Louise strolls into Jonathan's apartment, awkward and exhausted. She's still wearing her white lab coat from work. In fact, she almost never takes it off. It's her good luck charm, her safety blanket that gets her through days of sexually stimulating rats for research and nights hearing Jonathan rant about his failure of a dissertation on Pliny the Elder.

"Why don't you ever lock the door?" she asks.

"So it's easier to leave..." he replies.

"Leave-leave?"

"No, leave the apartment."

"When do you leave the apartment?"

"I just like to know that I could."

The problem is that Jonathan could leave-leave, but, of course, he won't. Louise won't either because love can become a snare that entraps even the most intelligent and ambitious and entreats them to develop webs of toxic codependence that are as unhealthy as they are habitual.

Perhaps this is the point that Obie Award winner Melissa James Gibson is chasing in her new play, Placebo, now at Playwrights Horizons. Or maybe she's hungry to dig into how sex affects couples -- the good, the bad and the ugly (in this case, mostly the ugly, or the nonexistent). She could be looking at how emotional intimacy has gone out of fashion among hardworking, career focused (read: self-interested) millennials like me. What I find in her production is an ode to all three of these themes and more, because really it's an analysis of the obstacles pitted against relationships in the 21st century and how human nature and our desire for connection don't fit in with the social construct of our era.

You have to experience Placebo's nuance to grasp all of it. There's too much substance, too much grit. Gibson never wastes words; even the most menial dialogue has an underlying thrust, a hint at dreams and disaster.

Every line of the script hides a new slant -- something to keep you up at night, restless in thought.

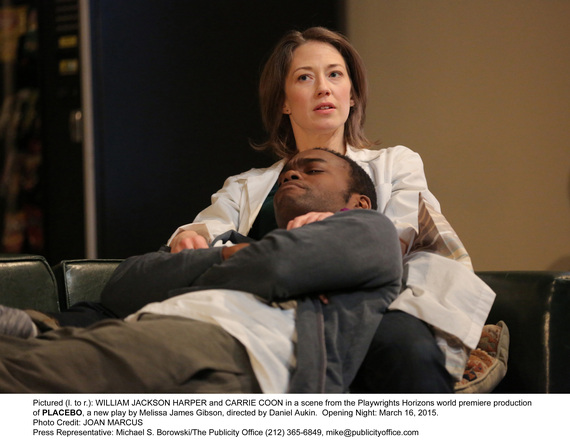

The action gets its humanity from four adroit actors, all of whom deliver moving, believable performances. Carrie Coon of Gone Girl and Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? fame is the protagonist, Louise. William Jackson Harper, Alex Hurt, and Florencia Lozano compose her supporting cast. Coon's bluntness is endearing, Harper's emotional viability convincing. Hurt proves captivatingly simple, and the upper-class privilege of Lozano's character makes her no less likable.

Placebo's plot is mundane, and its key events could happen to any of us. Louise works at a hospital developing a female version of Viagra. Her boyfriend, Jonathan, never ventures far from his apartment, where he buries his nose in books about the Roman philosopher, Pliny. Louise's mother is sick, and as Louise frantically fights to grasp her mom's mortality, Jonathan is too consumed by his studies to notice. So she turns to her coworker, Tom, for a good-humored listening ear. Sparks fly. Tensions erupt. Still, in the end, not much has changed.

But be warned: this is not your typical love triangle. We like our entertainment like our Kraft singles: fake. But it seems that Gibson doesn't care what we like; she's going to hand us the truth, unabashedly, with no euphemisms or concluding catharsis.

Instead of telling us what to believe, she'll show us why 40-50 percent of married couples eventually divorce in the United States and why one-night stands are the new normal. She'll make us wonder if a fairytale romance is possible when we're too individualistic to see past ourselves and our aspirations. She'll even have us question our own self-obsession and whether our drive to become someone is pushing away everyone else.

And finally, as the ensemble takes a bow, we'll ask ourselves if the people in our lives should be pushed away for our own good, or if they're worth the constant game of catch. Should we drop the ball or keep throwing, hoping that soon the motions will feel more natural?

But the problem here is the "should." Gibson makes it clear that what we should do isn't always what we choose to do. Sometimes, the heart gets in the way.