ORLANDO, Fla. -- The same week protests erupted around the nation over the acquittal of George Zimmerman for the shooting death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, 800 school police officers attended a training conference on school violence in a nearby central Florida hotel.

The conference, organized by the Alabama-based National Association of School Resource Officers, gave these school officers lessons on safety, advocacy and warning signs in troubled teens. Attendees chose from a wide array of sessions and events, ranging from a gun safety presentation organized by the National Rifle Association to simulated laser-gun training. Defense vendors were there, too, hawking everything from non-lethal munitions to tourniquets to radio transmitters.

How do we keep our children safe from violence? It's a question the country has been asking itself over and over again in the past year, which has witnessed the horror at Sandy Hook Elementary and the fierce debates over Martin's death. For schools that educate even the youngest Americans, the answer, increasingly, is to arm up.

Traditionally, school districts have paid for guards in middle and high schools. Because, as at Columbine in Colorado and Red Lake, an Indian reservation in Minnesota, those higher schools have been primarily where the shootings have happened. But in the aftermath of Sandy Hook, a school filled with young children, attention is now being increasingly directed to elementary schools as well.

NASRO, a voluntary membership organization for school resource officers, formed in 1991 with the goal of training officers how to function in schools. The group grew tremendously in the wake of the Columbine school shooting but diminished around 2009 as the recession sank in. NASRO's conference has been a primary means for training officers: in 2008, 1,200 SROs attended the conference; the next year, it fell to 700. Last year, NASRO could only fill 45 classes. In 2013, that number spiked to 92, its director Mo Canady said.

At this year’s conference, aspiring school officers could take classes in marksmanship, crisis management and bullying prevention. They could learn about the "proven benefits of non-confrontational interview and interrogation techniques with the millennial generation." They could also participate in "juvenile justice Jeopardy" and a boisterous round of karaoke. But the conference's linchpin in the summer after Newtown was "active shooter response" training.

Since the Newtown shooting, nearly every state has introduced some form of school-safety legislation. These proposals include emergency planning, facility upgrades and funding for new therapists. About 30 states have weighed measures to require armed guards of some sort in schools. At least seven have passed laws to allow approved teachers or other volunteers to be armed while on school grounds. Many districts are adding armed security officers on their own, without state or federal funding or mandates. Many of those officers come from local police departments, and are paid by the school district, the police department or through a cost-sharing arrangement between the two entities. And the Department of Justice announced new grants in late September to fund the creation of 356 new school resource officers.

Civil rights activists, however, see this move as a potentially harmful, knee-jerk reaction, claiming there's little research to prove that armed guards are effective in making schools safer; that other methods work better; that such officers' presence can sometimes lead to increased arrests and suspensions, particularly of minority students for lesser infractions. These groups, including the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, the American Civil Liberties Union and the Advancement Project, sent a letter to Congress earlier in the summer begging them not to fund additional officers.

School resource officers and their advocates argue that properly trained police, even with guns, can help by building trust as mentors to students of all ages. Several SROs interviewed at the conference said that they use every possible alternative before arresting students. "Locking up a student is the last resort," said Anthony Turner, an SRO in Miami-Dade's schools. "You don't just rough 'em up and yell at them and lock them up, but the public at large just doesn't get to see that part."

In light of the Sandy Hook tragedy and countless other violent gun deaths, including Martin's and the mass shooting at Washington, D.C.'s Navy Yard in September, politicians and lobbyists have fought for a stricter set of gun control laws, but those efforts have largely been stymied. Practically speaking, this means that it is no harder now for would-be school shooters of the world to get their hands on guns than it was in the months before the shooting at Sandy Hook.

So the answer to gun violence in schools, according to the NRA and school police alike, boils down to more guns in schools, either in the hands of trained police or teachers. Polling, however, shows that more guns are not what the country wants. We're arming ourselves to make us feel safer, advocates say, but the net effect is not working for everyone, and especially not for minorities. "After the Trayvon Martin case, everyone knows that laws are rarely enforced equally," said Lisa Thurau, whose Cambridge, Mass.-based Strategies for Youth trains police to work with children. "Especially when it comes to people's different characteristics."

