Last week, Jonathan Bernstein, writing in Bloomberg View, issued a plea to America: stop watching the Sunday morning political blatherskite shows. I've already complied with this request, and I can report, anecdotally, that my life is much improved. (Did you know that instead of watching "Meet The Press," you can have a bunch of friends over and cook them breakfast? This is the wonderful thing I learned about the world this past Sunday!) The good news, I'm pleased to report, is that America -- save for one demographic -- is largely doing the same, tuning out these shows in favor of having a robust and fulfilling life.

Bernstein makes these urgings in response to a piece that Paul Waldman wrote for The Plum Line in which Waldman offered suggestions for how the Sunday shows could be improved. This sort of piece is becoming something of a Sisyphean genre unto itself -- well-meaning media critics seeking to inject the moribund "public affairs" shows with a new life. Preeminent among Waldman's suggestions is to simply book a better class of guest:

First, ban all party chairs, White House communication staff, party "strategists," and anyone else whose primary objective is to spin from ever, ever, ever appearing on the show. Ever. To ask a question I've raised elsewhere: Has anyone anywhere in the United States turned off their TV and said, "Wow, that interview with Reince Priebus was really interesting"? Of course not, and the same applies to his Democratic counterpart, Debbie Wasserman Schultz. That's because their job is to deliver talking points, and they do so with a discipline worthy of the Marine Honor Guard, no matter what questions they're asked. And they get plenty of time on cable, so why waste valuable minutes on a Sunday show by letting them repeat the same talking points they've recited 100 times that that week?

I understand Waldman's objections. Most of the people -- and "most" is perhaps an understatement! -- who get booked on Sunday shows fall into one category of public figure: "People Who We Already Know What They Are Going To Say And Will Fail To Surprise Us." In 2012, we learned that the people who worked on President Barack Obama's campaign thought that Obama was the best candidate and that he was going to win. We similarly learned that the people who worked on former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney's campaign thought that Romney was the best candidate and that he was going to win. And we learned this, week after week, for months. Believe me, I was sitting there, waiting for, say, Stephanie Cutter to slip up and say something different, but it never happened.

It gets even sillier every time a news story breaks that forces some Beltway politico to arise on Sunday and attempt "the Full Ginsburg" -- that thing where someone proceeds from show to show in an inhuman attempt to submit to an interview with every Sunday morning gatekeeper. Those were the mornings where recapping the Sunday shows in liveblog form were the easiest: I knew that as soon as one Sunday morning interlocutor had finished their interrogation, I was mostly going to hear the same questions and the same answers repeated three more times. It's very clear that the producers of these shows don't stop to consider the sort of questions their competitors will inevitably ask, for the purpose of asking something different. Sunday morning journalism is often nothing more than checking off boxes and notching bedposts.

Bernstein notes that in their heyday, these shows offered politicians something rare: a forum to engage in "send[ing] up trial balloons, or [engaging] in public, high-profile bargaining." In short, the subtle work of partisan dealmaking was served. But those days are over. Now, the Sunday shows simply serve as a venue for prestige arbitrage, where having regular access to deemed-to-be-important people is an end in itself. And so these shows have slowly morphed into salons for the powerful, where one can only get so adversarial before a plum booking is put at risk.

Waldman is not the first person I've seen suggesting that the Sunday shows just book different people. And he's not the first to call upon bookers to quit endlessly inviting Senator John McCain to appear, like the proverbial bad penny. Waldman writes: "So how about, as a first rule, the people you bring on should 1) know as much as possible about the things you’re going to discuss, and 2) have little if any interest in spinning?"

This sounds pretty good in theory, but there's a reason those sorts of people don't get booked. Knowledgeable, substantive people tend to want to use their time on camera to explain complexities. They speak in paragraphs, not sentences. They tend to be capable of real argument. They don't necessarily come to the set governed by Beltway politesse. So, from the perspective of Sunday show producers, they're all loose cannons. What the producers of these shows are looking for are polite, concise talking heads who know where their light is, can hit their mark, and offer answers brief enough so that there's plenty of time to pass the ball to whoever else happens to be in the room. Sunday hosts don't know what to do with long, complicated explanations, and they aren't listening to them anyway.

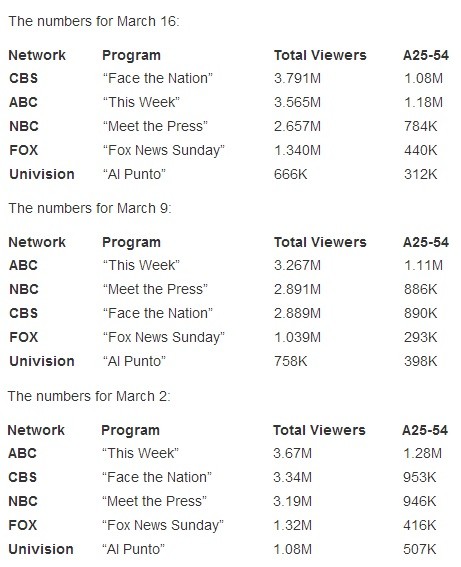

There's just no place for the sorts of guests that Waldman prefers on the traditional Sunday morning chat show, and I don't see that changing any time soon. What is changing, however, is that Americans, by and large, are finding better things to do with their lives. Take a look at the ratings for the Sunday chat shows from the first three weeks of March, via TVNewser:

With the slight exception of Univision, this has become something of an inescapable trend for these programs -- Americans between the age of 25 and 54 just couldn't care less about them anymore. The single biggest problem the Sunday shows face is that no one has yet figured out how to make their core audience immortal.

Bernstein urges people to take aim at the Sunday shows by simply ignoring them:

The only solution is to stop paying attention. Don’t get involved in critiquing the mix of guests, or the topics, or anything. And if one of the shows actually makes some news, there are plenty of opportunities to catch up later, just as there is with any other program.

I stop short of not getting involved in critiques of these shows -- you would be doing yourself a disservice by missing out on Charlie Pierce's weekly dispatch, for one thing. My recommendation is to spend your Sunday morning making a phone call to members of the Sunday show audience. They are, after all, your parents and grandparents, and as the Sunday show producers well know, your time on this earth with them is limited. And if you love them at all, you'll probably agree that they deserve much, much better than David Gregory and George Stephanopoulos.

READ THE WHOLE THING:

Stop Watching the Sunday Talk Shows [Bloomberg View]

Can the Sunday shows get better? [The Plum Line]

[Would you like to follow me on Twitter? Because why not?]