Now that baseball season has ended in New York, I'm in a hot-stove season funk. It feels like the boys of summer must still be playing, on these 80-degree days in Manhattan. Thinking about my team, the New York Yankees, and the way this year felt like conclusions all around -- Mariano Rivera and Andy Pettitte retiring, Derek Jeter injured, Alex Rodriguez facing a year and a half's suspension -- it's inevitable to remember the very last game at Yankee Stadium, if you were there. Here's what I thought at the time, five years ago....

Derek Jeter and Andy Pettitte, summer 2008 (photo by me)

September 21, 2008. A gorgeous summery day in the Bronx. Sunshine, and scattered harmless clouds in the sky. The bat, its white-taped hilt towering above the rubble and fencing around its base. In the distance, beyond it, the ivory upsweep of Macombs Dam Bridge. A trio of flagpoles, with American, New York state, and National Park Service flags lying limp against them. The beige-khaki walls of the Stadium itself, parting for just a moment, as the train slowed to reveal that glorious cut between the right-field upper tier and scoreboard. Green grass, a honey-brown base path, and empty robin's egg seats showed in the cut. This was what it was like to come out of the ground on the approach to 161st Street and River Avenue/Yankee Stadium at one thirty in the afternoon, on the 4 train, that day. Yankee Stadium, the last game.

My father, who grew up in rural Virginia with Murderers' Row on the radio as his first Yankees memory, and my dear friend Tom Roche, a New Haven man but no Red Sox fan, who first came to the Stadium in 1953, both still refer to it as "the Yankee Stadium." The, an integral part of its name. Things still work that way in New York - no need to add Yankee, if you have the the. "I'm going to the Stadium today." No one thinks you mean - or, rather, meant - Shea.

I got to the Stadium early, because I wanted to walk through Monument Park once more before it's dug up and moved, because I wanted to walk around the warning track and past the dugouts and behind home plate and have That Dirt under my feet and on my shoes, and because I couldn't even think of being anywhere else when I could be there.

The gates opened at one, but we all had to wait, of course. People had begun lining up very early. Many folks I talked to were at the Stadium for the first time, and had come from California and Ohio and Scotland. Most of us, though, seemed to be season ticketholders who hadn't sold our seats for plenty on StubHub - proud members of Plan C, the Sunday Series, with seats in the tier boxes and tier reserved sections, one of the best entertainment values in the city that never sleeps. There was a lot to see while we looked for the best entrance and then waited on line, holding our tickets carefully, not bending them. Joba Chamberlain's proud father, in his wheelchair, an affable and smiling man, posed for photographs with pretty women wearing on their backs Number 62, no name, of course. The old calliope past Gate 6 played on merrily. Spike Lee, in his pennant-bedecked Yanks cap, filmed us at Gate 4. Everyone had cameras, cellphones. Everyone turned their technologies on Spike. I took a picture, and saved my battery for later. Finally, the old green turnstiles with their cloudy, unshiny chrome arms began to turn again, and we were in.

I did what I always do: walk to the nearest tunnel leading from below into the ballpark. It's always the same place - a little to the right of home plate, past the edge of the net. Then I walk past the Yankees on-deck circle and dugout along the first-base line to the foul pole, and back, all the way around to the visiting dugout. For some reason, and I can't think what it was, I never went all the way to the left-field foul pole: that wasn't MY foul pole. Perhaps it's because the home runs I think of when I think of home runs at the Stadium - ones I've seen, ones I've read about - all went fair past MY foul pole in right. The one exception was Aaron Boone's, which went into the hands of a thin dark-haired man in a shiny blue baseball jacket a section away from me, somewhere out left, in 2003. Today, there was a young man at my foul pole, taking its photo, juggling with his hands full. "Here, let me hold your beer," I offered. "Thanks. Want some?" he asked. I declined (Miller Lite), and he put down his camera to reveal in one hand a box of Marlboros. "One last smoke in the Stadium? Don't get thrown out," I advised, and he smiled. "No," he said, unwrapping the foil within to reveal white dust. "Some of my dad's ashes. I promised him." And while I held his beer, the young man leaned over the wall and reached out with his long arms to scatter the ashes by the edge of the grass, on the dirt, in fair territory. I hugged him when I gave him his beer. He hugged me back, and then was gone into the moving crowd.