ARMED GUARDS FOR TOTS?

After the devastating 1999 Columbine shooting in Littleton, Colo., the number of school resource officers throughout the country doubled. But that growth was generally confined to high schools and some middle schools, those buildings that seemed most susceptible to the unique troubles of adolescence in America.

Newtown, according to Pepperdine University School of Law professor Bernard James, changed that. "Newtown still traumatizes us because it happened at an elementary school. Elementary schools were not thought to be dangerous," he said. "Newtown is shaping education reform by focusing the safety debate down at the elementary school level."

Perhaps ironically, even the school board that represents Newtown voted down a plan in April that would have placed SROs in its elementary schools, according to Newtown middle school safety officer Lenny Penna. "We're hoping this year to come, we will increase the SRO program so we can have one in every school," Penna said at the conference. "It's very political; it's costly, so they had to work out all of the financial issues." At the time, the school board voted down the plan because it was too expensive. (In late September, the Department of Justice awarded Newtown $150,000 in grant money that ultimately allowed the town to create these positions.)

Still, other districts are responding to Sandy Hook by putting armed guards and police in schools with very young children. Federal surveys that track the number of armed officers in schools are not current, so independent figures are not available. (NASRO's own estimate puts 10,000 SROs currently working in schools around the country.) If news reports and interviews with NASRO members are any indication, the practice is spreading rapidly.

School districts near Newtown are amping up their elementary school patrols. Public schools in Middletown, Conn., now have police officers in each school at peak times, and they will get school resource officers in eight elementary schools, according to the Hartford Courant. Taxpayers in Redding, Conn., voted to pay for an officer to police the district's elementary and middle schools. In West Hartford, Conn., the school district paid for an additional $250,000 in school security this year, including increasing the number of guards who rotate between its elementary and middle schools.

Keith Schiffer, a tall man with a handlebar mustache and soulful eyes, spent 10 years working as a corrections officer in St. John's County, south of Jacksonville, Fla. His wife wanted him to have more normal hours, so he started doing rounds in elementary schools. He now works in a high school there.

Schiffer's district, he says, is also beefing up its elementary school security team with more SROs. "Elementary schools are scared to death of us," Schiffer said. "Everything has to be smiles. You kind of just stay in the hallway, don't go into the classrooms. Kids are so enamored with you, they just want to touch your weapon and your badge."

Within 30 minutes of the Newtown shooting, Nick Derzis, a police chief for Hoover, Ala., who has served on NASRO's board for seven years, sent some of his officers to police the local elementary school. Parents loved it, he says. The department received "an overwhelming response" of thank you calls and emails. "I'm just a firm believer in having police in schools," he said, "obviously for the safety factor." Derzis said he kept one officer in each elementary school for the duration of the year, and those positions are funded until the end of September. He's hopeful he can get their funding extended permanently.

Charlotte County, a Florida school district, is adding police presence to its elementary schools, says Larry Langston, who works as a school resource officer there. "That's the plan we put into action," he said. "It was important, so the school board and the sheriff found the money." They're funding eight such employees. Miramar, another Florida district, will have one officer in each of its elementary schools for the 2013-2014 school year.

School districts in Texas have also been eager to arm up. Fort Worth elementary schools are getting 10 volunteer guards. Southlake, a district in North Texas, will have full-time armed police in its 11 schools, including elementary schools. Parents have warmed up to them, according to the Star-Telegram. After meeting her school's guard on the first day of the year, mother Angela Smith told the paper, "He's not a big, scary policeman."

WHAT IS AN SRO, ANYWAY?

With all this increased patrolling, districts are investing in training police for elementary schools. That training, says Canady, NASRO's director, is key: it's what distinguishes a school resource officer from a police officer who is merely assigned to a school.

"An SRO is a concept, or a philosophy," said Canady, a trim man with white hair and a thick southern accent. "There are school police that function from an SRO philosophy, and people who call themselves SROs who don't function from that philosophy." That philosophy involves the much-touted "triad concept" that marries the roles of law enforcement, educator and informal counselor.

