VASHON ISLAND, Wash. -- Since arriving from Puerto Rico a year ago, Pedro Alvarez says he has learned a lot about healthy living from other people on this island -- a small, crunchy community a short ferry ride from Seattle. He's embraced kale and root vegetables, for example.

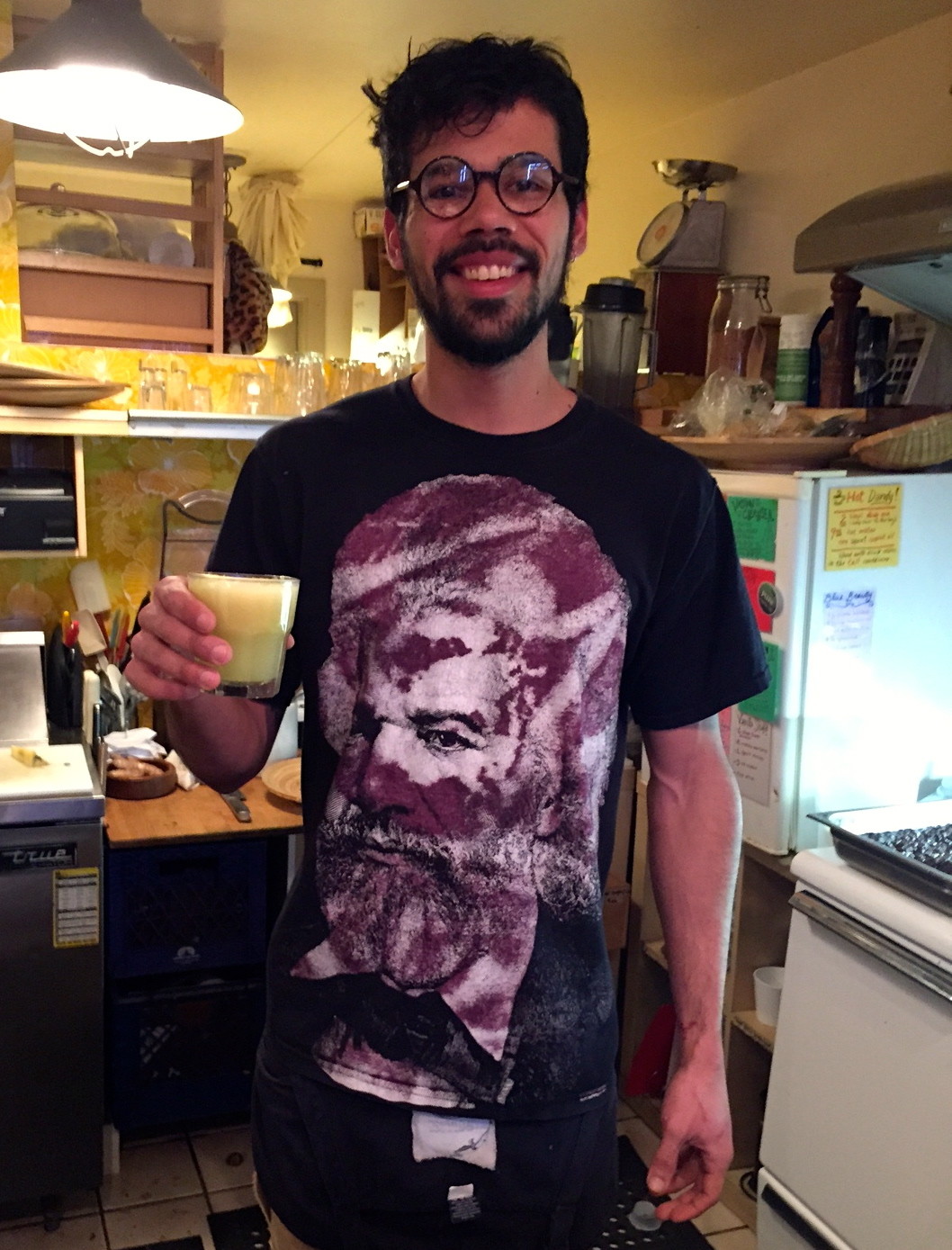

"Vashon is more aware. There are a bunch of really informed people here," said Alvarez, 25, who wore a Karl Marx T-shirt, round-rimmed glasses and trimmed beard as he blended fresh fruits and vegetables behind the bar at the popular Pure Organic Cafe, where he works. He was careful to note these were his personal opinions.

Recently, a neighbor wearing a T-shirt espousing anti-vaccine views caused Alvarez and his girlfriend, who are expecting their first child this month, to question the safety of vaccines. They plan, for the moment, not to immunize their child against communicable diseases like polio, whooping cough and measles.