Right field foul pole, the last game (photo by me)

Usually, when I finished my walk around the grandstand, I'd head back under for the ramps up past the loge and skyboxes - a level from which I am happy to say I never saw a single Yankees game - to the tier. I walked instead of taking the struggling, battered escalators because I liked the old cement, the white and blue paint, the gradual irregular elevation, the sense of accomplishment when you got to the top. This time, I walked all the way from pole to pole, and beyond, from the cut I'd gazed into from the 4 train to the end of the seats above Monument Park. It was such a beautiful day - a beautiful day to stand on line for an hour along one of the ramps until we got into the sacred little patch of grass and brick and bronze. The flowers in Monument Park were pristine, newly planted fall mums and nicely tended end-of-summer impatiens, and everything spick and span - but one of the weeping cherry trees is dying from the top. Fitting, I thought, as I went onto the field. A rope line that people obligingly obeyed kept us off that grass, and guards in wildly fluorescent yellow shirts dissuaded anyone, or at least anyone I saw, from scratching for souvenirs, or from lingering along the procession. Keep moving, they urged us. I reached up and petted the "385-ft." as I passed it, ran my fingers over the Modell's ad. You couldn't help rubbing your hand against the wall as you walked, and no one stopped you. And you wanted to get your uniform dirty, too - a man in a DiMaggio jersey did just that, in right field, placing his palms on the track for a moment and then, beaming, rubbing the front of his shirt to leave a big pale redbrown patch. He'd worn that jersey for the last time. Now, he said, he'd frame it for his office wall.

Mike Mussina ambled out onto the field and approached the fans in left field. Standing against the rope with a Yankees rep, he posed, smiling, for photographs with a little dark-haired, dark-eyed boy, a Moose lookalike. Joe Girardi was chatting with people in front of the Orioles dugout - nice that the visitors, on this last day, were a fine old AL East team. A-Rod was the last of the Yankees to come and mingle, from a distance, stalking his third-base territory and smiling that dazzling white smile for hundreds of cameras, fancy digitals and CVS disposables. As the last of the fans, lucky fans, who'd gotten there early enough to take that inside-the-park walk, were ushered back into the left-field stands, the Yankees began to drift out from their dugout.

