This weekend brought some good news for people who like to hear about the outbreaks of deadly diseases being curbed.

According to the World Health Organization, Liberia, one of the West African nations that was heavily affected by the most recent outbreak of the Ebola virus, was "declared ... free of Ebola on Saturday, making it the first of the three hardest-hit West African countries to bring a formal end to the epidemic," The New York Times reported.

As The Times goes on to report:

“The outbreak of Ebola virus disease in Liberia is over,” the W.H.O. said in a statement read by Dr. Alex Gasasira, the group’s representative to Liberia, in a packed conference room at the emergency command center in Monrovia, the capital.

Just before Dr. Gasasira’s statement, Luke Bawo, an epidemiologist, showed a map depicting all of Liberia in green with the number 42 superimposed on it. This represented that two maximum incubation periods of the virus, a total of 42 days, had passed since the safe burial of the last person confirmed to have had Ebola in the country, fulfilling the official criteria for concluding that human-to-human transmission of the virus has ended.

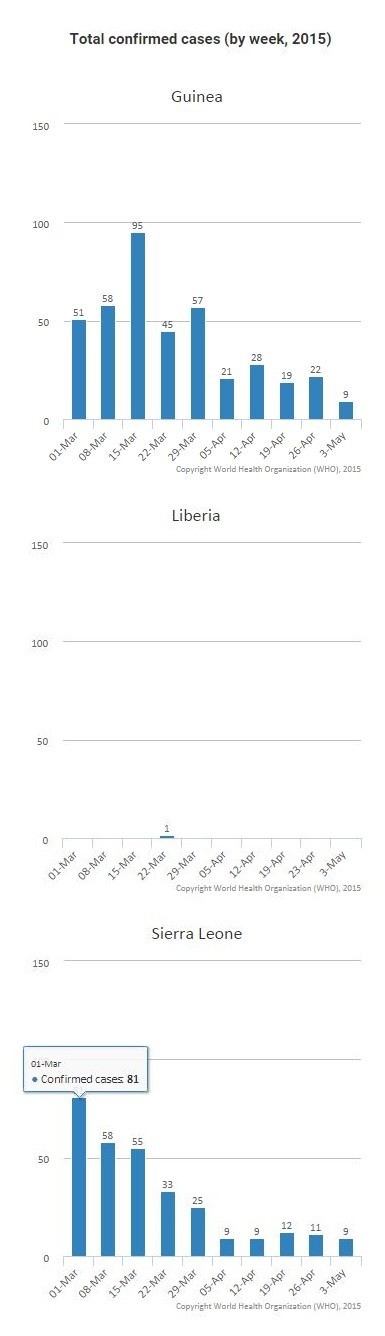

Elsewhere in West Africa, while not yet "Ebola free," Sierra Leone and Guinea are also reporting substantially fewer new cases of the disease, compared to peaks in March of this year.

Those who have been diligently fighting the outbreak in West Africa -- which was briefly brought to our shores at the end of September 2014, can chalk up a hard-fought victory over a scary disease in one of the most difficult environments on the planet. And there's a lot for those who observed this outbreak from the sidelines to celebrate as well.

But on a long enough timeline, the chances of an Ebola resurgence in West Africa remain. The next time it does, however, hopefully we'll be better armed with knowledge that stayed perplexingly elusive this time around:

Better know a virus! When it comes to being cinematically terrifying, it's hard to beat the Ebola virus. It has a high fatality rate, and the death is typically brutal: high fevers, vomiting, diarrhea, organ failure, and bleeding -- internally and externally -- are the norm. So the disease looms in our imagination as something of a holy terror that shreds and liquefies the body of those unfortunate to be infected by it.

But for all its mythic power, the Ebola virus is actually quite a frail beast. It spreads merely through the direct contact with bodily fluids of those stricken -- blood, vomit, and feces primarily. But it's not an airborne disease, and with competent contact tracing and containment, it's not hard to bring an outbreak to heel. Ebola thrives in areas that face grinding poverty, where access to medical care is nearly impossible to come by, community communication infrastructure is weak, and basic sanitation is absent.

During our brief flirtation with Ebola, there were many instances in which people lost sight of this and panicked in embarrassing fashion. For instance, in October 2014, a Maine school board forced a teacher to take a three-week leave of absence simply because she traveled to Dallas while that city was playing host to Ebola patients. It mattered not a whit that the teacher never came within ten miles of the hospital where those patients were treated -- irrational fear was the order of the day. It's important for us now to simply say: These people were stupid.

And that's really the only way Ebola could possibly break out wide into the public -- stupidity. So let's inoculate that as best we can. (And yes, that means the CDC will have to tighten its game a little bit as well, and avoid the few mistakes they made.)

Recognize the advantages the United States has. The United States is rather uniquely positioned to contain an Ebola outbreak, so it's hardly surprising that we managed to do so -- the disease of our dread imaginings brought down by basic infrastructural and economic realities.

Should the U.S. play host to another Ebola outbreak in the future, it will be important to remember how swiftly and effectively the last one was put down. But it will also be important to remember that keeping Ebola out of the United States will require strangling the recent outbreak at its source, West Africa. To repurpose a shop-worn war-on-terror cliche: If we fight it there, we don't have to fight it here. If we forsake that effort, we assume the risk of it finding its way to the States again.