Vashon Island, a large island in Puget Sound between Seattle and Tacoma, is a bastion of homesteading and do-it-yourself ethos, and perhaps most famous as home to a stronghold of vaccine skeptics. In 2002, a New York Times reporter visited the "counterculture haven" to cover a rising anti-vaccine sentiment. The Times cited resisters' distrust in both the government and pharmaceutical companies as part of an overarching anti-establishment worldview. Not much had changed 10 years later in 2012, when Vashon hosted the Seattle area's highest rate of whooping cough -- for which childhood vaccines are widely available -- during a national outbreak.

Today, a lack of vaccination is still at crisis levels. While fewer than 2 percent of children nationwide have skipped vaccinations, communities with high opt-out rates are scattered across the country, including the liberal enclaves of Berkeley, California, Ashland, Oregon, and Vashon Island.

It's not uncommon on Vashon for the vaccine issue to be discussed as if there were not well-established scientific consensus. "I've heard so many different strong points of view. It's kind of hard to know what to believe," said Stephanie Knoder, 44, the cafe's owner and Alvarez's boss, adding that she had witnessed the "heated debate" over vaccines on her island. "I don't think I've done enough personal research to know what I'd do if I had kids."

A LEGISLATIVE NUDGE

The town's culture isn't the only reason for the dangerously low vaccine rate. State laws are complicit. Washington is one of 20 states that allow exemptions from vaccine requirements based on personal reasons -- in addition to religious or medical reasons -- a policy that more than 90 percent of non-vaccinating Vashon parents have invoked. In light of recent outbreaks, the state also is among a growing number considering measures to revoke the personal exemption.

"We need to think about how our choices affect not just ourselves and own children, but also those we come into contact with in our community," said state Rep. June Robinson (D-Everett), whose bill to remove the personal exemption was approved by a House committee on Feb. 17 and has the support of the Washington State Medical Association and Gov. Jay Inslee (D-Wash.).

Robinson said relatively low immunization rates across the state motivated her to introduce the bill. Seventy-one percent of Washington children ages 19 months to 35 months received all of their shots on time, according to 2013 national immunization data. Nearly 5 percent of children in Washington have not received vaccinations due to medical, religious or personal reasons. Robinson expressed particular concern for the state's anti-vaccination hotspots, such as Bellevue, Arlington and Vashon.

As of last school year, according to data from the King County Department of Public Health, nearly one in four kindergarteners at Vashon's only public elementary school had legally opted out of immunizations for diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, polio, Hepatitis B, and varicella, and measles, mumps and rubella. Most vaccine-wary parents had checked the box labeled "personal/philosophical" on the state exemption form -- much to the chagrin of parents who have opted in.

"We did our homework, too," said Heather Nordlund, as she loaded her 6-week-old son's stroller into the back of her Volvo, parked along the main drag of downtown Vashon. She had taken the 20-minute ferry ride from her home in West Seattle to enjoy the "crunchiness of the island" with her visiting grandmother.

Nordlund said she and her husband first heard about the vaccination controversy from friends in Phoenix, who had decided not to vaccinate their kids. They began digging into the literature themselves and determined that science did not support their friends' concerns. Like the vast majority of other parents in their area, they plan to immunize their son. (West Seattle Elementary School boasts a vaccine exemption rate of 4.5 percent, near the state average, with only about half of those opting out for personal reasons.)

"Anders will be getting his first round of shots at 2 months, but he can't get his first MMR shot until his first birthday," said Nordlund, 38. "I'm a little nervous having him out and about."

For the time being, Anders must rely on the immunity imparted by others around him. In the case of highly infectious measles (about 90 percent of people who are exposed and not immunized will contract the disease), vaccination rates must reach 90 percent to 95 percent in order to protect the entire community -- achieving so-called herd immunity.

Herd immunity protects children who cannot be vaccinated, either because they are too young or, in rare instances, because they suffer from illnesses that leave their immune systems compromised. Newborn babies and sick children also are of particular concern because they are most likely to face severe, life-threatening cases of measles if they are exposed.

The proposed legislation is controversial, even among vaccine experts. "Removing all ability for parents to claim personal belief exemptions is unwise," said Dr. Douglas Opel, a pediatrician at Seattle Children's Hospital and expert in bioethics at the University of Washington. "It could result in backlash, further emboldening those who are against immunization."

As Dr. Saad Omer noted in his New York Times editorial last month, years of protests followed a move by England and Wales in 1853 to make the smallpox vaccine compulsory. A commission eventually exempted those with conscientious objections.

