Chilean Sea Bass is a Sea Bass From Chile

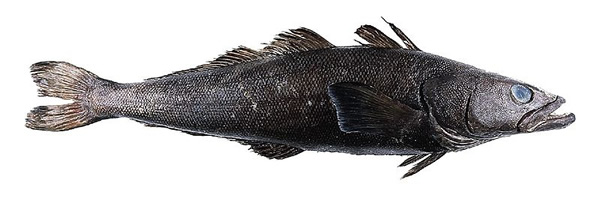

Chilean sea bass sounds quite nice, doesn't it? That's exactly why it's called that instead of the fish's real name: Patagonian toothfish (man, what an ugly fish!)

Patagonian toothfish a.k.a Chilean sea bass. Image: Wikipedia

In 1977, a fish wholesaler named Lee Lantz wanted to sell Patagonian toothfish to the American market, but realized that nobody wanted to eat a fish with such an unappetizing name. So he tried "Pacific sea bass" and "South American sea bass" before settling on "Chilean sea bass."

The clever name isn't the only problem with Chilean sea bass: according a 2011 DNA analysis by Peter Marko of Clemson University, 15 percent of Chilean sea bass sold with eco-labels weren't actually from approved, the sustainable stock. Worse, eight percent were actually different species of fish altogether!

The First Caesar Salad Was Made From Scraps

From its name, you'd think that Caesar salad is a salad fit for Roman emperors, but did you know that the first Caesar salad was made from scraps?

From its name, you'd think that Caesar salad is a salad fit for Roman emperors, but did you know that the first Caesar salad was made from scraps?

In 1924, chef Caesar Cardini (yes, the salad was named after him), ran out of food in his restaurant's kitchen, so when a customer asked for a salad, he made do. Cardini put together bits of lettuce with olive oil, lemon juice, Worcestershire sauce, egg, garlic, croutons and Parmesan. He then added the dramatic flair of tossing the salad "by the chef" at the table-side. The crowds loved it, and the Caesar salad was born! (Image: Wikipedia)

Two Words: Meat Glue

If you thought pink slime in your burger was bad, wait till you hear about meat glue in your steak.

Meat glue, or an enzyme called transglutaminase, binds protein together. It is often used in the food industry to stick together scraps of meat into prime cuts of steak. After the meat is cooked, you can't tell the difference.

Granted, not all restaurants resort to this cheap trick, but the practice is probably more pervasive than you'd think.

You Won't Find Fortune Cookies in China

Eat in any Chinese restaurant in America, and you'll be served with a plate of fortune cookies at the end of the meal. Fortune cookies are so quintessentially Chinese ... yet you won't find them in China.

The origin of the fortune cookies is controversial, but food researchers pointed to its origin as distinctly Japanese (the modern version of the fortune cookie was supposedly invented by Japanese bakers who immigrated to the United States).

And here's the kicker: In the early 1990s, Wonton Food, the largest fortune cookie manufacturer in the United States, attempted to introduce fortune cookies to China, but gave up because the cookies were considered "too American" by the Chinese.

You Can't Tell the Difference Between Cheap and Expensive Wine

Ah, the sweet nose of lies that is wine tasting. If you ever thought that pretentious wine tasting experts are full of it, you'd be right.

Psychologist Richard Wiseman of the Hertfordshire University conducted a blind test in which he asked 578 regular people to tell the difference between a variety of wine, ranging from cheap £3 wines to expensive £30 bottles:

The study found that people correctly distinguished between cheap and expensive white wines only 53 percent of the time, and only 47 percent of the time for red wines. The overall result suggests a 50:50 chance of identifying a wine as expensive or cheap based on taste alone - the same odds as flipping a coin.

So, in other words. They guessed.

Ah, but that's regular people, oenophiles said. What about experts? Well, the results aren't much better: In 2001, Frédéric Brochet at the University of Bordeaux tested 54 wine experts to rate two glasses of red and two glasses of white wine. The experts couldn't even tell that the red wine was actually the same as the white wine, but colored by red dye.

If that's not bad enough, wait till you hear what Brochet did next. He took a middling bottle of wine and served it in two different bottles. One bottle had a fancy grand cru label and the other one had an ordinary table wine label. The experts gave the same two wines opposite descriptions: they praised the "grand cru" wine and dismissed the ordinary one as less favorable.

Do you know of any more food lies? Tell us in the comments!

Continue to read 5 more food lies over at Neatorama.