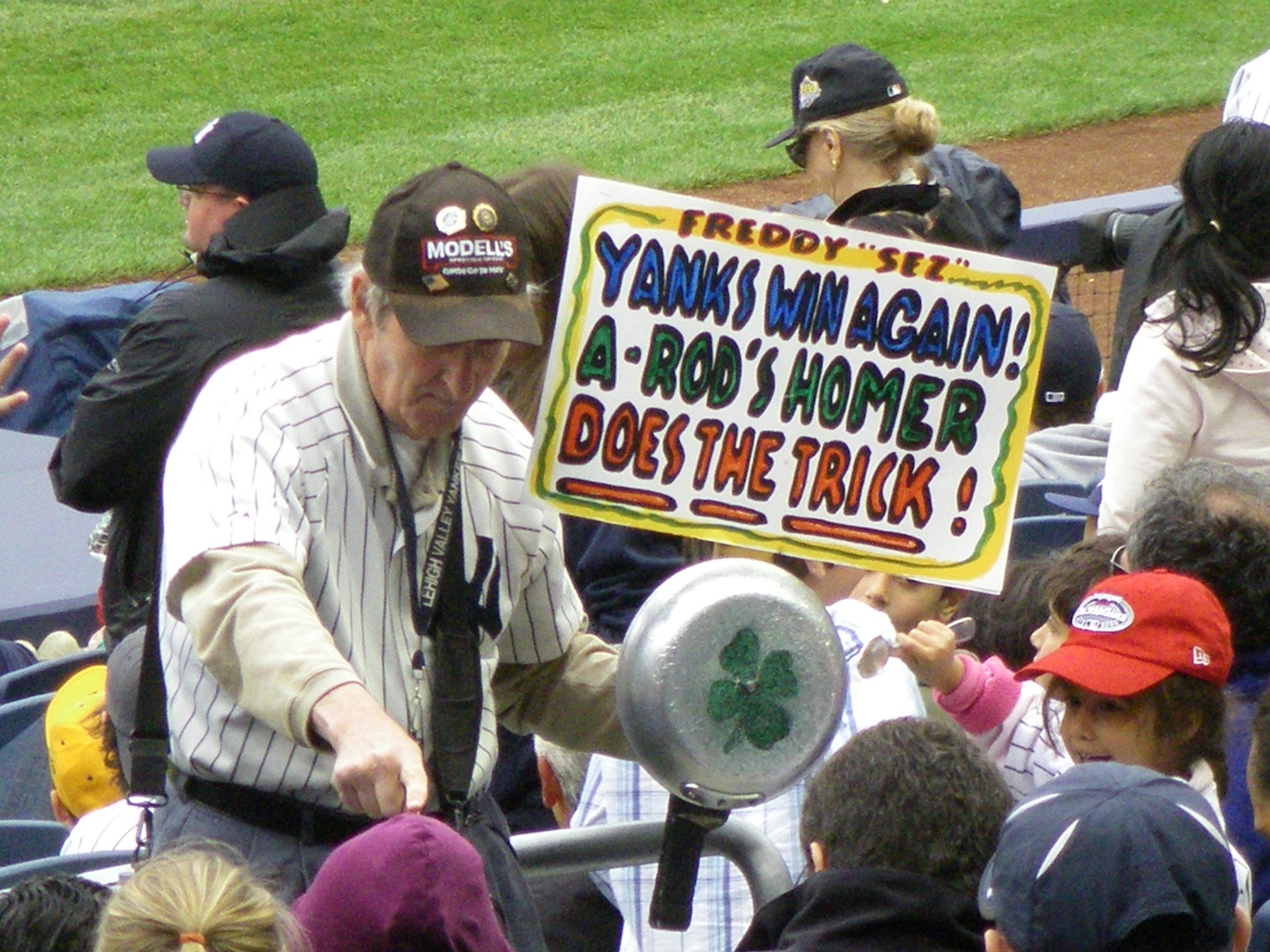

Certainly it was time for batting practice. I hadn't looked at the time, but when I looked up, I knew just what time it was, and smiled. The four o'clock pigeons are reliable timetellers at the Stadium. For years and years, during every single day game except for those washed out by late afternoon, the pigeons have taken wing in the vicinity of four o'clock. You can set your watch to it better than you can an English need for tea at the same hour: here they come, singly, in pairs, sometimes a whole flock of entitled pearl-grey grubby birds, sometimes a vivid white one looking more like a dove, all plump and well-fed, bobbing and weaving and sweeping up to settle in the lights. Leave, people, they say, so we can finish the Crackerjack and lumps of hot-dog bun and stray Bazzini peanuts. Here we were, twenty thousand or so of us, and the pigeons, ready for b.p., the pigeons biding their time (and today they'd have to wait), the people settled delightedly into, mostly, other people's seats in the Main box seats. Even on this last day, the chains stayed up to keep human earlybirds out of those empty Field boxes. No worries. We could see just fine. And Freddy was there behind the home dugout, with his frying pan and spoon. I took a turn and made some noise for good luck, thanks for the memories.

Freddy and his pan and spoon, the last game (photo by me)

Many of the Orioles had cameras. So did the Yankees. Jorge Posada, in uniform, snapped away. While the ESPN announcers set up on the field, hard by the Yankees dugout, greats began to emerge. Joe Morgan, a press pass against his white shirt. Paul O'Neill in a pinstriped shirt, brown not blue, reporting. Reggie Jackson, also in mufti, watching batting practice in a blue baseball cap that matched exactly the shade of the seats we sat in - or, rather, stood by; no one was sitting down. "Stand where A-Rod can rub against you. Change his hitting," shouted the guy next to me, when he saw Reggie behind the batting cage. We all laughed, ironically. The last game, and the start of hot stove season in the Bronx, most likely, for the Yankees were a loss away from being out of the playoffs. What a double whammy.

