Edouard Manet's "Olympia" scandalized nearly everyone when it was first exhibited at the 1865 Paris Salon, its nude subject confronting the viewer with an unflinching gaze and brazen sexuality. Francisco Goya's Nude Maja, created over half of a century earlier, was similarly shocking, both because of the model's visible pubic hair and palpable lack of shame.

A third equally heretical and pivotal nude painting, however, is often erased from the conversation: American artist Romaine Brooks' 1910 "White Azaleas." The image depicts a sensual female form stretched out amidst Brooks' own domestic space. (It should be noted that the arena of desire is not in a brothel or an exotic destination, but in the home.) Instead of staring head-on at the viewer, the subject averts her eyes, not out of disgrace or modesty, but due to what feels like aversion.

What makes this bare odalisque stand out from the others rendered by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, François Boucher, Gustave Léonard de Jonghe and others? In short, it was painted by a woman.

Left: Edouard Manet, Olympia. Right: Romaine Brooks, White Azaleas (1910)

Romaine Brooks, whose given name is Beatrice Romaine Goddard, was born to two wealthy American parents in 1874. Her father deserted their family early on, leaving her mother Ella to care for Beatrice and her brother Henry. Brooks endured a painful childhood, riddled with physical and mental abuse from her mother, who reportedly suffered from "exacting and autocratic madness." Among other vindictive measures, Ella forbid Brooks from drawing.

Despite her mother's veto, Brooks created art in secret. "Finding no outlet for my imagination, I used to chalk on the blackboard, when I was alone," Brooks wrote in her unpublished memoir, No Happy Memories. As her book's title implies, Brooks' childhood was characterized by pain. At the age of seven, Brooks' mother sent her to live with the family laundress in a New York tenement while she accompanied Henry, diagnosed with mental illness, on doctors' appointments in Europe. Brooks was then sent to an Episcopal school and, subsequently, a convent in Italy.

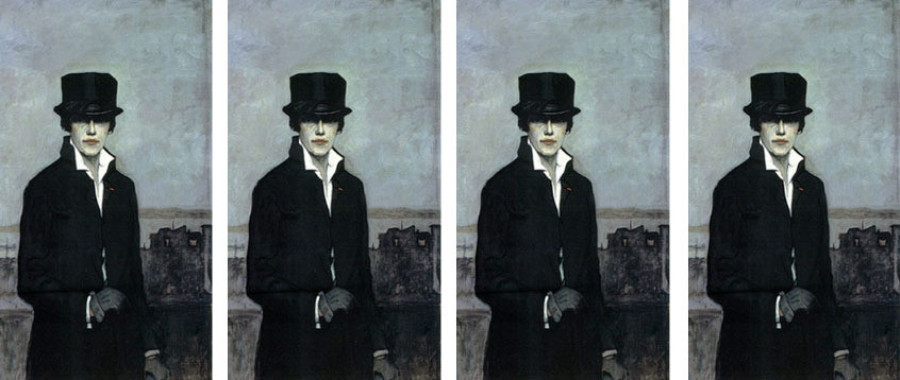

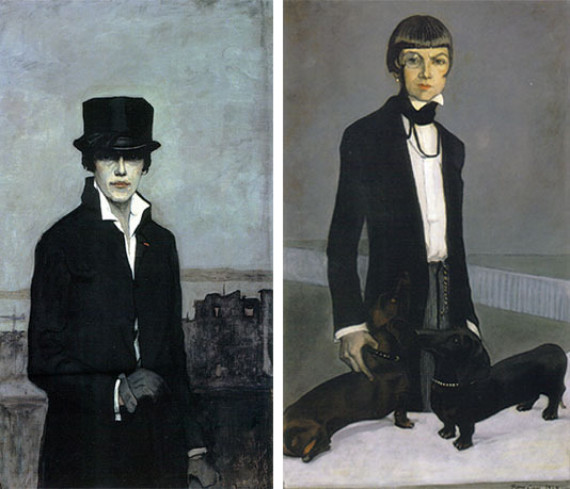

Left: Self-Portrait (1923) Right: Una, Lady Troubridge (1924)

At 19 she moved to Paris and at the age of 21, Brooks moved to Rome to study art at Scuola Nazionale and Circolo Artistico -- where she was inexplicably the only woman at a men's school. During this time, Brooks faced a great deal of sexual discrimination and harassment. In one incident, a fellow student in her life drawing class left a book open by her workspace with pornographic excerpts highlighted. Brooks responded by hitting the offender in his face with the book.