The distinction between a trained and untrained SRO is what allows groups like Canady's to say they're not in favor of more armed guards in schools, like the NRA. "We don't want armed guards in schools. We're not armed guards. We're professionally trained to work in schools," Canady said. "No SRO wants to be an armed guard. They don't want to stand guarding the door. What if we're guarding the front door and something happens at the other end of the school? Every time I hear the armed guard question, I cringe."

To illustrate the importance of that distinction in training, Canady points to NASRO's class offerings, particularly to a class known as "live shooter training."

Chris Wallace, an instructor from the Ohio-based Tactical Defense Institute, runs the advanced course. Wallace, a tall, lean man with a salt-and-pepper goatee, wears two handguns atop his pockets, a star-shaped badge at his waist and a baseball cap. He started classes in a nondescript conference room, asking questions like, "How many of you ever leave your homes without your weapons?"

One of his pupils, Darren Campbell, an officer from Topeka, Kan., was abruptly moved to the school beat in the middle of the year. His district is also trying to secure funds for SROs in the elementary school. He came to NASRO, he said, because he wanted to make sure he knows how to relate to kids, especially the youngest ones. "Knowing I'm the one person with a gun who had this training is important," he said. "I knew my role was to make a connection with the kids."

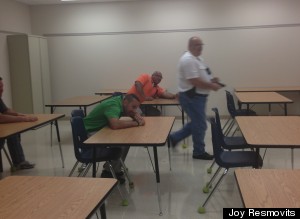

Early one morning during the conference, Wallace leads his six pupils across a hot, sprawling public-school campus. They file into a windowless middle-school classroom, remove the bullets from their guns and replace them with thin yellow ropes. The next day, the stakes will be higher: They'll be using guns loaded with 6mm airlift plastic pellets. Getting hit feels like a bee sting.

For the next few hours, the six participants act out different scenarios and role play. Three arrange themselves inside a classroom, playing students and a teacher. Brett, a cop from New Orleans, plays the shooter. He barges down the hall, lifts his gun and yells "bang bang bang!" The gun clicks. "Shooting! More bullets!" yells a cop posing as a student. Robert Blackmon, a fifth-year Maryland school cop, plays himself. He comes down the back of the hallway, walks forward with his gun pointed. Then he walks back from the doorway, points and shoots.

"What went wrong?" Wallace asks his students. "He had too much exposed." Because of the way Blackmon was angled, Wallace said, the shooter could have seen him from the classroom. Then the guard might have been shot, too.

Blackmon acknowledges his error. "You hear the bang, you go in there and you just want to get 'em," Blackmon says. In that regard, the training, Wallace says, aims to make SROs fight the impulse to shoot first and ask questions later. The day before, Wallace had lined up his pupils next to a hotel conference room doorpost. There, he showed them which angles allow a school officer to hit a shooter from outside a classroom without being exposed and possibly shot himself. "You have to think, 'What's my space, what's my angle?' and it's time to take 'em to geometry class," Wallace reminds his students.

Wallace's company is oversubscribed. This year, TDI has 1,400 more applicants than it can accept. More schools than he can recall want to get some portion of their staff trained for safety purposes. "Sandy Hook sent some people one way, and others another way," Wallace said. He can't understand why anyone would oppose more armed guards if they're properly trained. "The more armed people that are around these places, people are less likely to pick it as a target," he said.

"I don't know why people don't get it."

THE SCHOOL-TO-PRISON PIPELINE?

As more resource officers head to schools this year -- particularly to elementary schools -- a group of advocates and politicians worry that putting more guns in schools could be harmful to children in the long run. SROs have doubled their ranks over the past decade, but these advocates question their efficacy. And critics suggest that the presence of SROs will funnel more students into the justice system at a younger age.

Matthew Cregor, of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, is one such critic. When SRO programs grew, he says, arrests and court referrals in some states also skyrocketed. School arrests in Pennsylvania, he said, tripled between 1999 and 2007; Florida sends 45 students a day to court for school-related matters, two-thirds of which are misdemeanors like disturbing assembly. His group, as part of the Dignity in Schools campaign, recently filed a federal complaint against a school district in Texas, alleging that SROs were citing students for misdemeanors like "disrupting public school" because they were cursing. And those citations, Cregor said, were disproportionately handed to African-American students. "The long-term consequences are stark," he said. "It precludes students from getting into college. A first-time arrest doubles the odds that they drop out."