Graig Nettles, grinning, doubtless saying cheeky and memorable things, sat down in the chair behind the ESPN mics. I could still see him stretched out flat, chin about to hit the dirt where A-Rod now posed, glove on the ball, ball in pocket: Graig Nettles, my third baseman when I was a kid, Bucky next to him, continuing clockwise Willie on second, Bob Watson or Chris Chambliss on first, Thurman at home. For the first time, surprisingly, I felt a rush of emotion that ended up as sadness as I watched Nettles there, laughing. Above my head, a billow of bunting, red and white stripes, blue with white stars, wafted up and down comfortingly. It's a celebration, not a conclusion. You're Irish. Think of it not as a funeral but as a wake. Looking back at Nettles, I thought of the time a few years back when I watched a game down in New Jersey, with young Jim Nettles playing for the Somerset Patriots, and Sparky Lyle coaching him, and began to smile again.

The "closing ceremonies" were remarkable, better than I thought - or, honestly, feared - they'd be. And they were relatively brief. After all, there was a game to play. History and tradition are the two foremost words in the Yankees lexicon, and the ceremonies emphasized both. Things began in April 1923, and a parade of "the 1923 Yankees" - Wally Pipp got the loudest cheer - lined up in center field, a line of stand-ins in old-style uniforms (please, oh please, MLB, bring those back once more; the 1970s, with their tightfitting synthetics, were an evil and sartorially decisive time for baseball -- though mercifully not for the world at large). Then, a roll call began of the names of famous Yankees at every position. Late greats were succeeded by living players, who walked slowly or ran enthusiastically to their places on the field. Polite applause for Bill Dickey, there only in spirit, gave way to long, loud tribute as Yogi Berra, cap in hand, made his way to home plate; the cheers included tears as Thurman Munson's son Michael joined Yogi, wearing his father's number 15.

Women were in this final lineup at the Stadium: Elston Howard's daughter Cheryl; Catfish Hunter's widow, Helen, between Whitey Ford and Goose Gossage on the pitcher's mound; Cora Rizzuto walking out to short on the priceless escorting arm of Mariano Rivera; Bobby Murcer's widow Kay holding hands with their son and daughter as she jogged onto the field. Julia Ruth Stevens, the Babe's 92-year-old daughter, who admits that her many years in Conway, New Hampshire have made her a Red Sox fan (a Curse that's well and truly reversed, today), threw overhand a toss that rambled its way into Posada's mitt. First pitch over; ceremonies done; game under way.

Andy Pettitte was on the mound, where he's belonged since the summer of 1996, and boy, did I miss him while he was away in Houston. The lefthander from Ron Guidry country, a tall, dark, handsome man with a wicked slider, a slow-hanging curve, and the most expressive eyes in baseball (they're dark and unreadable as a shark's when he's on the mound, but you can always look at Pettitte on the bench and tell from those big brown eyes if the Yanks are winning or losing, and just how well or badly), deserved the honor of the last start, and he appreciated the fact. Pettitte was solemn and respectful as he arranged himself to throw; his pauses between pitches were longer than usual; and when the crowd stood to applaud him on two outs, two strikes, he looked near tears every time as he strode to the dugout at the end of the top of each inning.

