When a black hole swallows a star, things get violent. Very violent.

At least, that's what scientists found in a new study when they used computer simulations to mimic the destruction of a star as it falls into a giant black hole. Just check it out in the video above.

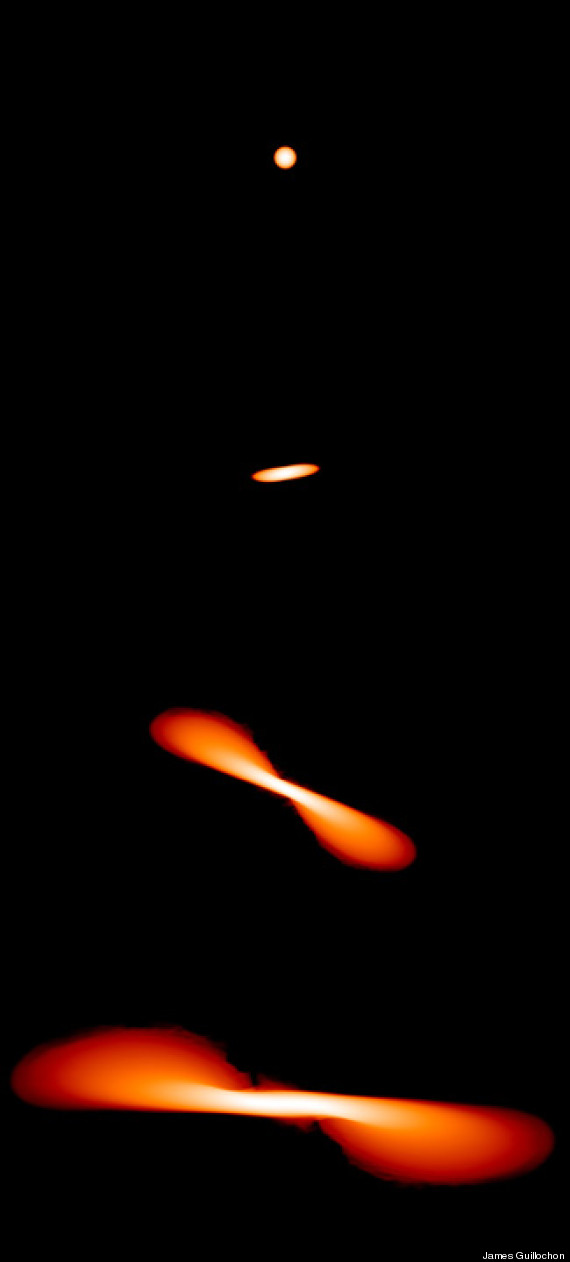

The simulations show that when the gravitational force of a supermassive black hole pulls in a star, the star is stretched into a long blob before it's destroyed. About half of the star's mass may get ejected as a stream of debris and the other half eventually may spiral into the black hole, forming what's called an "accretion disk."

The simulation study suggests that the whole event results in a luminous flare of light — and that light curve contains information about the type of star and the size of the black hole involved in the collision.

"With this simple model, we get a perfect fit to the data, and we're able to explain the light curve in multiple color bands," study co-author Dr. Enrico Ramirez-Ruiz, a professor of astronomy and astrophysics at the University of California in Santa Cruz (UCSC), said in a written statement. "The type of star and the size of the black hole are imprinted in the light curve."

(Story continues below)

When a star first encounters a black hole, tidal forces stretch the star into an elongated blob before tearing it apart, as seen in these images from a computer simulation.

When a star first encounters a black hole, tidal forces stretch the star into an elongated blob before tearing it apart, as seen in these images from a computer simulation.

The researchers said in their study that the simulation model can be used to make sense of a black hole and star collision that was observed in 2012, dubbed PS1-10jh. At the time, scientists thought the disrupted star may have been a rare helium star because they did not detect emissions characteristic of hydrogen in the light curve. But this new study suggests that's not the case.

"It's very unusual to have seen helium and not hydrogen. Stars are mainly made of hydrogen, and stars made only of helium are extremely rare, so this was a huge issue," study co-author James Guillochon, who was a graduate student at UCSC during the study but now an Einstein Fellow at Harvard University, said in the statement.

Instead, the simulations suggest that the accretion disk had not grown big enough at the time when PS1-10jh's light curve was recorded. "The hydrogen is there, you just don't see it because it is so highly ionized," Guillochon said in the statement.

Astronomers call the collision of a star and black hole a "tidal disruption event" (TDE), and in a typical galaxy it happens about once every 10,000 years, according to the statement.

"That means you have to survey the nearest 10,000 galaxies in order to see one event, so for many years this was very much a theoretical field," Ramirez-Ruiz said. “Tidal disruption is elucidating a local population of low-mass quiescent black holes, and it is going to enable us to test the idea that every galaxy has a black hole at its center, even the tiny ones.”

This new study published online in the Astrophysical Journal on Feb. 7, 2014.