War is hell for everyone involved, including wildlife. But beyond the heat of the battle — where large tracts of land are often set aside for training, storage or other purposes — human conflict can actually be a boon for wild plants and animals.

One well-known example is the Korean Demilitarized Zone, a forested border between North and South Korea where the danger to people has created an inadvertent nature preserve. But smaller military menageries exist in many parts of the world, including North America, and some are less accidental than others. The U.S. military is increasingly embracing this role, for example, protecting national ecology as well as security.

"The Defense Department has a dedication to the environment that is wider in scope than a lot of people are familiar with," said John Conger, acting deputy undersecretary of defense for installations and environment, at a panel discussion on the issue last month. "We spend $4 billion a year on our environmental programs."

The U.S. military manages nearly 30 million acres of land nationwide, Conger added, on which it hosts 420 federally listed endangered or threatened species and 523 at-risk species. About 2 percent of the former and 14 percent of the latter exist only on Department of Defense property. And according to a recent report by the Associated Press, DOD spending on endangered and threatened species grew by nearly 45 percent over the past decade, from about $50 million in 2003 to about $73 million in 2012.

The Pentagon doesn't have a stellar reputation as an ecological steward. Military leaders have long sought exemptions from environmental laws, and the Navy still frequently clashes with animal advocates who say its sonar harms whales. At the same time, though, U.S. armed forces have been quietly setting aside swaths of habitat for hundreds of vulnerable plants and animals, often partnering with environmental advocacy groups.

The military's ecological efforts vary widely in scale. The Army's Joint Base Lewis-McChord, for example, has installed bridges over streams to prevent military vehicles from damaging the waterways and disrupting salmon spawning grounds. In July, the base also received $12.6 million from governments and nonprofit groups to preserve prairie habitat for Mazama pocket gophers, Taylor's checkerspot butterflies and other native species.

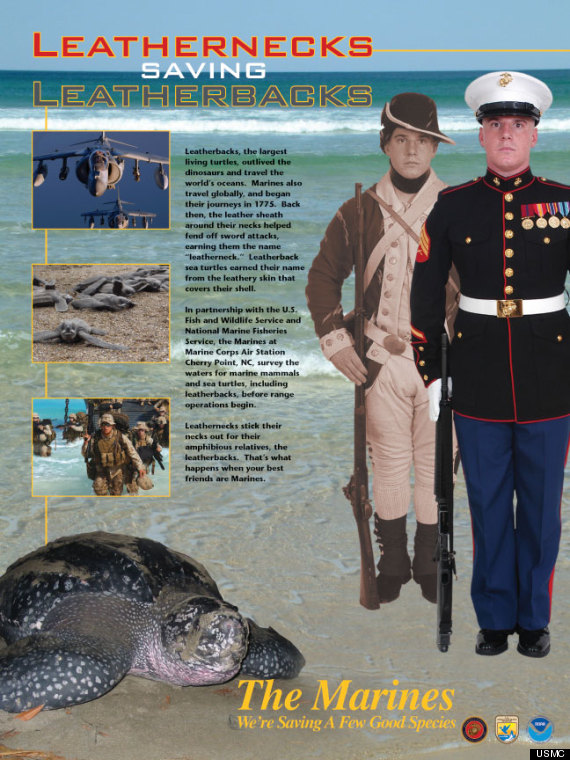

Similar programs are under way at bases across the country. Threatened red-cockaded woodpeckers are thriving at Army and Marine bases in North Carolina, as are endangered sea turtles. A rare subspecies of loggerhead shrike is also staging a comeback on California's San Clemente Island — growing from just 13 birds in the 1990s to 140 today — even though it shares the habitat with a Navy bombing range.

This coexistence isn't necessarily selfless, as the AP points out: If endangered species decline too much, military bases could face tougher rules or even be forced to relocate. Conger acknowledges this, telling the AP "our conservation efforts are first and foremost focused on protecting readiness and eliminating the need for restrictions on training."

Regardless of the military's motivation, though, it's in a unique position to influence the fate of American wildlife. According to a report by nonprofit conservation group NatureServe, DOD territory harbors a greater density of endangered species than any other federal land-management agency. It has nearly seven times more threatened and endangered species per acre than the Forest Service, for example, with especially dense concentrations in Hawaii, California and Florida.

The Pentagon still struggles to share land with some endangered wildlife, such as desert tortoises the Army has relocated from Fort Irwin in California. But one of its most persistent ecological problems is now at sea, where Navy sonar exercises have raised widespread concerns about noise-sensitive whales and other marine mammals.

"As part of these exercises, the Navy will repeatedly broadcast high-intensity sound waves into a vast stretch of ocean, containing some of the most biologically productive marine habitat in the United States," environmentalists argued in a 2012 lawsuit against the use of naval sonar off the U.S. West Coast, one of several such cases in recent years.

But as the AP reports, the DOD has already learned what can happen if it's too cavalier about the wildlife whose habitats it shares. San Clemente Island is currently the U.S. Navy's only ship-to-shore bombing range, but it used to have two: A former range on Vieques, Puero Rico, was closed in 2003 after years of protests over the environmental and health effects of naval exercises. Much of Vieques is now a national wildlife refuge.

"If we were to abuse the island," a naval commander tells the AP, "we would lose it."

Many environmentalists and scientists are still worried about the effect of sonar on whales, and while the Navy has at times reacted defensively to such concerns, it's not ignoring them. As part of a "ground-breaking" behavioral response study on cetaceans and sonar, two Navy ships recently joined independent researchers off the California coast to tag several whales and dolphins. The Navy is currently seeking renewal of federal permits for testing and training exercises in the Atlantic and Pacific, and data from such studies are used in yearly "adaptive management discussions" with the National Marine Fisheries Service. A second phase of the research is slated to begin in September.

"USS Dewey was honored to be a part of this vital study," Cmdr. Jake Douglas, commanding officer of USS Dewey, says in a statement. "We take environmental stewardship seriously in our role as operators, and want nothing more than to be able to do our mission while protecting our environment."