wins notably do not include Woolf (while it was in contention, the committee decided to give no drama award that year).

On Oct. 13, a revival of the play — which first ran at Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theater — will open on Broadway for the fourth time at the Booth Theater, 50 years to the date of its premiere. As is usually the case with a major production, Albee chose the director (Pam MacKinnon), the cast, the writers, and no changes to the text were made without his permission.

“It’s quite good,” Albee says, in a a rare show of approval. “I think you’ll like it.”

Woolf’s plot rests in the deeply comedic, deeply sad barbs George and Martha — a professor and his wife, the daughter of the university’s dean — throw at one another while hosting a new, younger professor and his wife, Nick and Honey, for a boozy, 2 a.m. nightcap. “Braying” Martha and George, the “cluck,” as they affectionately call one another, engage in a series of ugly “games” aimed right where it most wounds the other, eventually pulling their guests into the fray (the game: “get the guests”). This, in a time when America’s idea of a marriage drama was The Dick Van Dyke Show.

Over the years, productions of Woolf have struggled to hit the play’s sweet spot, between the intellectual and the emotional, or the “mind and the gut,” as Albee has put it. He told Rakesh H. Solomon, author of Albee in Performance, that the first, Tony Award-winning Broadway production in 1962 skewed a little too emotional. But it’s the most widely-known version of Woolf that’s strayed furthest — the 1966 film starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, who were two years married at the time. Soon after its release, Albee said in an interview in the Paris Review that “only the emotional aspect shows through. The intellectual underpinning isn’t clear.” While Albee has been kind to the film, he says “they fucked up a lot, too.”

“They changed whole sections, and they were not faithful to my intention,” he gripes. One of the biggest leaps came in the hiring of Elizabeth Taylor, who won an Academy Award for her performance. Taylor was in her early 30s at the time, playing Martha, 20 years her senior.

“She’s much too young, she looks wrong, but why not hire her? Whose aesthetic is that?” Albee asks. “Not mine. I believe the comparative question came up, ‘Do you want Bette Davis or Elizabeth Taylor playing Martha?’ My answer was and would be Bette Davis.”

Albee naturally isn’t as hard on the productions he has had control over: “Most productions that I allow to happen are good jobs,” he says. “As long as they’re honest and try hard, and succeed to a certain extent, and tell the truth and don’t lie, that’s all you can ask.”

Tracy Letts, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his 2008 play August: Osage County, stars in the current revival, giving a performance that’s been called one of the most revelatory Georges yet. He told the Wall Street Journal, “George and Martha are part of our cultural fiber, and we see them reflected throughout this culture in ways we don’t even recognize.”

Perhaps it’s because much of Woolf exists on a subtextual level. Its themes emerge in moments that could slip past you, like when George picks up a book and reads a line aloud — “And the West, encumbered by crippling alliances and burdened with a morality too rigid to accommodate itself to the swing of events, must eventually fall” — then laughs “ruefully” and hurls it away.

“I always write about politics — sometimes it’s rather disguised,” Albee says. “How could you write about the country and your people if you don’t talk about politics among many other things?”

An outspoken liberal, Albee should have as much to write about his country as ever. “We’re in terrible trouble, morally, politically, and intellectually, in this country, and I’m desperately worried about it,” he told the Telegraph last year. More worried than at any point previous?

“Probably. And also less,” he adds, his eyes flickering.

This story originally appeared in Issue 18 of our new weekly iPad magazine, Huffington, in the iTunes App store.