Cregor taught in New York City, but when students cursed, he said, he wouldn't send them to law enforcement. "When SROs are involved, it can add a sense of alienation and distrust, and that sort of thing is precisely the opposite of what schools need to face in the aftermath of tragedy," he said. Cregor's group is trying to prevent any additional federal funds from going into SRO programs, either through an Obama administration proposal or the Senate's appropriations process.

The Advancement Project, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit, is also working toward that goal. "We want to make schools safer and not just give them the appearance of safety," said Kaitlin Banner, the group's staff attorney.

Lisa Thurau, whose group trains some SROs, agrees -- to an extent. "There are some great school resource officers, but there are some who misuse their power on kids," she said. "Every other professional group working with children must be certified in child development, or have some kind of training at least."

People like Banner and Thurau are concerned because reams of data show that school discipline is rarely doled out proportionally. According to federal information gathered in the 2009-2010 school year, 1 in 4 black middle or high school students is suspended in a given year, compared to 1 in 9 students overall. And in places like Texas, suspensions or minor infractions can lead to arrest, fueling what's become known as the "school-to-prison pipeline."

But to many at NASRO, that pipeline is a myth. "There is nothing scientific about the school-to-prison pipeline," James, the Pepperdine professor and a NASRO collaborator, told a room full of school resource officers. "It is a political movement."

James, a charismatic man with pronounced dimples and the cadence of a minister, helped co-author NASRO's report on the state of the profession. He rallied the SROs at an overcrowded early morning session called "School Safety and the School to Prison Pipeline: Fact and Fiction." The concept of the pipeline, James said, is an attack on the safe school movement.

"What I'd like to do is give you talking points ... things that will make it more likely than not that the policymakers ... will be able to think more clearly about the choices that are placed before them," he said. Of people who oppose SROs, he said, "they just don't know what a school resource officer does."

He then mocked the advocates. "That's the mantra and it sings real well," he said. "Oh Lord, they're pushing them out -- that's the song." The bleary-eyed SROs nodded in assent.

When James asked the safety officers how the pipeline rhetoric has affected their lives, his troops seemed bursting with stories. "Our state has been unfairly victimized in this area," one SRO from Mississippi said. Various reports have found an excess of school citations among minority students in that state, and the U.S. Department of Justice found that many schoolchildren in Meridian, Miss., had been arrested without due cause. Then James stopped and asked if there were any reporters in the room. He kicked this reporter out.

The police themselves don't seem to be aware of the racial school discipline gaps reflected in the national data. "I can't say that I've actually seen any data that determines if you're talking about having a disproportionate number of minorities ... arrested compared to others," said Derzis, the Hoover, Ala., police chief. "We pretty much teach our officers, 'We're going to do everything that we can to support an individual.' We're not there to arrest people." And when discipline is leveled, he added, it's usually the school administration that makes that call.

The question doesn't make sense at the school level, said Turner, the Miami school safety officer. "Some places are all minorities, or white or Hispanic, so you're not making arrests of one particular minority," he said. "We don't compare notes on this between school resource officers."

From 1994 to 2009, Canady says, juvenile arrests declined by 50 percent. He attributes that decline to the growth in SROs nationally. "They're finding more productive ways to deal with minor offenses than arrests," he said. "People say, 'We don't want more police in schools because it means more kids will be arrested.' I think it's a valid concern, but I don't think that it's as widespread of an issue as it's made out to be."

And James argues that the pipeline mentality is backwards, because of lower arrest rates overall and rising graduation rates.

But Thurau says that the graduation rates can be misleading, as they don't always include all the students who have been pushed out of school. "The way data is collected makes it hard to know if the rate reflects all incoming ninth graders," she said.

As the new school year starts, even NASRO's leaders worry about school districts' ongoing reaction to Newtown. "We heard a lot of school districts were just assigning officers to the schools," said Kevin Quinn, an Arizona SRO who serves as the group's president. "We don't want to throw random officers in the schools. Certainly not random officers or 'let's arm the staff.' It's not the gun that makes the school safe."