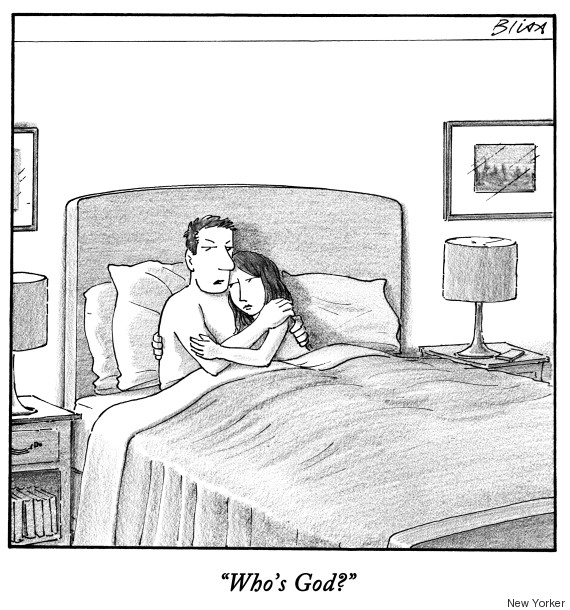

My observance of Yom Kippur this year was greatly enriched by a recent New Yorker cartoon by Harry Bliss that provided useful entrée to the highly serious matters that occupied Jews for the long day of fasting and prayer.

It takes a minute to get the "God" joke: part of its appeal--"Who's God?"--has never been an easy question for Jews to answer. Indeed, according to some Jewish thinkers, the question--as posed by theologians--is not even the right one to ask.

Yom Kippur invites Jews to step out of ordinary time and space, suspend normal operating assumptions, and enter a ritual realm that we do our best to make holy. The day simultaneously forces us to confront aspects of ourselves that we might prefer to avoid and brings us to the neighborhood where God can be sought and perhaps found. Both efforts require honesty, courage, and immediacy. The point of the exercise is relationship--and love.

For the great German-Jewish philosopher Franz Rosenzweig, the starting point was to realize that reality is comprised of three fundamental elements. There are human beings. There is the world outside of humanity. And there is God. We cannot fully explain any of the three. All--not least ourselves--remain mysterious. Rosenzweig firmly believed that in a way one cannot explain scientifically, we and the world are both products of intention. Human beings mean something.

The second lesson Rosenzweig offers to Jews and others at Yom Kippur comes from a book called Understanding the Sick and the Healthy that he wrote, uncannily, right before he contracted ALS and, a few years later, passed away. The search for truth can be deadly if it dominates life, he warned. There is an honored place for scientific investigation. It is good for the world that talented and highly trained men and women stand aside from life for a major portion of their lives, peer into microscopes and telescopes, and acquire knowledge of how things are and how they work.

There is value to philosophy, which turns analytic scrutiny on the way we think and speak and ponder the true and the good. The danger, Rosenzweig wrote, is that "any man can trip over himself and find himself following the trail of philosophy" to the exclusion of all others. "No man is so healthy as to be immune from an attack of this disease"--the disease being that we hang back from life until we have figured it out, stay away from love until we are sure, and keep a safe distance from God.

These three are intimately related to one another; at the very center of his great book, The Star of Redemption, Rosenzweig asks how God can order us to love, as God does in the two fundamental commandments of the Bible, "Love your neighbor as yourself" and "Love the Lord your God." Can love be commanded?

God is saying to humanity in the Bible, through the people of Israel, "I love you. Love me back. Love my other children, your sisters, and brothers." None of us can say much about our love for those we love the most. Can you explain your love for your partner or children? There's also not much we can state definitively about God or about our love for God. And yet we do love and thereby testify to the truth of love. We stake the meaning of our lives on its reality. This saves us.

Who is God, whose name Jews invoked many hundreds of times in the course of Yom Kippur? I can say three things for sure about God, all unscientific in the extreme, on the basis of the Yom Kippur liturgy.

One is that, like love, God lives in relationship, not in detachment. Yom Kippur assiduously avoids having us speculate about God. It wants to bring us into God's presence. Right before Jews confess our wrongdoing before God together and ask God's forgiveness, we proclaim God's multifaceted relationship to us:

We are your people, and you are our God.

We are your children, and you are our parent.

We are the ones You address, and You are the One to whom we speak.

The second thing I am pretty sure about, thanks to the liturgy, is that every one of the dozens of attributes and predicates we ascribe to God is required to try and capture the plenitude of our experience and reflection, our needs and our aspirations concerning God. The sum total of these adjectives, ancient and modern, are still not adequate for the task. We call God sovereign, teacher, redeemer, and friend--speaking not as philosophers or scientists but as witnesses offering testimony to personal encounter and heartfelt longing.

The third lesson is that the "Who's God?" questions should be contemplated in community. "We" is everywhere in the liturgy. "I" is rare. None of us stands alone. I am not the only one in any room that counts, not the center of things, but a part of a story that began long before us and will continue after we are gone.

On Yom Kippur, as we work hard to answer the questions that really matter, the issue to be addressed is not who God is, but who we are. That answer will be determined by how we live in the year ahead and how we love.