Illegal immigration remains a hotly contested issue within the United States, as evidenced by the subject's repeated appearance in American political discourse over the years. As Ambassador to Mexico from 1998 to 2002, Jeffrey Davidow experienced firsthand the hardships of managing this complex issue. During his tenure, Davidow struggled to resolve immigration problems with the frequently hostile government in Mexico City and to convince his hosts that his embassy was operating with good intentions. He was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy in 2012.

You can read other Moments on consular issues. "To Mexicans, we are both a threat and an opportunity"

DAVIDOW: I was there from 1998 to 2002, which was a very interesting period, because it was the last two years of the Clinton administration, and also the last two years of the PRI [Institutional Revolutionary Party] domination of the presidency in Mexico. And then we had two new presidents come in, [Vicente] Fox and [George W.] Bush.

So my stay there was pretty much divided in half as I dealt with four presidents and a very changed political situation....

The relationship with Mexico was and still remains an extraordinarily complicated one. It is subject to periods of real friction and then things get better for a while, then the friction returns. The Mexicans have an attitude towards the United States which is often described as love/hate.

I don't agree with that. It is not love/hate. There's very little love and there's very little hate. It's just that to Mexicans, we are both a threat and an opportunity. We're a threat because our culture threatens to overwhelm them. Our economy and our political weight in the world is disproportionate to theirs.

But we're a great opportunity as well, for trade, for immigration, for culture. So there's always an ambivalence in Mexico. In the United States, generally we don't pay much attention. And of course that's the greatest insult of all to somebody, when you don't pay attention to them....

"The domestic political advisors were telling the President that he could not do anything on immigration. And so the process went nowhere."

In July 2000 Fox won the [Mexican presidential] election, and the PRI moved out of national power over the next few months. We went into a period of intense activity because we had a new president in Mexico, Fox, and a new president of the United States, George Bush, by the beginning of 2001.

Now, for Bush, who was not at all experienced in international relations, Mexico was a country with which he already felt some affinity. Many Texan politicians, because they've grown up near the border and have probably had a Mexican cook making them tortillas, have a sense that there is a special relationship with Mexico.

And so, Bush very early on in the first month of office decided that he wanted to get together with Vicente Fox. It was billed as the "Meeting of the Two Cowboys."

In point of fact, Fox has a vegetable ranch. He's really not a cowboy and neither is Bush. But the idea was that these were two guys with similar backgrounds from the border who could reach agreements and build a new relationship. And President Bush was really excited about this. So within six or seven weeks of becoming president, they met at Fox's farm....

Now, there were many issues, and no sense getting into them all, but the really big question that dominated the meeting, and then much of the rest of Fox's presidency, was, of course, immigration.

Now, the White House understood this to be a politically sensitive topic in the U.S. And indeed, before they even made the trip, Condoleezza Rice, the National Security Advisor, told the press that, "We're not talking about amnesty," meaning we're not going to consider how to make those 12 million or so undocumented aliens in the United States legal residents. The political fallout of that for the Republicans was judged to be too great.

At the meeting, Bush and Fox agreed that they would form a high-level committee headed on our side by Secretary [of State Colin] Powell and Attorney General [John] Ashcroft and on the Mexican side by Foreign Minister [Jorge] Castañeda and another high official. They would come up with a plan to deal with immigration before June 2001. In other words, they had a three- or four-month deadline. There were a lot of subsequent meetings, mostly at the level of officials.

But it became apparent to me that, at the time, there was no way around the political opposition that was, we heard, coming from [Senior Advisor to the President] Karl Rove and the domestic political advisors who were telling the President that he really could not do anything on immigration and should wait until at least after the midterm elections of 2002. And so the process went nowhere.

Meanwhile, the Mexicans were arguing strongly for a comprehensive immigration agreement that would not only legalize people who were in the U.S., but make it easier for others to come in.

What the Mexicans never truly understood was that this really wasn't a negotiation because the decisions on immigration were totally in the hands of the United States, and there was little or nothing Mexico could offer in return. (The Mexican Government was certainly not politically able to try to stem the flow of emigration.) So there was a lot of activity, a lot of press, a lot of recrimination.

And here we are a dozen years later, and the situation has not changed in any appreciable way. In fact it has gotten worse because it was not attended to. And, of course, after 9/11, there wasn't any chance at all. It was a moment of lost opportunity.

