It’s been 22 years since I started noticing Olympic Moms. It's not a coincidence that that’s around the time I became a mother myself. Until then, when I’d followed the quadrennial events, I'd identified with the athletes. (Well, “identified” is probably the wrong word, because I have no talents of the physical sort, but I was riveted by their stories.) As they stood on the podium, I potatoed on the couch, wondering -- what were they thinking, what did it take to get to where they were, and what did it mean to be the best in the world?

Then suddenly, I was identifying with their parents. My son was born a few years after the 1988 Games in Calgary, and by the 1992 Games in Albertville, I was stunned at how someone’s children were receiving these medals, and became misty at the sight of their beaming parents in the stands. What did it mean to raise the best in the world?

Clearly I was not the only one wondering. P&G discovered the athletes' parents back in 2010, in Vancouver, using the tagline the “proud sponsor of moms” and running a tear-jerker ad with the tagline “To their moms, they’ll always be kids.” Then, at the 2012 Summer Games in London, came the soft focus weep-a-thon of a spot titled “Thank You, Mom.”

And as the Sochi Games loom next month, the company is unveiling a new ad today that is guaranteed to soak your box of tissues (no worries, Puffs is a P&G brand) called “Pick Them Back Up.” (Watch the spot below.) There’s also a series of short films featuring 28 athletes and their mothers called “Raising An Olympian,” in case you hadn't wept quite enough.

“While most Olympic sponsors celebrate the win, P&G is focused on the journey through the eyes of the person who taught each of the athletes the daily lessons of character, determination, and commitment that add up to define a champion,” the company says -- which simultaneously makes this mother proud, and also makes her wonder why P&G has left dads out of their equation. But Jodi Allen, P&G’s VP of North American marketing and brand operations, assured me in an interview that “it goes without saying that dads play an important role, too,” and that the company “honors dads through programs from our brands like Gillette.” However, she added, P&G has “found that both the athletes themselves and their dads really welcome the chance to honor the role moms play in helping their kids achieve their dreams.”

Well, if expensive marketing research shows that dads are happy to cede this spotlight, then I shall accept that for the moment and turn the rest of this space to what Allen reminds me is the purpose of the campaign: “As a mom I can relate to those moments of watching my children fall, and being there to pick them up, dust them off and tell them to try again,” she said.“We feel that all moms can relate to this new film because whether your child is an Olympian or not, all moms strive to raise great children.”

Yes, we do. I think that’s what I’ve responded to since my first games as a mom -- that this is what it means to raise a child. You teach and prepare and protect as best you can. You cheer and bask and worry. You pick them up. And then you send them off to take on the world -- while you sit on the sidelines and watch.

Paraolympic snowboarder Amy Purdy and her mother, Sheri (P&G)

So how DO the parents of world-class athletes do it? What, if anything, are the lessons for the rest of us? I asked the mothers of ice hockey player Julie Chu, ice dancers Meryl Davis and Charlie White, slopestyle freeskier Nick Goepper, and paraolympic snowboarder Amy Purdy (all of whom happen to be sponsored by P&G, which put me in touch with the parents and is giving every mother of a U.S. athlete $1000 to help pay their way to the games). Here’s what I learned about being an Olympic Mom:

It’s clear your kids are different from the start.

“He was the baby who didn’t want to be held, he wanted to be moving,” says Linda Goepper of 19-year-old Nick’s childhood in the very not-mountainous Lawrenceberg, Ind. “He always wanted to be in his baby jogger, and I would walk him for two hours -- and always on the bumpy grass because that was more entertaining. He could skate better than other kids. He could swim better than other kids. He started getting calls from coaches in all kinds of local sports, which I thought was ridiculous.”

Linda Goepper and her son Nick, an Olympic freeskier (courtesy Goepper family)

Except when it isn’t.

“Amy didn’t start snowboarding until she was 15,” says her mother, Sheri, of her now-35-year-old daughter. “Back then she did compete a little, but it was never a goal of hers to be an Olympian or anything. It was something she loved, something fun.”

These parents are flexible, redefining their goals as their children redefined themselves.

“Julie always came along to her older brother’s hockey games, it was always a family affair,” Miriam Chu says. “Then one day she saw a poster at the rink that said, ‘Girls can play hockey too.’” Miriam’s answer was to sign 8-year-old Julie and her 10-year-old sister, Christina, up for figure skating lessons, but after three months the girls still insisted they wanted hockey instead. On the theory that “we should give our girls every opportunity,” both girls were allowed to join a team, Chu says. “Julie just fell in love with the sport. Figure skating would not have lasted. She loved being on a team.”

The whole family spends a lot of time in the car.

“I was a school teacher, and I made sure my schedule met with Meryl’s so I could pick her up after school and drive her to the rink,” says Cheryl Davis, whose daughter began figure skating lessons when she was 5 and has been ice dancing since she was 8. “We had a van tall enough that Meryl could stand up and change her clothes and eat her snack on the way. Then I would leave her at the rink, go pick up her brother, drive back to the rink, bring them both home for dinner.”

