Giant kangaroos that roamed the Australian outback 100,000 years ago apparently didn't hop like the roos you see today. But as to how the extinct "sthenurines" got around, scientists weren't quite sure until now.

A new study suggests that the extinct kangaroos had a slow and steady walk.

“When I first saw a specimen at the Australian Museum, it appeared to have an arthritic back and you very rarely see that in wild animals," Dr. Christine Janis, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Brown University and the lead author of a new study about the ancient kangaroos, told The Guardian. "I thought: ‘How could it have that when it was hopping?’ That made me think these guys are not like modern kangaroos at all."

(Story continues below)

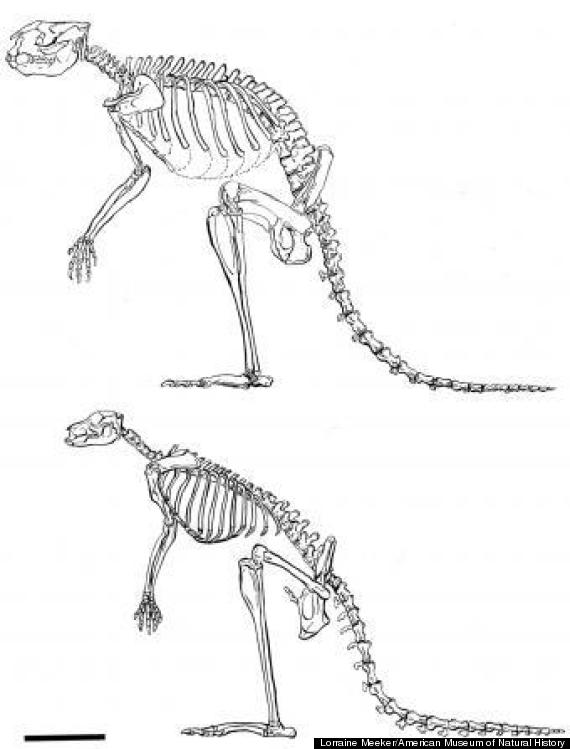

The extinct sthenurine (top) had larger bones, a stiffer spine, and other important differences from modern-day kangaroos (bottom). Scientists say those differences suggest sthenurines walked instead of hopped.

For the study, the researchers analyzed more than 140 kinds of modern and extinct kangaroo and wallaby skeletons, including sthenurines, to figure out how each animal moved.

The sthenurines' anatomy suggests that the animals -- some of which are believed to have weighed as much as 530 pounds -- would have been poor hoppers. Instead, the animals probably shifted their weight from one hind leg to another as they moved rather than moving both legs, as in a hop.

Previous studies dismissed the possibility that the ancient kangaroos got around on all fours, using its tail as well as its four limbs -- what scientists call pentapedal locomotion.

“If it is not possible in terms of biomechanics to hop at very slow speeds, particularly if you are a big animal, and you cannot easily do pentapedal locomotion, then what do you have left?” Janis said in a written statement. “You’ve got to move somehow.”

Still, kangaroo locomotion remains a controversial topic among paleontologists.

"I suspect that the locomotion of sthenurines will continue to be debated," Dr. Natalie Warburton, a senior lecturer of anatomy at Murdoch University in Australia, who was not involved in the new study, told Live Science. "But that is what science is about, proposing hypotheses based on the available evidence and then testing them."

The study was published online in the journal PLoS ONE on October 15, 2014.