Looking a bit like a dolphin, but with a long slim snout filled with pointy teeth, one species of ichthyosaur was practically invisible in the murky depths of Jurassic seas, thanks to dark pigmentation that covered its entire body. That’s one conclusion of a new study that provides an unprecedented peek at the coloration of sea creatures alive during or soon after the dinosaur era.

Fossil pigments reveal melanic (dark) coloration of extinct marine reptiles. Note that the leatherback turtle (top) and mosasaur (bottom) are countershaded (have a dark back and light belly), whereas the ichthyosaur (centre) is uniformly dark-colored.

Fossil pigments reveal melanic (dark) coloration of extinct marine reptiles. Note that the leatherback turtle (top) and mosasaur (bottom) are countershaded (have a dark back and light belly), whereas the ichthyosaur (centre) is uniformly dark-colored.

The new findings “are marvelous, so cool,” says Anne Schulp, a vertebrate paleontologist at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden, the Netherlands, who wasn’t involved in the research. “This is paleontology well beyond the bones, and [the team’s] arguments make perfect sense.”

Soft tissues aren’t often preserved in the fossil record. As a result, figuring out what ancient creatures looked like—and particularly what colors they might have been—was by necessity speculative. But in recent years, scientists have developed high-tech methods to map the chemical traces of soft tissues in the rocks surrounding fossils, which in turn have helped them visualize the remains of pigments—almost literally bringing prehistoric colors back to life. Most previous efforts have focused on fossil birds and preserved remnants of their feathers, says Johan Lindgren, a vertebrate paleontologist at Lund University in Sweden. Now, he and his colleagues have used those techniques to analyze the fossils of ancient marine reptiles.

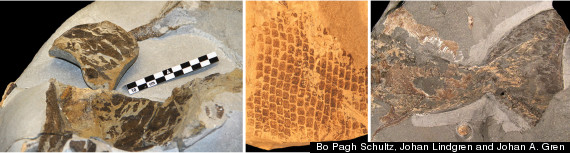

Skin from a 55-Myr-old leatherback turtle (left; scale bar, 10 cm), scales from an 85-Myr-old mosasaur (center; scale bar, 10 mm) and tail fin of a 196–190-Myr-old ichthyosaur (right; scale bar, 5 cm).

Skin from a 55-Myr-old leatherback turtle (left; scale bar, 10 cm), scales from an 85-Myr-old mosasaur (center; scale bar, 10 mm) and tail fin of a 196–190-Myr-old ichthyosaur (right; scale bar, 5 cm).

For their study, the researchers looked at three sets of fossils (now housed in museums in Denmark, England, and Texas) of widely disparate creatures from different eras: a leatherback turtle that lived about 55 million years ago, a large predator called a mosasaur that lived about 86 million years ago, and an ichthyosaur that swam the seas between 190 million and 196 million years ago. (The ancestors of each of these creatures had once lived on land, so all three were air-breathers.) In all three fossils, outlines of soft tissue were preserved in the surrounding rock as dull black material. Paleontologists have long presumed such films to merely be carbon-rich remnants of tissues, Lindgren says. But a look at those materials with a scanning electron microscope revealed dense layers of tiny, rugby ball–shaped structures ranging between 0.5 and 0.8 micrometers long. These tiny bits are the same size and shape as the pigment-bearing structures (called melanosomes) found in the skin and scales of modern-day lizards and in the feathers of birds. Their ovoid shape suggests the pigments were black; melanosomes that lend a red or yellow color are typically spherical, Lindgren notes.

When the team bombarded the fossils with charged particles and then analyzed the particles that were knocked from the surface (a technique called time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry), they chemically identified the remnants of eumelanin, a pigment that typically lends a black or brown color to skin or feathers. The rocks surrounding the preserved tissues didn’t contain the carbon-rich compounds, further suggesting the chemical remnants stem from preserved soft tissues and not ancient sediments, the team reports online today in Nature. Considering the concentrations of melanosomes the researchers found, even if the animals had other pigments that weren’t ultimately preserved, the pigment-bearing areas would likely have been dark gray or black.

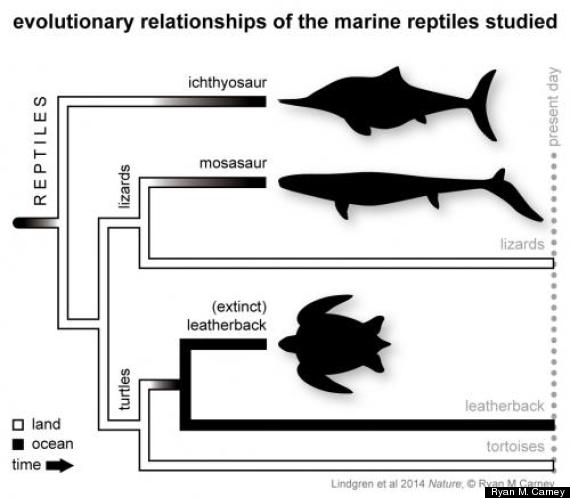

The overall pigment patterns in the fossils are very similar to those of modern-day sea creatures, the researchers note. In the leatherback turtle and the mosasaur, the pigments were concentrated on the upper surfaces of the animals’ bodies. Studies suggest that this dark-above-and-light-below color scheme, known as countershading, helps provide camouflage, Lindgren says. When lit from above (as it would be when the animal was swimming in a normal posture) and seen from the side, the lighter underside would be in shadow, helping the creature blend into the background, he notes. Because these creatures are air-breathers, they would have spent a substantial amount of time at the surface or in the shallow, well-lit portions of the seas.

Evolutionary relationships of the fossil marine reptiles examined. Black branch denotes pelagic cruisers, whereas white branch denotes land dwellers. Note that each reptile lineage independently became secondarily adapted to aquatic environments

Evolutionary relationships of the fossil marine reptiles examined. Black branch denotes pelagic cruisers, whereas white branch denotes land dwellers. Note that each reptile lineage independently became secondarily adapted to aquatic environments

But the ichthyosaur appears to have had dark pigments all over its body. That’s unusual but not unknown among modern sea creatures, Lindgren says. The sperm whale is also dark all over—a color scheme that may help the fearsome predator hide in the gloomy depths where it typically forages.

The pigments may have served other purposes as well. Dark upper surfaces, in particular, help modern-day marine reptiles such as leatherback turtles absorb sunlight while they bask at the surface. That boosts the creatures’ body temperatures, allowing them to grow faster and to forage for longer periods in cold waters.

The team’s research “is very interesting, and it’s not trivial,” says Mike Benton, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom. “Several years ago, people would have said we’d never be able to tell what colors ancient creatures were,” he notes. “But here we are.”

This story has been provided by AAAS, the non-profit science society, and its international journal, Science.