And we'd probably be better off knowing Africa a little bit better as well. It's a huge continent. It's possible to travel thousands of miles within Africa. So if a person goes to, say, Zambia, and then returns to the United States, it's not smart to panic about whether that person returned with Ebola. Africa is not a monolith, and the things that might be happening in Sierra Leone aren't necessarily the things that are happening in Botswana.

For American politicians, heavy-handed is not the way to go. Whether it was the heightened likelihood of nonsense behavior that any election year brings, or whether some politicians are just naturally predisposed to making poor decisions, America's Ebola outbreak managed to bring out some of the worst in our policymakers. From exaggerated claims about undocumented immigrants or terrorists bringing Ebola over the Mexican border (we should be so lucky as to have terrorists who only operationalize zany and over-complicated plots) to the widespread calls for travel bans to and from the affected area in West Africa (a great way of worsening the crisis), something was deeply amiss in the brainpans of many of our elected leaders.

Wherever a heavy hand was laid, pointless difficulties arose. A handful of governors -- New Jersey's Chris Christie, New York's Andrew Cuomo and Maine's Paul LePage -- decided that they just had to invent their own weird quarantine protocols and force them upon members of the medical community, a move that did no good for anyone and only fostered meaningless confrontations. Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal took things a step further by asking some of the world's top minds on Ebola to stay out of his state and not attend a scheduled conference of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene -- a move that probably had Brown University reconsidering whether Jindal deserved the biology degree they'd conferred upon him.

The better strategy was to let calm and cool heads prevail, something that President Barack Obama was well-suited to implement. Dismissing the calls to impose dramatic travel bans and constantly supporting the work of the medical professionals tasked by the government to preside over public health crises, Obama projected steadiness while keeping out of the way of the people doing the work. Needing to check off the "DO A THING OMG" box, Obama appointed Ron Klain to be America's "Ebola Czar," and then Klain did what the job demanded: keeping the White House out of hot, hyped headlines. (Obama's decision to demonstrate his confidence in the people tending to the outbreak by meeting with them personally -- even shaking the hands and hugging those who were exposed -- was a nice touch.)

And while there were some moments where he veered slightly into the wrong lane, then-Texas Gov. Rick Perry succeeded in getting out on the right foot when Ebola came to Texas. "This is all hands on deck," said Perry. "We understand that and we've got great local partners. Everyone has their marching orders and understands the importance of that good collaboration." In the space of a few sentences, the oft-maligned Perry communicated everything essential -- he projected a sense of mission, he emphasized the competence of the major players and he offered a sense of certain optimism.

All of which suggests that the ideal rubric for politicians when it comes to responding to a public heath crisis is: stay calm, don't get clever and don't feed fear. Basically, if you're the sort of politician that imagines that the military's Jade Helm 15 exercises are a super-secret plan to take over Texas, you aren't well-suited to lead in an Ebola crisis. (Looking at you, new Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, who Perry has already criticized for this precise overreaction.)

For the media, reach out to experts and deny airtime to the cranks. I've written extensively already on the media's particular failings in covering the Ebola outbreak, as well as those who served as exceptions to the (mis)rule. So I won't repeat myself. And neither should the media -- they should have already done some extensive soul-searching about the botch job they perpetrated on the public.

The good news, of course, is that now Liberia has passed a test that Nigeria, Mali, Senegal, Spain, the United States and the United Kingdom have already aced -- the successful conquering of an Ebola outbreak. That means that should an outbreak flare up again, the media can turn to the heroes of this last one as their sources, and use that deep well of calm, confident expertise to help shape the coverage. All of the cranks and yokels and con artists who led the media in a pitched, irrational frenzy can be kicked to the curb, in lieu of those who actually went out and got the job done.

Pay attention to the road ahead. As great as it is to see Liberia conquer this Ebola outbreak, how well it handles the next one is going to depend heavily on what lessons are learned and how quickly systemic change happens -- economic assistance, better and more sustainable hygiene practices, health care system development and political stability will all play a role.

As Karin Landgren, the United Nations' special representative of the secretary-general in Liberia, told the U.N. Security Council last week, “Now is the time to address factors which contributed to Ebola’s spread, in particular, weak social service delivery, lack of accountability and overly centralized government.”

She outlined the vulnerability of Liberia’s extractives-based, enclave economy to sharp drops in commodity prices and efforts to strengthen the economy, as well as steps to push through a security transition and measures to combat corruption.

[...]

She also pointed to “long-standing societal divisions” that were as yet not healed after years of conflict and which threatened to deepen during the Ebola outbreak, noting the Secretary-General’s call for justice and addressing of past violations to secure a stable future, and stating that “national dialogue about social exclusion, and about the crimes of the past, remains muted at best.”

As The Times reported Monday, Liberia will have to deepen and sustain the health practices adopted during the outbreak, as well as act on fixing many of the systemic problems with health care delivery. In an email to The New York Times, Liberia's health minister, Dr. Bernice Dahn, wrote, “We are being extremely cautious... Ebola highlighted our health system’s weaknesses."

Be glad! Look, we don't often get a chance to say this, but in the case of the West African Ebola outbreak, the good guys are winning, and lots of people who might have otherwise perished are alive today. So don't forsake the opportunity to just be happy about this. With calls for sustained "vigilance" emanating from Liberia's president and the World Health Organization, hopefully this will be some good news that persists a long while.

Would you like to follow me on Twitter? Because why not?