I am the lone juror who voted not guilty in the Etan Patz case. As the re-trial of Mr. Hernandez will commence next September, I am launching a series of blogs that offer my inside perspective on the original trial and deliberations. My first blog focuses on Mr. Hernandez's confession which was at the heart of my decision to vote not guilty. Future blogs will address how and why the police could have crafted the story in advance, Etan's real murderer, mental health, the importance of reasonable doubt, the weakness of memory, and the role of eyewitness misidentification.

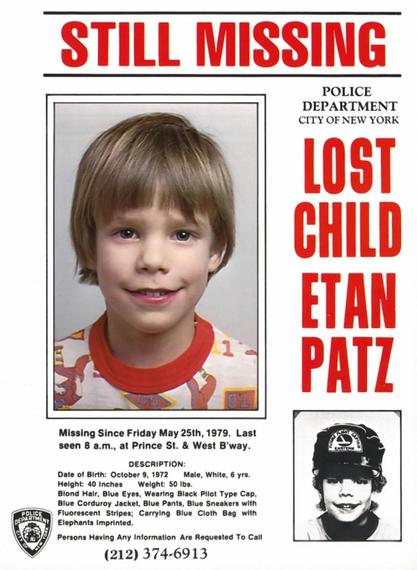

False confessions are under a lot of scrutiny lately thanks in large part to the media coverage of the Central Park Five settlement, efforts by the Innocence Project, and recent documentary, Making a Murderer. This is a good thing. A possible false confession played a pivotal role in my decision to vote not guilty in the Etan Patz kidnapping and murder trial against Pedro Hernandez last year. For New Yorkers, the name Etan Patz is synonymous with the first picture of a missing child on milk cartons and the loss of America's innocence that led to helicopter parenting nationwide.

If you are not from New York city, here is a brief summary of the facts that are known for sure about what happened in 1979. Etan Patz, a precocious and extremely kind six-year old boy, left his apartment in Soho a little before 8 a.m. to go to school. His mother, Julie, accompanied him to the corner of Wooster and Prince Streets. He insisted on walking the rest of the way to the bus stop by himself -- a mere one and a half blocks away. Julie gave in and allowed Etan to walk alone the rest of the way to his bus stop. By 4 p.m., Etan had not returned from school. Julie became worried and called the police. Two detectives arrived by 4:30 p.m. and an intensive search of the neighborhood was launched by 6 p.m. that night. For weeks, dozens of police and many more neighbors and friends searched buildings, alleys, rooftops, and streets looking for Etan. But he was never found and to this day, no body or physical evidence has been recovered. Somehow, within that block and a half, Etan disappeared forever.

Fast forward to April, 2012, when the New York Police Department (NYPD) received an anonymous call from a person who claimed to have information about Etan's disappearance. Detectives eventually got the informant to say who he was and within an hour they were at his door questioning him. It turns out it was Mr. Hernandez's estranged brother-in-law. Over the following weeks, the police researched the background of the suspect, learning about his low intelligence, fervent religious beliefs, Puerto Rican heritage, poor understanding of English, and decades long struggle with mental health problems and physical pain. What they did not find was any history of violence or criminal record.

At 4 a.m. on Saturday May 23rd, 2012, more than twelve NYPD detectives and Assistant District Attorneys (ADAs) drove 2 hours to Maple Shade, New Jersey where they picked up Mr. Hernandez at his home at 7:30 a.m. and took him in for questioning.

While inviting Mr. Hernandez to the Camden County Prosecutor's Office, the detectives took away his wallet, cell phone, and pain medications. The police could not arrest Mr. Hernandez because they had no evidence to justify a warrant. So they counted on Mr. Hernandez's complete cooperation -- which is what they got.

