I'm currently sitting in a favela in the middle of Rio de Janiero. And let me tell you, there's nothing that can make you more aware of the specificity of your worldview than this. The streets are abuzz with activity, and not the kind you can find on an L.A. street corner: vendors selling shockingly small rations of peanuts, locksmiths (inexplicably) on every street corner. The un-graspable Portuguese that makes me lament the narrow language capabilities of American culture, despite my attempts at passable Spanish -- which I embarrassingly and quickly learn is far from useful here. The smell of raw meat, rotting fish, and -- sometimes -- fecal matter. And here I am, a suburban white girl, taking it all in. "Experiencing the culture."

This isn't my first trip abroad. In fact, it's my twentieth. I've got the bug, and I'd much rather sit in a tent in the middle of a rainstorm in Peru, foodless after miscalculated rations (actually) than in a nightclub in New York. Or climbing rock walls in Essaouira, butchering the pronunciation of aasif! when caught. It's thrilling, this thing we call travel, but it's also depressing, in a sense. Depressing because, despite how much we might want to, it is impossible to grasp the complexities and perspectives of a different way of life. Impossible to grasp much of the world. It sparks wars. Carves invisible boundaries into the Earth like a pocketknife. My manager constantly implores me to stop "writing like a suburban white girl." And he's right. It's concerning. Because the topics I choose to write full-on screenplays about happen to be the furthest things from my own experiences. Drug cartels in Mexico. The plight of Jewish children in Nazi Germany. How do you put a pen to paper, and write -- with any practical knowledge -- of these things that are so far afield of your own experiences?

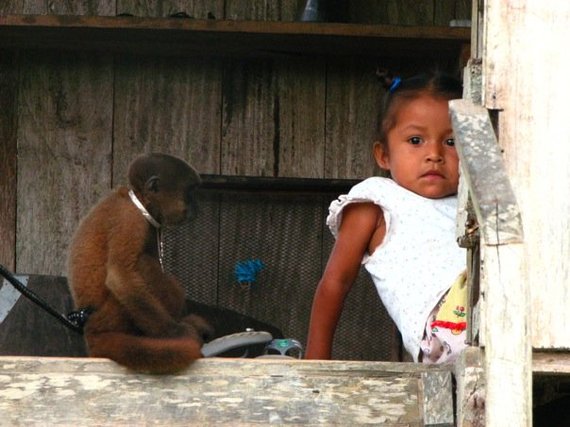

From childhood, we're told that we can put ourselves in the "shoes of a stranger," and imagine how life must be for a woman in a village in Mali, or how the world works for a street vendor in Tokyo. But in reality? It's impossible to insert ourselves fully into these other worlds. A main tenet of writing, expounded over and over again, is that human experiences are universal. To get to the meat of a story, you insert pieces of yourself into the fabric of your work. And paint the world around it. The result should be that I can write a story about sibling love in Indonesia just as easily as I can describe my childhood growing up with two younger brothers. But can I recreate the world in a meaningful way, keeping in mind this insurmountable Everest that we call a culture gap? Can I recreate the sights and smells of a life in Rio after just a week in the city?

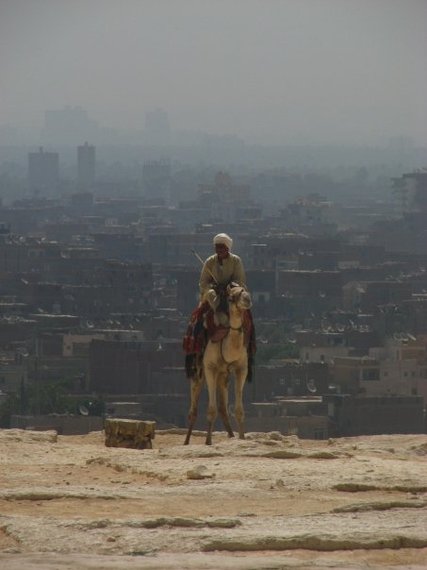

And when you leave your comfort zone, it is inevitable that you will be thrust into the riptide of a realization that--no matter how hard you try--you will only ever be able to experience the world from one single perspective. Travel is meant to immerse you in the world, but in reality it is only from the perspective of an outsider. Hemingway never truly knew what it was like to be Cuban. I slept next door to his apartment in Havana--the big pink building is a residence that most Cubans could only dream of.

Travel is eye-opening, in the sense that it opens your eyes to what you don't know, rather than what you do. And that's not always a bad thing: to echo a quote from Confucius that belongs on a poster in a high school classroom, "to know what you know and what you do not know, that is true knowledge." In America, we communicate without language barriers. We are confident in our own circles of friends. We become comfortable. But shake that up? And you know nothing. You're simply an American in a country that speaks Portuguese, and you'd better figure out the word for rice quickly if you want dinner. English is supreme, we say, and shame on you for not knowing it. In her fascinating book Lost In Translation, an Illustrated Compendium of Untranslatable Words from Around the World , #1 and sold out on Amazon, Ella Sanders illustrates just how large our barriers are. The word mangata (the road-like reflection of the moon in the water) doesn't exist in English: it takes us ten words to express this vague idea, and even then we might go with the quicker term: reflection. Yet--while purportedly similar--these expressions paint an entirely different picture in the mind. Constrained by the availability of words, we invariably have a different experience of this very same image. Our minds literally work in different ways, from culture to culture, and that is unavoidable.

So what to do? Embrace that which we don't know and fall to the curse of it, or engage in a Herculean effort to bridge it? The answer is in a bit of both: real-world experiences peppered with a bit of imagination is the recipe for coming as close as we can to others in this fragmented world. We can write a story about sibling love in Indonesia, but it will invariably be from the culturally uneducated perspective of the person we are. Our experience is simply one point of view in a world of seven billion, and we will never walk in another man's shoes. A deep-seeded curiosity of these other cultures, these other people, is the most we can hope to pursue.