Cheryl Davis and her daughter, Meryl, world and Olympic ice dance champion (courtesy Davis family)

And also a lot of time near rinks, and slopes, and venues.

“When I wasn’t in the car driving, I was at the rink watching,” says Jacqui White, mother of Meryl’s ice dance partner, Charlie. “And then when they started traveling to tournaments, it was a lot of time away from home. I work, we have other kids, and I’d say 50 percent of the time I wasn’t working, I was spending on Charlie’s skating.”

It’s an Olympic feat to juggle the needs of ALL your children.

“My son is three years younger than Meryl,” Cheryl says, “and I tried to take him on trips by himself to balance the times I traveled with Meryl. Also, while we were at tournaments, he would go snowboarding with his dad. That would be their time. He didn’t seem to be bothered by it. He wasn’t jealous of what Meryl did, but I tried to give them both the same. We tried not to talk about skating around him all the time. We tried not to make skating our whole world.”

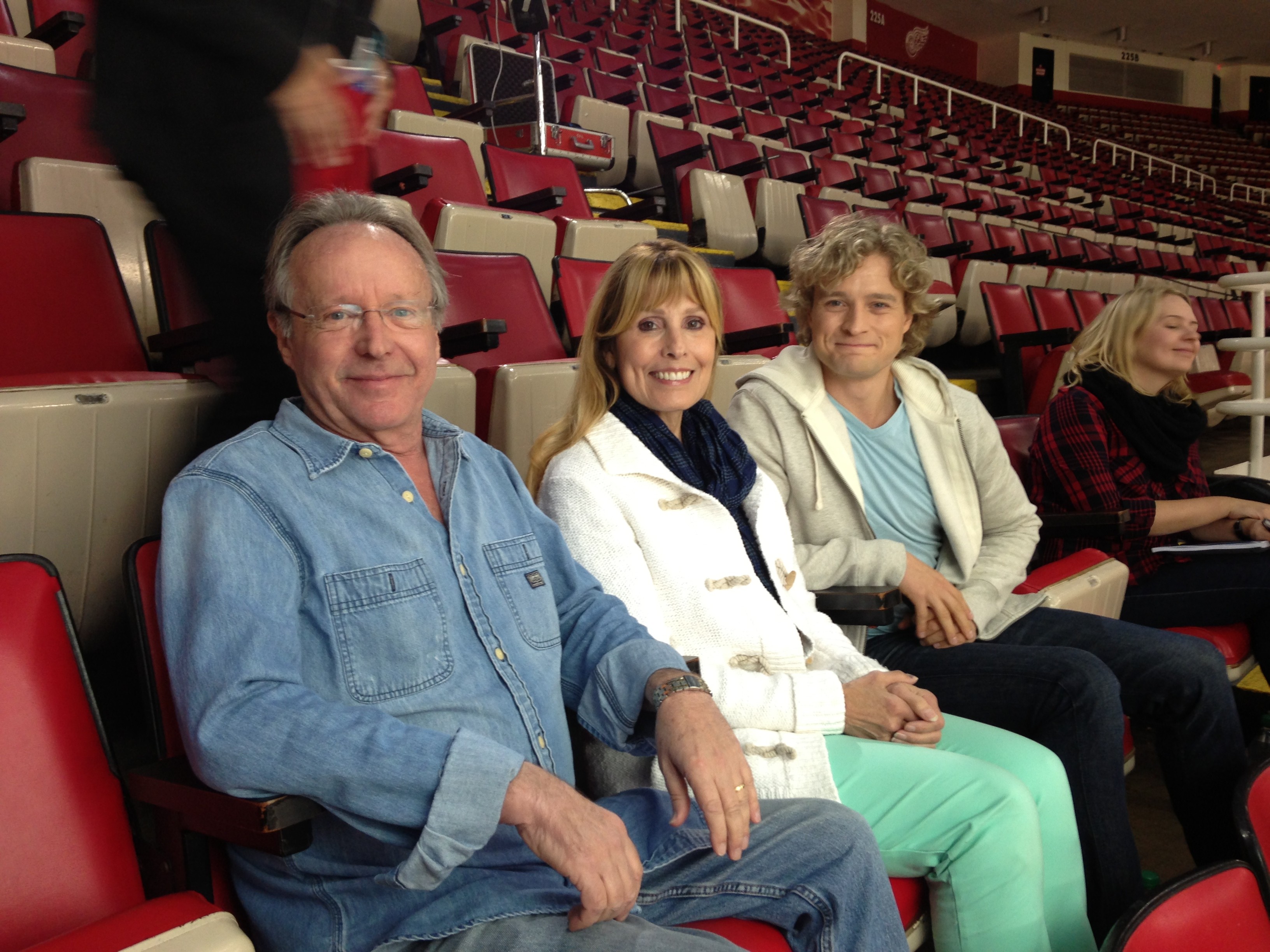

Cheryl Davis and Jacqui White became close friends while traveling to ice dance competitions with their children. (courtesy Davis family)

Adds Linda Goepper, “My two girls were gymnasts, and my husband would take Nick to his skiing competitions while I was traipsing around the country taking the girls to their gymnastics competitions.” And then there was the youngest brother, Jason, who somehow had to get to his more traditional team sports, like baseball and basketball.

