"The American dream," that protean and paradoxical phrase, is held to first have been used as a definite concept by James Truslow Adams in The Epic of America (1931). Though the term "American dream" had appeared in print before this, critics have fallen neatly into line in crediting Adams with the phrase and its definition, which Adams supplied as "that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement. It is a difficult dream for the European upper classes to interpret adequately, and too many of us ourselves have grown weary and mistrustful of it. It is not a dream of motor cars and high wages merely, but a dream of social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable, and be recognized by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position." The American dream, even as Truslow writes it, is not an ideal dream, but a waking humdrum everyday one -- or worse. We've grown weary and mistrustful of being told that, if we can make it here, we'll make it anywhere -- and that anyone can make it, if they're "good enough," no matter who they are or where they're from. Failure is the fear at its heart from the start.

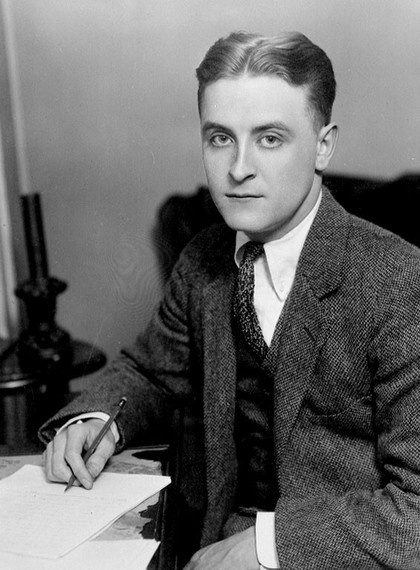

The American author most associated with the idea of "the American dream" is F. Scott Fitzgerald. His 1925 novel The Great Gatsby revolves around such a dream and its failures, with those motor cars and high wages proving crucial to the plot, and the young man born poor losing his dream and his life, while the rich folks "retrea[t] back into their money[.]" However, it was Adams who coined the term in its ironic fullness, not Fitzgerald.

Or did he?

In 1930, Fitzgerald was working on a story about a girl called Fifi. He'd worked on such a story before, when he was a Princeton undergraduate in the fall of 1914 -- a musical comedy called "Fie! Fie! Fi-Fi!" In the comedy, written for the Princeton Triangle Club's annual show, a manicurist, Fi-Fi (real name: Sady) is hiding out on the Riviera among the idle rich. There is a wild subplot that soon overwhelms the plot, featuring a rebellion in Monaco led by the bandit hero Count del Monti, who turns out to be the principality's rightful Prime Minister. Sixteen years later, Fitzgerald gave the name Fifi to a heroine once more -- this time, to a wealthy young Jewish-American girl, Fifi Schwartz, traveling in Europe with her mother and brother. Fifi is the title character of "The Hotel Child," partying at the Hotel des Trois Mondes on the night of her eighteenth birthday as the story begins.

With her jet-black hair and lovely body, Fifi is attractive to "a whole platoon of young men of all possible nationalities and crosses[.]" A "cynic had been heard to remark that she always looked as if she had nothing on underneath her dresses; but he was probably wrong, for Fifi had been as thoroughly equipped for beauty by man as by God. Such dresses--cerise for Chanel, mauve for Molyneux, pink for Patou; dozens of them, tight at the hips, swaying, furling, folding just an eighth of an inch off the dancing floor." In a "dazzling black" dress, celebrating her birthday, she amazes a young Hungarian, "Count Stanislas Borowki, with his handsome, shining brown eyes of a stuffed deer, and his black hair already dashed with distinguished streaks like the keyboard of a piano." A group of snobby blond Americans disapprove of Fifi -- "They considered that Fifi was as much of a gratuitous outrage as a new stripe in the flag" -- but Borowki is smitten, perhaps as much by the wealth Fifi embodies as by her self. At the end of a game of pool, he slips away with her to "a dark corner near the phonograph" and delivers the following line:

"'My American dream girl,' he said. 'We must have you painted in Budapest the way you are tonight. You will hang with the portraits of my ancestors in my castle in Transylvania.'"

Fitzgerald took a blue ballpoint pen, sometime in late 1930 or the earliest days of 1931, and changed a typescript "You are a dream tonight" to "My American dream girl." The dream was there to begin with -- but he chose to make it specifically American, and used the figure of Fifi to do it. Fifi, not a successful man or the cross blonde girl, is the "American dream." She defines the social order not only at home, but abroad -- though, in a departure from Adams's paragraph outlining the idea, Borowki, an alleged member of "the European upper classes," interprets her most adequately indeed.

Fifi's reaction to being called "my American dream girl" shows that she knows not only the possibilities, but the falsehood, inherent the phrase -- Fitzgerald is putting it in the mouth of the count for just that reason. Fifi may be the count's image of the American dream, as her family's made money justifies her being on the walls with his aristocratic ancestors in Transylvania. But she doesn't trust this possibility, or him. She is a "normal American girl" at the core, familiar with Borowki's flattering phrases from the dialogue of "an average number of moving pictures." Practical and hard-headed, she is managing an alcoholic brother and a baffled mother as well as her many European suitors, and Fifi makes her judgments, in the end, based on the cold reality of an American hundred-dollar bill and what it can buy.

I won't spoil the story for you by telling you what happens. Please read it for yourself, if you haven't already. But as you do, bear this in mind: The Saturday Evening Post published "The Hotel Child" on January 31, 1931 -- and this only after weeks of negotiation with Fitzgerald had passed. The Post's editors worried that readers would find the "characters shady, to say the least" and wanted Fitzgerald to sanitize them, but he resisted. He would later complain that "the Post cut the best scene when [some English hotel guests] kept feeding hashish to the pekinese."

F. Scott Fitzgerald versus James Truslow Adams: what do you think? I'd say Fitzgerald got there first. His construction, around Fifi, of the idea of an "American dream" and the bright, and dark, things it encompasses predates Adams's celebrated use, later in the same year, of the now near-epic phrase.

All quotations from F. Scott Fitzgerald, "The Hotel Child," from The Short Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald: A New Collection, ed. Matthew J. Bruccoli (1995) and © The Fitzgerald Estate