High school test scores released by the federal government Wednesday provide fresh evidence of a troubling theme in American education: Students seem to perform worse on tests as they advance through the public school system to higher grades.

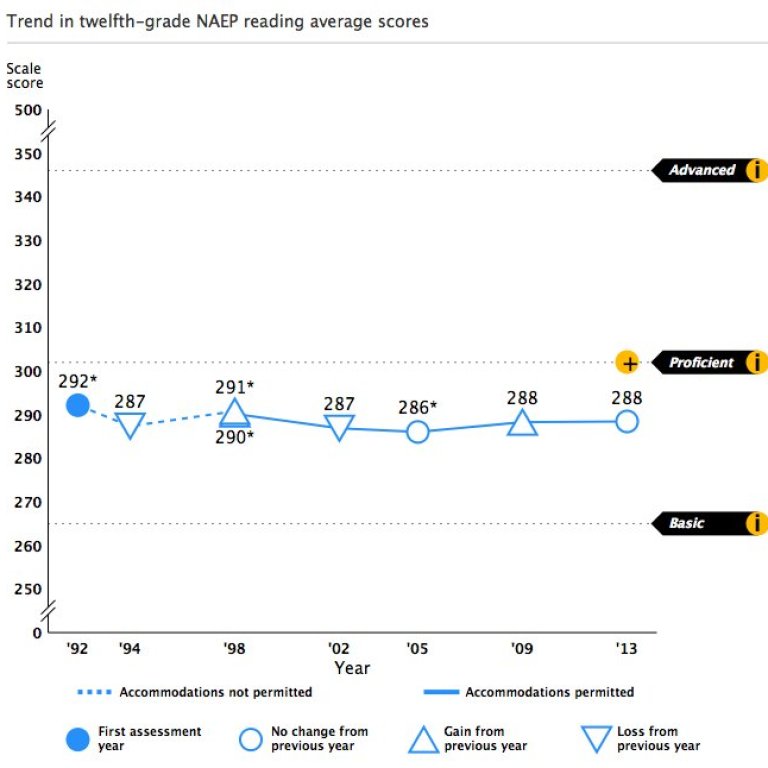

America's high school seniors have mostly stagnated on the National Assessment of Education Progress in reading and math at least since 2005, when a comparable version of the math exam was first given, according to the report. In 2013, the latest NAEP math test, seniors scored an average of 153 out of 500 -- three points higher than in 2005. In reading, students lost ground, dropping from 292 in 1992 to 288 in 2013. In both subjects, achievement gaps between ethnic groups didn't diminish.

“Despite the highest high school graduation rate in our history, and despite growth in student achievement over time in elementary school and middle school, student achievement at the high school level has been flat in recent years," said U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan. "Just as troubling, achievement gaps among ethnic groups have not narrowed."

As white students likely become a minority in the nation's public school population for the first time next school year, Duncan said schools "must do better for all students, especially for African-American and Latino students.”

On NAEP tests administered to fourth graders and eighth graders, students have shown incremental growth. In fourth-grade reading, scores increased from 215 in 1988 to 222 in 2013.

In fourth-grade math, scores increased from 213 in 1990 to 242 in 2013. In eighth-grade math, scores increased from 263 in 1990 to 285 in 2013. At both grades, higher percentages performed at advanced, the highest level, than in 2011 or in 1990.

But the high school results barely budged.

This trend is reflected on some international exams, and has led experts to wonder, despite the push for early education, whether America's biggest education problem spot is in the later grades.

"Our high schools take kids who have made incredible progress in fourth grade and eighth grade," said Mark Schneider, a vice president at the American Institutes of Research who previously led the government arm that administered NAEP. "Whatever good we did is gone."

Experts had several possible explanations. "Either our high schools are doing a terrible job, or 12th graders don't care about NAEP," Schneider said. When he oversaw NAEP, Schneider said he saw signs that 12th graders are less motivated than fourth graders or eighth graders to perform on a test that has no bearing on their lives. "They have so much on their plates," he said. "Motivation has always been a problem -- that's the optimistic assumption."

On the other hand, Schneider said, "states and schools have lied about the rigor of their courses. … Students aren't learning what they should be learning in high school."

Current test administrators say they have reason to believe motivation is less of a factor than before. On a Tuesday call with reporters, Cornelia Orr, executive director of the National Assessment Governing Board, said test-takers now see a motivational video before answering questions. "It's a little bit more of an urban myth about students just blowing off a test when they sit down to do it," she said.

Similarly, John Easton, who heads the Institute for Education Sciences, said "we are feeling confident in 12th graders' enthusiasm at this point."

Peggy Carr, who oversees NAEP administration, said in an interview that the Education Department will soon release a paper proving that the patterns of persistence and engagement are not all that different between fourth graders and 12 graders. "It's probably not explained by lack of engagement with the assessment," she said. "There's really no evidence to suggest that's what's going on."

So what explains the stagnation in 12th grade? Carr said it may have to do with sampling. NAEP has been described as the "gold standard" of standardized tests because, unlike many state and local exams, the stakes are low. NAEP results only provide a barometer on performance, unlike state tests, which are used to reward and punish schools and, more recently, to evaluate teachers. So schools have little incentive to cheat or teach to the NAEP test.

In 2013, 92,000 12th graders took the test, the exam's highest participation rate. The sample size included higher proportions of minority students, students with disabilities and English language learners than in previous years.

Over time, as the graduation rate has increased, NAEP has included more students who would have dropped out in previous years. These students are often the lowest performers, and this demographic change would not affect fourth grade or eighth grade scores. But it may cause 12th grade scores to lag.

"What's happening is that students who would normally drop out of school are staying in," Carr said. "Students who would normally not be taking our assessment, they're in there now at larger proportions."