Roughly two years ago, a female CEO in Silicon Valley made headlines for making less money than her male predecessor. This story became a media launch point for discussing the struggle with diversity in tech.

The story naturally made its way across the coast to Boston where a reputable, local newspaper requested my current company, HubSpot, to make a statement. The reporter asked to interview me. As I joined the call, I was prefaced with the following (not verbatim) ...

"I'm working on a story about a general lack of racial and gender diversity in Boston tech. I've talked to a bunch of folks and hearing how lonely and terrible it is, so wanted to weave in how you fit in with your experience as a Muslim woman."

I was instantly irked. The reporter was trying to feed me a specific angle, trying to make me admit, "why yes, it's terrible being a Muslim woman in tech! Here's why!"

But that's not the case. I responded with a very different narrative, which wasn't juicy enough to be published, so the article was scrapped. Today I'd like share what I said in my interview anyways, because it matters -- at least to me.

The Tech Path Less Traveled

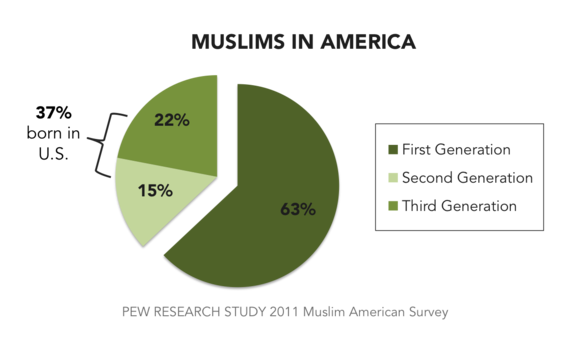

A Pew Research study found that there were 3.3 million Muslims in America in 2015, roughly 1 percent of the population. Meanwhile a 2011 study showed that 63 percent of Muslims in America were first-generation immigrants to this country.

Let's put some context behind those figures. Take my community in New Hampshire of roughly 150 South Asian Muslims as an example. Me, my siblings, and my friends are all the children of the aforementioned 63 percent of first-generation parents who immigrated to this country. Many of our parents moved here at a young age and faced their own struggles in trying to adapt to a new environment, new language and new social circles.

So when we (me, my sibs, my friends), were of high school age, we were told we could go into one of three fields: medicine, law or engineering. If I had to make up rough estimates of the routes we went, I'd approximate ...

- 60 percent went the route of medicine

- 15 percent law

- 10 percent engineering

- 10 percent other

Unfortunately, there haven't been any sufficient surveys to substantiate my estimations, perhaps further proving the overall ignorance of this nascent and growing community in the U.S.

In any case, I fell in "other." I chose to study journalism. This upset my dad. He didn't want me to encounter the same financial struggles he did moving across the Atlantic with his wife and newborn in hopes of a stable, comfortable life.

But worse than my father's fear was how I was belittled by the Muslims around me in the greater New England area. I was once told that as a journalist, I wasn't qualified to call myself a "professional." Later as I pivoted to marketing, someone told me that my career path was hardly considered a real job and required no intellect.

I was later rejected from the only (at the time) established organization that gathered Muslim business professionals to help them become leaders in their communities -- working in a communications role at a small software startup just wasn't prestigious enough when compared to folks at the major consulting firms.

With all this context in mind, the answer to why there aren't more Muslims in tech starts to become a little more clear.

A Turning Point

Nearly a decade later, this perception has started shifting. Working at a startup is suddenly seen as cool. Starting your own company is eliciting respect. And I bet if I applied to that Muslim business professionals group again, I'd probably get in (but I have more self-respect than that).

The driving factor behind this progress stems from the growing number of tech businesses that are emerging, signaling to the greater community that other job functions can lead to a profitable career path.

Look around Boston, and you can see example success stories in action. At one point at HubSpot, there were two Anum's -- yes, two young, Pakistani, Muslim women with the same name! My marketing twin, the lovely Annum Munir, is now a Product Marketing Manager at Twitter.

Even the Muslims who initially pursued medicine are widening the horizon of their career opportunities. Some medical students are spending an extra year to also complete their MBA degree. Others are focused on building their own MedTech startups in lieu of practicing medicine post-graduation.

For more examples, see any of the posts below.

- CNNMoney features four Muslims in tech

- Forbes 30 Under 30 2016 features Amani Al-Khatahtbeh, who started MuslimGirl, a Teen Vogue webshow on Muslim topics for non-Muslim teens

- American Muslim Consumer Consortium (AMCC) features 16 business led or started by American Muslims

The point here isn't to dismiss the lack of diversity at your own tech startup or company. Instead, it's to provide more context behind why there aren't swarms of Muslims at every tech company.

The best part? There's a major population of American Muslims committed to working hard and driving results in pursuit of a meaningful career that also makes their parents proud. If you're interested in finding these GSD employees, keep reading.

Where to Recruit

The shifting landscape of Muslims entering tech has led to the creation of more events, groups, and opportunities, three of which your company can get involved in. I've had personal experience with each of the following, which has helped me build a referral pipeline for HubSpot positions as well as internships in greater Boston tech.

1. Volunteer at a local MIST tournament.

MIST (Muslim InterScholastic Tournament) is an annual tournament for high school students. There are 14 cities MIST operates in across the U.S. and Canada, each with hundreds of Muslim high school students competing in a series of events.

In recent years, the organization added a Social Media Competition that includes everything from web development to blog writing. Other relevant competitions include:

- Short Film

- Graphic Design

- Extemporaneous Speaking

- Business Venture

Just this year, one of the students I met at MIST Boston years ago signed on to join HubSpot full-time after graduating college in May.

2. Attend a global Pakathon event.

Pakathon is a global organization in over 15 cities with annual hackathons designed to help Pakistani professionals launch their own business. In addition to attracting young professionals world-wide, Pakathon recently opened up university chapters to allow college students to start concepting and prototyping their startup ideas.

By attending one of their events, you can see a number of South Asian Muslims pitch their business ideas, giving you a live demonstration of how they think, present, and respond to critical questions on the spot from judges.

3. Sponsor offsite opportunities for current employees.

Early in my career at HubSpot, I was fortunate to have a mentor who sponsored a trip to Silicon Valley where I participated in a week-long hackathon. I networked with Muslims at Google and LinkedIn, received mentors who had already launched a number of business, and fleshed out a startup concept with an incredible group of fellow young Muslim professionals that we later pitched to Muslim VCs in the Bay Area.

This was a pilot program by the Muslim Public Affairs Council (MPAC). Even though the Silicon Valley Summit isn't currently offered, there are other valuable summits to take advantage of.

So there you have it. All the details from the interview that weren't newsworthy-enough to be published.