Questioning started at about 8 a.m. In a small windowless cell named "Lock-Up 133" three detectives took turns questioning Mr. Hernandez while he sat in a corner. The police admitted in court that they began with the basics, asking questions about his childhood growing up on a farm in Puerto Rico and his deeply held Christian beliefs. They wanted to build a rapport and trust with Mr. Hernandez. Questions soon turned to the beatings he received from his alcoholic father and his ugly divorce with his first wife, Daisy. By about 9 a.m., detectives walked Daisy past Lock-Up 133, making sure that Mr. Hernandez saw her. When asked if he recognized who she was, Mr. Hernandez immediately asked why she was there and if this questioning was related to one of the many times that Daisy filed frivolous petitions against him about child support for their two children. The police said, "no, this is about something much more serious."

By 9:30 a.m. the detectives pulled out the Missing Poster for Etan Patz and showed it to Mr. Hernandez. They asked him repeatedly if he knew the boy or his family. They accused him of killing Etan. They told him that Daisy was saying that he had admitted to killing a child in New York City before they got married. Detectives then told Mr. Hernandez that Etan could go to heaven if he confessed. They said Etan would finally have peace. They told him that he could go home if he just told them what they already knew. But Mr. Hernandez denied the accusations. On three occasions Mr. Hernandez asked if he could go home. Each time, detectives said he could go after he answered a few more questions. What Mr. Hernandez did not know was that he could have walked out at anytime he wished since he was not formally in custody yet. By 2:30 p.m., it was too much for Mr. Hernandez. He confessed to "choking the boy" and leaving him alive -- never naming Etan or saying that he killed him. Immediately after this strange confession, he asked if he could go home to his wife and daughter.

But now you will hear the most important part of the story. Although it is required by New Jersey state law to video record all criminal suspect interrogations, New York ADA Durastante, told his Camden County colleagues not to turn on the camera until Mr. Hernandez was ready to be read his rights. This decision implicitly meant that there would be no video evidence of the police interrogation until the moment when Mr. Hernandez was prepared to confess and placed under arrest.

As jurors, we felt duped. When we heard ADA Durastante's reason for not switching on the camera most of us felt like he was not telling the truth. He said he felt it would be "disruptive to the process". However, we learned that the camera was mounted discretely in a smoke detector in Lock-Up 133 and could be activated remotely so no one would ever notice it being switched on.

This was a real problem for me and most of the jurors. Seven out of eight hours of the interrogation were not recorded and the police had no reasonable justification for it. Especially for a case as important as this and in a time when cameras are ubiquitous and easy to operate.

As jurors we had the right and the duty to weigh all of the evidence in order to make a fair decision about a person's freedom and bring justice to a suffering family. We needed to see the full interrogation to determine if the story Mr. Hernandez eventually told police originated with him or if it was coached to him by the detectives.

Although authorities are allowed to lie about evidence and witnesses to get a person to confess, I feel people, especially jurors, often overlook the very real possibility that these deceptive tactics can also get an innocent person to confess to something they did not do. This is especially true for more vulnerable people like Mr. Hernandez who is not intelligent (he has a 70 IQ), has poor memory for details, and has a history of mental illness. Add to this the fact that his comprehension of English is weak and he was being questioned without a lawyer and one can start to imagine how Mr. Hernandez could be coached into a confession -- a phenomenon Dr. Saul Kassin, one of the nation's prominent experts on confession evidence, calls "coerced-internalized false confessions", where individuals actually come to believe in their own guilt as a function of police deception and the person's own suggestibility.

And there is a growing body of evidence that false confessions happen more often than people think. The Innocence Project has helped to exonerate 94 wrongly convicted people who initially confessed to crimes they never committed. These innocent people spent a combined 1,423 years in prison and in 28 of these cases, the real perpetrator was never apprehended and may have committed more crimes.

Because law enforcement did not record their entire interview with Mr. Hernandez on video we will never know if the initial confession was genuine or if it was a story that was coaxed from him under extreme emotional, physical, and spiritual duress. Without any physical evidence connecting Mr. Hernandez to the crime and nothing to corroborate the stories told to police by five witnesses, the police knew they would never have enough evidence to bring a case against him without a confession. In Mr. Hernandez, they found the perfect scapegoat.

I would like to request that the NY District Attorney's office release all of the confession videos of Pedro Hernandez online to allow the public to make their own decision about their authenticity.

My next blog will discuss where "the confession story" came from and how the police could have had it first.