As you've likely inferred, Brooks wasn't all too concerned with conforming to the mainstream expectations of women at the time. She took up with an artistic counterculture, upper-class Europeans and American expatriates, many of whom were creative, bohemian and gay.

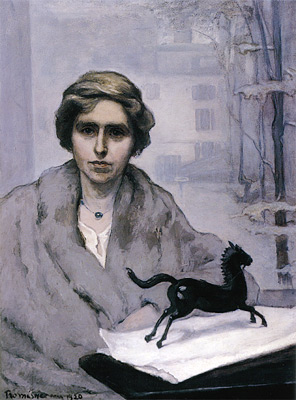

Miss Natalie Barney, "L'Amazone" (1920)

In 1901, Brooks' brother passed away, followed shortly by her mother. Brooks inherited her family's fortune and, with her newfound financial independence, relocated to Paris. She soon wed her close male friend, a gay pianist named John Ellington Brooks. Although her reasons for marrying Brooks remain widely unknown, biographer Meryle Secrest hypothesized the artist was looking for companionship and was concerned for her future husband's financial wellbeing. She also was happy to take the new name, leaving her dysfunctional family behind.

The partnership was short lived. Part of the impetus behind the split was John Brooks' disapproval of Romaine Brooks' short haircut and masculine style. When he attempted to censure his wife's renegade style, she became disgusted with his desire to conform to societal norms.

Left:James MacNeill Whistler, At the Piano (1858–1859), Right: Romaine Brooks, Renata Borgatti at the Piano (1920)

It was around this time that Brooks was first introduced to the work of James Abbott McNeill Whistler, the American-born, British-based artist who would go on to inform her iconically muted palette. Brooks was captivated by Whistler's hushed gray-centric tones, punctuated by the occasional streak of umber. She took on a similar set of shades herself, detaching herself from the wild and colorful shades found in Fauvism, the dominant movement of the moment.

In 1910 Brooks was invited to debut a series of her paintings in Paris. The standout piece was the aforementioned "White Azealeas," a portrait of Brooks' short-term lover and long-term muse, Ida Rubinstein. Brooks was enchanted with Rubinstein's angular and pale aesthetic, "finding in her thin, lithe figure the living incarnation of her own artistic ideal."

La France Croisée (The Cross of France, 1914)

Despite her obsession with Rubinstein's beauty, Brooks' most extended and passionate relationship was with Natalie Barney, an American-born writer who held a Sapphic literary salon in Paris' Left Bank. The two were together for fifty years. Brooks was heavily influenced by Barney's combination of radical ideas and traditional forms, yielding figurative paintings of heroines, at once revolutionary in their feminism and aesthetically at home in the history of Western art. Brooks often referred to Barney as an Amazon -- a feminine warrior operating in a sphere outside of male influence.

Natalie Barney and Romaine Brooks, circa 1915, via Wiki Commons

Throughout her career, Brooks painted women, and in doing so, molded a new shape for the 21st century lesbian -- sometimes sexual, sometimes not, sometime masculine, sometimes feminine, and not really all too concerned about your prognosis. Her subjects are characters, not fantasies, yet almost Cindy Sherman-esque in their ability to shape-shift and warp their identities and roles. The gray-toned depictions didn't just document lesbians of the time, they forged a strong yet malleable image for lesbians and transgressive women of future generations.

In 2000, art critic Holland Cotter summed it up when describing Brooks' 1923 self portrait: "One of the points of the picture is that she's watching you before you get close enough to look at her," he said. "She's not passively inviting your approach; she's deciding whether you're worth bothering with. Chances are, you're not, at least not if you're approaching with the conventional notions of what male and female mean."

Today, the slipperiness of sexual orientation and gender identity -- and identity in general -- often pops up in relevant contemporary art. However, during Brooks' lifetime, the fact that a woman could be the object of female desire, or that she could be completely uninterested in being the object of male desire, was rarely visualized or communicated. Brooks changed that -- and, with those same brushstrokes, helped to change the history of art and gender equality.