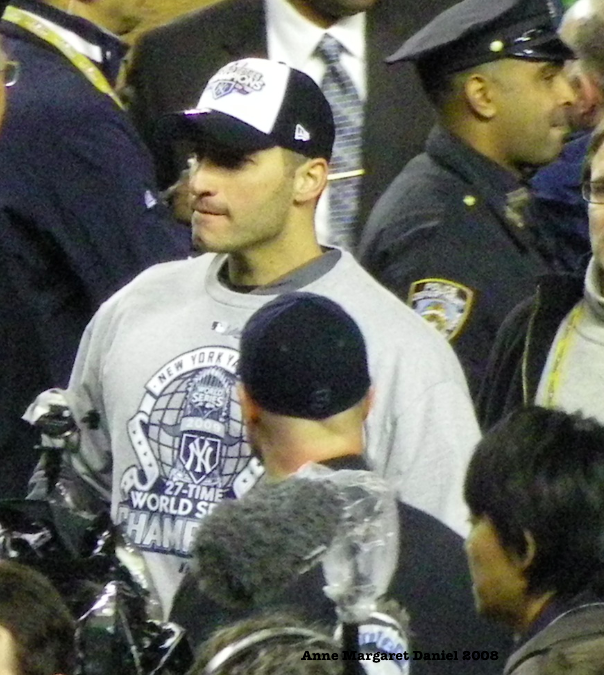

fast forward: Pettitte maintains composure, World Series championship night, 2009 (photo by me)

The Orioles scored first, in the second inning, and Pettitte made an error; the third also began badly, with speedy Brian Roberts racking up a second run for Baltimore. And then, in the bottom of the inning, Yankees leadoff hitter Johnny Damon, no longer a despised Bostonian, stepped up and smacked a home run into his favorite spot, deep right field - just like Maris's recordbreaker, just like so many Reggie shots. We erupted. Normally, I'm very fond of triples, and also of a soft single up the middle, but tonight everyone wanted fireworks, and we got them. Damon brought Hideki Matsui and Jose Molina home with him, and Molina obliged in the fourth with another homer of his own, to left this time. The Yankees kept adding runs here and there: RBIs from Jason Giambi and Robinson Cano, runs scored by Bobby Abreu and new crowd favorite Brett Gardner.

Pettitte threw 85 pitches, 63 of them strikes, in his five innings, and the game paused as the crowd roared for him when he sat down. Not just generously, but appropriately, Joe Girardi thanked his best relievers by putting in Jose Veras, the popular rookie Phil Coke, Joba Chamberlain, and last - and the farthest thing from least - future Hall of Famer Mariano Rivera. "Enter Sandman" played, and I started to cry. Weeping to Metallica? Just for you, Mo. Just for you. When Suzyn Waldman had interviewed Rivera the day before during the pregame show on 880 AM, she had asked him how he felt knowing he would throw the last pitch of the last game ever at the Stadium. Slowly, politely, Rivera replied that he hoped the Yankees had a lead at that point in the game, so he would indeed be put in. Rivera was flawless. He faced three batters, threw eight strikes in eleven pitches, and 7-3 the Yankees win, thuuuuuuuuuuh Yankees win. Frank Sinatra began to sing.

Rivera saves (photo by me)

We had been standing, already, and now we swayed along to "New York, New York." The teary harmonies in our section gave way almost immediately to laughter, though, as horses trotted onto the field. Mounted policemen in baby-blue helmets, about a hundred of them. Riot cops with thick Plexiglass shields and long black sticks. "What do they think we are, animals? Uh. Wait...." chuckled Jerry, the wiseacre at the end of the row. "Think anyone's gonna do a Wade Boggs?" the guy next to me wondered. I shook my head no; this wasn't an exuberant moment, like the World Series win when Boggs climbed on that horse. Only a couple of enthusiastic and misguided souls rushed onto the field - one only made it onto the warning track - and the cops were then delighted to have something to do. In right field, a good-natured and hungry beast third in the line of the mounted policemen bowed his head, sniffed, and then took a healthy chomp of turf. His rider pulled the reins up and rapped him disapprovingly on the shoulder. The horse rolled his eyes, kept chewing. When he was done, he assessed his chances, weighed them against the slightness of a tap on the shoulder, and bobbed his big head down for some more of Paul O'Neill's territory.

I had taken the 4 train to the ballpark because I'd wanted to see that approach to the Stadium in the sunlight. Now, I would take my train - the D train - home. What a long walk it was, along River Avenue under the train tracks, past the big cement planters full of brave battered roses, Stan's Sports Bar, the bleacher entrance, and the guys handing out leaflets for strip clubs. What a long, quiet trip home the twenty minutes to West 4th Street were. Anticlimactic? Not really. It was, simply, the end. This wouldn't ever be again.