In some ways I think both Bush and Fox were naïve at the very beginning. They felt they could find more common ground and bring their respective populations along with them. But they really could not. And you're right that Mexican politicians should be more understanding. There had already been some important changes in the ways that Mexicans looked at emigration.

Although the PRI would periodically complain about the way Mexican migrants were being treated in the States, the general attitude of previous Mexican governments had not been one of great concern. From their point of view, Mexicans living in the States had made the decision to leave and were really no longer their problem. In point of fact, most Mexican politicians looked on immigration to the U.S. as a safety valve, eliminating from Mexico a lot of people who were obviously unhappy with their situation there.

Fox changed that. He started referring to Mexican migrants as heroes, people who really represented the best of Mexico. And he felt that he had to push hard for a full comprehensive settlement. But the U.S. side was not ready ... to deal with the amnesty/legalization issue...."I tried to explain the reality, but without much success and absolutely no sympathy for our position from the Mexicans" The situation, which was bad, was made worse by press and politicians who would continually distort reality. I think many Mexicans felt that there was a conscious policy on the part of the United States to mistreat the Mexicans in the U.S. So every time there was an incident or a killing along the border, this would become a cause célèbre in Mexico.

The situation, which was bad, was made worse by press and politicians who would continually distort reality. I think many Mexicans felt that there was a conscious policy on the part of the United States to mistreat the Mexicans in the U.S. So every time there was an incident or a killing along the border, this would become a cause célèbre in Mexico.

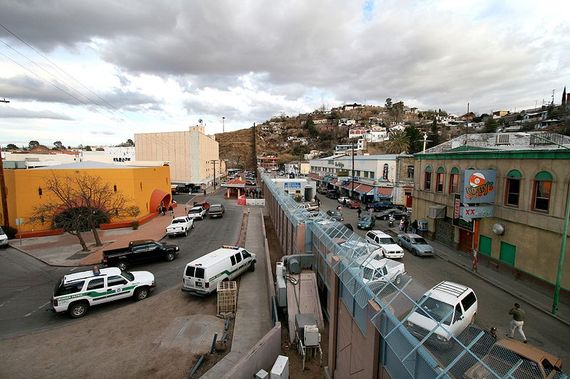

At one point there were groups of vigilantes on the U.S. side who would go out and "hunt" migrants, that is, they would patrol the border, stop people who were obviously crossing illegally and turn them over to the border patrol. (Pictured: Nogales border crossing)

What I didn't understand for some time was that most Mexicans, when they read the headlines about hunting migrants, actually thought that there were people on the U.S. side taking their guns and going out and shooting people. I tried to explain the reality, but without much success and absolutely no sympathy for our position from the Mexicans.

But it was hard to defend against the Mexican argument, which is essentially that these people would not go to the United States if our system did not welcome them with jobs. And in point of fact, ... they are correct. The argument is a variation on the one used to deny responsibility for the drug trade -- if you people stopped using drugs, we wouldn't be sending them north.

As the jobs have disappeared in the U.S. in recent years, migration from Mexico has gone to a point where today there is actually a net zero flow. As many people are going back to Mexico as are coming in from Mexico. I think this is a function of our lousy economy, but many experts argue that the economic development within Mexico is making emigration from there unnecessary. We'll see what happens when our economy recovers.

I think you may be right in saying that the Mexicans don't understand our position. But we really don't understand theirs either....

In Washington, once it became apparent that there wasn't going to be a global resolution, I continued to push for small steps that could have made life better for large numbers of Mexicans already in the United States. And at times, even the Mexican government rejected those small steps because they wanted to keep the pressure up.

I'll give you a specific example. At one point, Congress was faced with the possibility of approving a piece of legislation that would allow Mexicans already in the U.S., and who had already received approval or notice that they were going to get a green card, to not have to go back to Mexico for their interview at a consulate. Many did not want to take the risk of leaving the country, so they chose to live in illegality. The new law would let them change status in the U.S. And this would have helped half a million Mexicans.

But the Mexican government put the word out on the Hill to friendly Democrats ... that they did not want to see this happen because it would take the pressure off the larger issue. Bush found out about that and he was totally steamed. But there was no meeting of the minds really. There was a lot of talk about how we have to solve this problem, but very little was done.