WASHINGTON -- A congressional hearing to examine the legacy of President Barack Obama's 2010 Wall Street reform law quickly devolved into a partisan mess Wednesday, with Republicans demanding more loans to low-income minority borrowers, decrying mergers of small banks and pitying the regulatory burden of a community banker who's exempt from the new law's key mortgage rules.

Raising the stakes for this bizarre battle was the testimony of former House Financial Services Committee Chairman Barney Frank (D-Mass.), the only Democratic witness called for the hearing. Frank pounced after current panel Chairman Jeb Hensarling (R-Texas) and other Republicans decried the decline in loan availability for low-income and minority borrowers.

"I was very struck by the frankly schizophrenic approach that the majority seems to be making on subprime loans -- loans to poor people," Frank said. "There's a criticism that under the bill, fewer loans are being made to low-income people -- yeah! That was part of what I thought everybody wanted to do. I thought there was a consensus that too many loans were being made to those people."

Hensarling was particularly vocal about the Dodd-Frank law's effect on minority borrowers, claiming a Federal Reserve study shows that "about one-third of blacks and Hispanics would not be able to obtain a mortgage," based on the rule's requirement that monthly borrower debts not exceed 43 percent of monthly income.

That's true, according to the Fed's 2010 data. It's also generally considered bad personal finance to have that much of your income tied up with debt payments.

But the broader problem is that minority families generally have lower incomes than white families, thanks to widespread institutional racism. Median African-American household income was $33,762 in 2012, compared with median white household income of $55,565.

And issuing expensive loans to families with low income can have terrible results. The proliferation of subprime mortgages during the George W. Bush presidency did disproportionately target people of color. It also hurt them, as many who qualified for better terms were steered into garbage loans with high interest rates. Since most subprime loans were for refinancings, the boom ultimately caused a net loss of homeownership, as many sustainable home financing arrangements were converted to foreclosures.

Dodd-Frank tried to remedy that situation with new consumer protection rules requiring banks to verify a borrower's ability to repay a loan before extending it. At Wednesday's hearing, much of the GOP criticism focused on false allegations about the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's Qualified Mortgage regulation, or QM.

"You don't protect consumers by taking away or limiting products, like the CFPB does through the Qualified Mortgage rule," Rep. Sean Duffy (R-Wis.) said.

The QM rule doesn't ban anything. It's a basic test of whether a loan is designed to line a lender's pockets by ripping off a borrower. And it gives banks special perks for meeting the CFPB's high-quality loan standards, protecting them from predatory lending lawsuits. In practice, that means limiting the amount lenders charge in points and fees to 3 percent of the loan value, banning balloon loans with a big lump sum due at the end of the mortgage, and ensuring that a borrower's monthly debt payments don't exceed 43 percent of monthly income.

But Duffy and Hensarling got some backup from the testimony of Dale Wilson, the CEO of First State Bank of San Diego in Duvall County, Texas.

"As a result of the QM rules, our bank no longer makes mortgage loans, as the costs and the risks are just too high," Wilson said. He said banks found to have flubbed income calculations could be forced to repay fees and lose the right to foreclose.

Consumer advocates may wonder why a lender that screwed up basic elements of a loan should be allowed to foreclose. But there's a deeper problem with Wilson's claims. His bank can take advantage of the QM perks even if his loans don't meet the criteria. First State Bank of San Diego may have exited the mortgage business, but the CFPB didn't make it.

That's because the QM rule grants a free pass to banks with less than $2 billion in assets in "rural or underserved" areas. Duvall County is classified as a rural or underserved area, and Wilson's bank has just $80 million in assets, according to his testimony.

Wilson's testimony, however, offered Republicans several opportunities to express concern about the recent uptick in small bank mergers. While the GOP offered few critiques of capitalist business combinations in the years leading up to the financial crisis, it has recently become popular for Republicans to claim Dodd-Frank's regulatory burden is forcing small firms to merge with larger institutions. Hensarling and Reps. Shelly Moore Capito (R-W.Va.), Randy Neugebauer (R-Texas) and Blaine Leutkemeyer (R-Mo.) all raised the prospect that regulatory strangulation is forcing mergers.

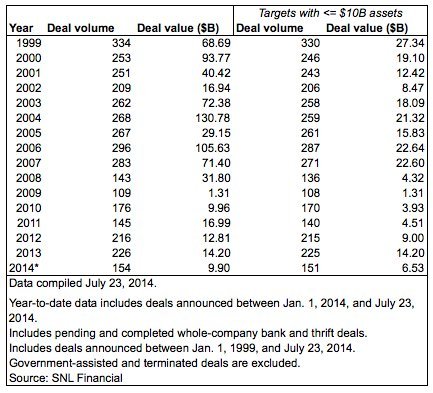

That may be so in some cases, but there's no evidence of a small bank apocalypse. In fact, the pace of small bank takeovers has slowed since Dodd-Frank, according to data from SNL Financial.

In the Bush years leading up to the 2008 crash, acquisitions of banks with $10 billion in assets or less (a common community bank threshold) averaged 255 a year, with a peak of 287 in 2006, and a low of 206 in 2002, according to SNL Financial. In the three full years since Dodd-Frank passed in the summer of 2010, there have been an average of 193 small-bank mergers, with a high of 225 in 2013 and a low of 140 in 2011.

Republicans made the bulk of the outlandish comments at the hearing, but Frank got into hot water for repeatedly claiming that Dodd-Frank had outlawed bailouts of big banks. What he said was technically true -- the law explicitly bars the government from saving a big bank in crisis, and requires its shareholders to be wiped out in what Frank joked were "death panels."

But Rep. Brad Sherman (D-Calif.) argued that the legislative language on too-big-to-fail was a meaningless formality.

"We're told that the current law prohibits using taxpayer money to bail them out," Sherman said. "Well, I was here in 2008. The law prohibited using taxpayer money to bail them out. We passed a law to bail them out."

Sherman argued that banks saw what happened in 2008 and will expect the same treatment in the next crisis. He then blasted Hensarling for not allowing the committee to vote on his bill to break up the big banks..

But most of the hearing was an ideological wrestling match over whether regulation could ever possibly be useful, peppered with partisan jabs.

"There's maybe a push on the other side of the aisle here that there's no need for a Congress, that we simply have an all-powerful executive," Duffy said at one point.

"I gotta be honest, I'm getting tired of the regular hearings that we have simply stating political points over and over," Rep. Mike Capuano (D-Mass.) said. "Barney, did you miss us?"

"No," Frank replied.