Omer, Opel and others recommend tightening existing laws to nudge, rather than force, parents to immunize their children. Washington state already passed a law in 2011 that requires parents seeking an exemption to first meet with a health care professional to discuss the risks and benefits. But this hurdle may not be high enough, experts said.

To date, no state with a personal exemption option has retracted it. However, in the two states that have never included religious or personal belief exemptions -- Mississippi and West Virginia -- vaccination rates remain exceptionally high. An impressive 99.7 percent of Mississippi kindergarteners are immunized against measles.

"People, for good reason, are worried," said Robinson. "This is all about trying to find a way through policy to keep our kids and communities safe and healthy."

A SHIFT IN FAVOR OF SCIENCE

Legislators are not without like-minded constituents: A growing force of vaccine proponents who live on Vashon Island want to change minds -- an urgent endeavor as measles cases have cropped up in nearby Washington towns over recent weeks as part of a nationwide measles outbreak that has now surpassed 170 cases. "We have overwhelming scientific support for vaccine science, as much as we do for climate change," said Sarah Day, the nurse for the Vashon Island School District. "But here we have some of these same people who believe in climate change who are opposing vaccination."

Views on vaccinations are entrenched. Research published in April found traditional efforts to directly address misinformation, including a debunked vaccine-autism link, didn't work. In some cases, the messages backfired. Experts now say they are desperate to uncover more effective strategies to increase immunization rates.

Celina Yarkin, 47, a mother of three and former vaccine skeptic, has been working with Day to try to convey urgency to fellow parents on the island. She said over tea in the island's bustling Cafe Luna that she believes the actual rate of vaccination exemptions on Vashon is probably higher than what King County estimates. The county survey didn't include home-schooled children.

"Those parents are even more vaccine-hesitant," Yarkin said. "I've learned that a lot about how we make decisions has to do with identity. Once that identity is in place, if it's challenged, then people often dig in further."

That sentiment closely matches the research of Brendan Nyhan, a political scientist at Dartmouth College and lead author of the vaccine-messaging study. He noted his own surprise in finding that none of four pro-vaccination campaigns -- each taking a different persuasive strategy, from facts to emotional stories -- improved parents' intention to vaccinate. In fact, some parents in his survey ended up more rooted in their plan to opt out even when the information campaign successfully corrected the false belief that the mumps, measles, rubella vaccine causes autism. Nyhan and his fellow authors offered one possible explanation: Respondents likely "brought to mind other concerns about vaccines to defend their anti-vaccine attitudes."

"The assumption is often that if you just give people the evidence, then they'll change their mind," Nyhan said. "What we found was disappointing to a lot of people."

Another study, forthcoming from Washington State University, builds on Nyhan's findings: Emotional appeals to vaccinate pushed participants with anti-vaccine views to become even more suspicious of the shots. The authors suggest a better strategy might be to target "core beliefs behind medical skepticism."

Yarkin is currently putting the finishing touches on this year's poster display for the elementary school. Each of the past few years, she's presented basic information concerning vaccines as well as the island's vaccination rates. This time, in addition to the facts and numbers, she plans to include tools that relate to identity: pictures of local families with personal stories of why they chose to vaccinate.

WHAT WE CAN DO NOW

Robinson noted that it will likely be a "long path" toward any new legislation. But momentum is building, and she said the measles outbreak has brought the issue into "sharper focus."

Day, the school nurse, also is optimistic that the current measles outbreak could have a silver lining. Part of the resistance to vaccines, she and other public health specialists suggested, may actually result from the success of vaccinations. Once-deadly infectious diseases have been out of sight and out of mind for decades, lulling people into a false sense of security.

The 2012 whooping cough outbreak may be behind a recent uptick in vaccinations for that disease. And at least the community is talking about measles.

"We all know each other here. People need to know what the implications are for their neighbors," said Day. "Who doesn't know a pregnant woman, infant, or a child with asthma or severe allergies?"

Short of that, efforts to educate are often left to peers -- or doctors. Opel has found that how doctors begin a vaccine discussion with parents can strongly steer decisions.

In one study, when a doctor began with the recommendation a child was due for a certain vaccine, and then paused for the parent's reaction, Opel observed far less resistance than if the doctor began with an open-ended question.

Still, if a parent does have an opinion or questions, Opel said, "it is inappropriate to close off discussion."

Instead, he emphasized, it's important to respect and acknowledge concerns, and understand the source of that hesitation.

"Parents are really just trying to do what they feel is in the best interest of their child," Opel said. "They want to be well-informed. They are in search of the truth."

Clarification: Language has been changed to more accurately describe the location of Vashon Island in Puget Sound.