The logistics are easy compared with balancing all those dreams.

“I would never say she was better -- I want to say committed, she was determined,” says Miriam Chu of the fact that while all three of her children were hockey players, only Julie was world-class. “Richard was perfectly happy to play through college. He knew his limitations and strengths, he reached his goal. Christina liked hockey, but only wanted it through high school. But Julie, she had the fire and said, ‘I want to make the national team.’ She didn’t dream of the Olympics back then because women didn’t play on that level until the Nagano Games of 1998. She made her first Olympic team at the age of 19, and has won three Olympic medals, four World Championship golds, three World Championship silvers and will play forward for the U.S. team in Sochi.”

At the Goepper house, there was a different kind of competition. Nick’s sisters reached Level 9 in the highly competitive sport, but had to retire in their early teens because of injuries -- while Nick won the silver medal in the slopestyle at the 2012 Winter X Games, and then the gold in 2013. “But they kept him in his place,” Linda says, “because they were even more athletic than he was. After dinner they would challenge him to wall sits, sit-up contests, leg swings. He never got to feel like he was King Tut around the house because his sisters could always beat him.”

You spend a lot of money.

“We put hundreds of thousands of miles on our cars,” Miriam Chu says, “and once they got into travel hockey we started adding staying at a hotel, meals in restaurants. As they were growing, we had to replace their skates, their equipment. Somehow you make do, you’re able to do it so that your kids can live their dream. There were a lot of parents who struggled.”

Miriam Chu and her daughter, Julie, Olympic hockey player (P&G)

Linda Goepper says, “Nothing got repaired around here, we had a hard time paying bills, we drove cars that had 300,000 miles on them. We self-sacrificed -- sometimes too much.” When Nick was 13, his father lost his job and was out of work for two years. Nick took on any hourly work he could find -- babysitting, lawn mowing -- to pay his skiing costs, Goepper says. When he was 15, he was offered a full scholarship to the Windells Academy, a prestigious Oregon ski school, and moved away from his family full-time. “That was a different kind of cost,” his mother says.

You can’t fix it when they get hurt.

Davis and White were months away from the National Ice Dancing Championships in 2005 when Charlie broke his ankle playing hockey. Off the ice for weeks, his mother worried that he would never go back. “For a while, he was having so much fun doing all the sorts of things he might not have had time to do because of skating,” she says. “We just stepped back and let him figure it out. Soon, he was chomping at the bit to get back out there.” Charlie and Meryl won the U.S. Junior National Ice Dancing title in 2006 and the national title in 2009, 2010, 2011 and 2012, the world title in 2011 and 2013, and the silver at the 2010 Olympic Games.

Charlie White (R), world and Olympic ice dance champion, and his parents (courtesy Davis family)

Sheri Purdy, meanwhile, never worried that her daughter wouldn’t want to get back on the slopes -- but rather that what she wanted might never be possible. Amy was 19 when she lost both legs and her spleen to a form of meningitis that nearly killed her. “It was her passion for snowboarding that saved her life and got her back on her feet,” her mother says. That meant designing prosthetics with her father out of duct tape when commercially available options didn’t work with a snowboard. It also meant a transplanted kidney donated by her dad. Now, Amy is considered the highest-ranked female adaptive snowboarder in the world. “I learned not to ask things like, ‘Are you sure you can do this,’ Sheri says, “because she was sure, so I had to be sure.”

You learn to manage your nerves.

“I think it’s probably scarier for strangers to watch Nick do back flips off trees than it is for me,” Linda Goepper says, “because I know he can do it. What he does is dangerous, but he doesn’t put himself in harm's way. He’s very calculating, very cautious. He learned some of that from his sisters, from the gymnastics world, where you don’t start off learning the big trick, you learn all the bits and pieces.”

That said, “I do get really nervous when I watch him compete,” she says, “but it’s mostly about landing cleanly so he can score high and win the competition. ... And I do get a little more nervous when the wind is blowing and it is snowing."

You learn to let go.

“When she first got hurt, we were glued to one another for months,” Sheri Purdy says. “We had a parenting do-over, it was like caring for a 3-year-old. It took me a while to let her go again. But watching her rebuild from scratch, I don’t even think about her getting hurt any more. She almost lost her life to an invisible enemy, and now I have all the confidence in the world that she can do anything she puts her mind to.”

But never completely.

“This year Nick had two surgeries -- a tonsillectomy and hand surgery,” says Linda Goepper. “So he was home while he recovered, and we saw a lot more of him than usual. I got to baby him again. Is it awful if I say that was awesome?”