Some people can't just let things drop. They just can't let them go. In some cases passion and commitment to a higher cause keeps them hanging on. Such is the case with National Geographic photographer Gerd Ludwig.

On April 26, 1986 at 1:23 am Chernobyl's Nuclear Power Plant reactor #4 blew up after a botched safety test triggered an explosion and caused a fire that burned for 10 days. The radioactive fallout spread over thousands of square miles and sent more than a quarter of a million people from their homes and now 28 years later it still darkens, damages and debilitates both the people and the land.

For the past 20 years, Gerd Ludwig, winner of the 2006 Lucie award for the International Photographer of the Year, has been telling the story of Chernobyl through his photographs. Cataloging the devastation's changing shapes and faces over time so that we will remember and not forget. So moved and motivated by the horror of Chernobyl that he has, over the last 20 years, made this his ongoing project and professional mission statement. Again, it takes passion, and commitment to summon the energy to keep giving one's all to anything for 20 years and that alone peaked my curiosity as to the origin of his passion for this subject.

"It was my father's bedtime stories" said Ludwig with a low laugh in his undiluted German accent. Making LA his primary residence for the past 25 years while he flies all over the world for National Geographic, hasn't minimized his accent the way time has turned his once blond hair more white than gray. He went on, professorial and sincere, to give me the story of how a born and bred German man could have so much affinity with the Russians and their plight to make it his heartfelt cause célèbre.

His father had been part of the Sixth German Army that invaded the Soviet Union in 1942. Barely making it out alive, he brought home images of snow covered fields and peasants in babushkas', memories of kindness as well as bloodshed. An ancient bent over Bubbe offering milk to a starving German soldier hiding in her basement. Soldiers huddled against the cold passing a cigarette from one frozen set of fingers to the next. Ludwig says his father processed what he'd witnessed into bedtime stories as a way of dealing, and possibly healing his war trauma. As a young man filled to bursting with the guilt of being German, straddled by the weight of his father's generation and the horrors they perpetrated, Ludwig's way of processing and possibly healing was to form an empathetic connection to the Russian people.

From his first trip, as a 30-year-old fledgling photographer on assignment for a European magazine, he says he felt an instant affinity for Russia and the soul of its people. With the stain of war on his soul he sought redemption. What he eventually found was another war, a different war of destruction and devastation that would indeed hold him captive. Later on, while working in Russia in 1993 shooting for National Geographic, in the midst of its chaotic transformation from a state controlled to a market controlled economy, Ludwig's shame based blindness towards Russia eased. He realized that government officials were motivated by greed and self interest to the detriment of their fellow citizens and to their environment, opening his eyes to the hypocrisy, deceit and cover ups on every bureaucratic and government level in his adopted land.

Photographing children in orphanages classified as victims of Chernobyl, opened Ludwig's heart and brought home to him the truth of the physical, mental and emotional devastation the nuclear explosion has caused. Children with missing limbs and cancerous tumors the size of grapefruit protruding from their foreheads told his camera their stories.

His photos of Pripyat, the town 3 kilometers away from the Chernobyl power plant, the once beautiful, thriving town built for the 50,000 power plant workers and their families, a town once throbbing with life and the laughter of little children, are of a grey ghost town devoid of any life at all. There, the stillness and complete lack of life scream at us in their silence.

Limbless children, abandoned school rooms crumpling and concrete grey, the wooded-over ghost town, all stares at us asking us to feel and remember. Through Ludwig's photos we do both.

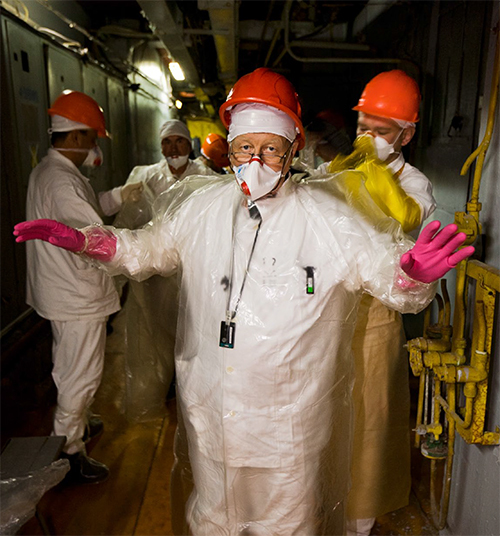

There are no words for the devastation caused by Chernobyl. Thank God we still have dedicated photojournalists to say it for us with their pictures. There are some people that hope we forget and encourage the easing of restrictions on power plants. They do not want us to think in terms of toxic land, contaminated machinery, poisonous DNA and cancer mutating cells. It takes the courage of a Gerd Ludwig who continually puts himself in harms way to keep the truth alive.

"Chernobyl is not over. The contamination will be here for hundreds of years. But it is old news" says the photographer. So how can he keep going back? Going back to those children, to those elder "returnees" who'd rather die on their own contaminated piece of land than relocate to a cold urban refuge, to the infants all grown up now and of child bearing age who worry about what deformities their own offspring might be born with.

"I go for dusha and dusha only" answers Ludwig, going on to explain "dusha" as the mysterious well of compassion, depth and empathy that is unique to the Russian soul. It is this dusha that Pushkin, Tolstoy, Chekov and Dostoyevsky, wrote of and tried to illuminate. And what Ludwig has glimpsed, and captured in Broken Empire, his love song in pictures to Russia published in 2001. The Russian soul, this dusha, that keeps dragging him back.

"As photographers we do this to give voice to otherwise voiceless victims," says Ludwig, and that the people in his photos know that the pictures of them won't change their lives but maybe they will protect someone in the future. This, noble as it sounds, is also what spurs Gerd Ludwig on.

Noted photographer Douglas Kirkland a contemporary of Ludwig's says that what impresses him with Gerd's work on Chernobyl is how "he has relentlessly pursued the story and fearlessly reported it in depth with great honesty and integrity."

The publication of this collection of photo's and text, entitled "The Long Shadow of Chernobyl", was first published in 2011 as an iPad App, and is now being published as a 20-year retrospective photo book, funded in part by a Kickstarter campaign to offset the high cost of printing. In the book, noted scientist Alexi Okeanov is quoted as saying that the health effects of the accident are "a fire that can't be put out in our lifetimes". Devoted photojournalist that he is, Gerd Ludwig, will spend the rest of his life chasing and shooting, its flames.

The Long Shadow of Chernobyl - A Photo Book by Gerd Ludwig

Support the book and pre-order today at http://gerdludwig.com/kickstarter

View more of Gerd's work at: http://www.gerdludwig.com

Learn about Gerd's Chernobyl coverage at: http://longshadowofchernobyl.com