Everything around the Stadium is already changed, and changed utterly, too. The old parking lot, the closest outdoor public one to the Stadium - the one you could flee into by heading down the ramp and turning left, underneath the Deegan Expressway, just after making it across Macombs Dam Bridge - is gone. A train station will soon be there. The plexiglass tunnel from the parking lots to the bat, the hottest place I've ever been on an August afternoon, and the best place, acoustically, for hearing the guy with the flute play "Meet the Flintstones" and the Addams Family theme song, is going too. On September 21st it was already planked in plywood at both ends. The Bronx Terminal Market warehouses that you drove past on the way down and over to the West Side Highway are gone, either high new flats of half-done parking garages, or rubbly dirt behind beaten-looking chain-link fences. Painted on the Deegan's thick supporting legs are the signs, the shadows, of the past: the rising numbers for the warehouse entrances, each in a different style, different paints; the ad for "Rosa Maria extra long grain enriched rice, Cuba Tropical Inc., Bronx Terminal Market, Bronx, NY 10451." The chorizo ad, with the vivid sombrero and serape backdrop. All going, going.

And of course the new ballpark is already rising there, too, where Macombs Dam Park used to be. We watched it grow, the cranes towering like an insult and injury together over the left field of the Stadium since the 2006 season. Over Labor Day weekend, I got there early for my Sunday game and found a place to slip into the big brownish colossus, and poke around for awhile. "Yankee Stadium," say the gold letters cut into its face. It's as big and cavernous as a European train station; it smells of wet cement, and feels like a brand-new multistory mall somewhere in north Florida. Camden Yards, replacing old Memorial, got the smells right - surely the harbor air, and Boog's Barbecue, helped. Maybe next spring the Harlem River, fragrant on a slow warm day, and the meaty mingling smells of Nathan's footlongs and Glatt's kosher dogs, sloshed lager, and fans' exhalations will remain magically in the air. But the four o'clock pigeons: will they take the shiny, pristine cavern for home, or are they gone forever, to Bronx rooftops, into the few remaining trees?

The space where Yankee Stadium was is meant to be turned into a park, to replace the playgrounds and park and playing fields long at the foot of Macombs Dam, wiped out by the new construction. They say the Yankee Stadium field will remain, base paths and infield and outfield and all, with trees rimming the ghostly tracks of the first and third base lines, outfield walls, backstop. That's nice: the idea of people playing ball on that field, having picnics where Mantle manned his position, of me being able to stand where Jeter stood near second and groomed with his cleats, regularly, his patch of dirt, is a happy one.

Tonight, in Fenway Park, the Angels try to stay alive in the postseason as I write this. I'm enjoying a tied game, and the field with its grass more Kelly-green than that of the Stadium, and Fenway's low muddier-green walls with everyone behind them wearing red. In the Bronx tonight, in the cold October air, the third-oldest ballpark in America still stands, pieces picked out of its wall by fans with (despite security's best efforts on that last night) screwdrivers and chisels and bare hands, roughened green turf starting to give in to autumn in New York, the Centerplate food service areas padlocked shut, the windows in the broadcast booths closed. Field of dreams, America? Here it is. The Stadium is ready to go again, come next April, if it could claim the chance. What the grand old ballpark doesn't know is that, to borrow words from three great American men of letters, it ain't over 'til it's over, but it's all over now - that there are no dreams now but only unresurrectable memories, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic roll on under the night.

Yankee Stadium entrances, early October 2008 (photo by me)

Author's note: I wrote this piece on October 5, 2008. The Red Sox won the game that night, and the ALDS, but would lose in the ALCS to Tampa Bay. However, in November 2009 I was at new Yankee Stadium when Andy Pettitte and Mariano Rivera combined for a win and save, once more, to give the Yankees their 27th World Series championship. The pigeons were there too, circling hopefully and patiently, when I arrived for batting practice that night.

A pigeon surveys its dominion, first game at new Yankee Stadium, April 2009 (photo by me)