My mom and our family car during my high school days.

My mom and our family car during my high school days.

It's common for people who live through stressful and traumatic moments to forget them. I was no exception. What I do remember are the phone calls with my immigration lawyers, asking them on every call what the U.S. deportation process was like and how much time I might have to pack up my life. But try as I might, I couldn't remember. I would forget right after I'd hang up.

Fortunately for me, I was at least on a call with real lawyers, unlike the last ones our family used.

My parents and I arrived in the U.S. in 1992, when I was 14 years old. Although we were Korean, we had arrived by way of Hong Kong, having lived there for almost four years. After attending an American school and being fluent in English, I had little trouble adjusting to the California high school system.

My father received an H-1B work visa and then became a legal permanent resident, getting a green card. My mother and I received our green cards through my father when I was 17. To get our green cards expedited, we paid $45,000 for legal services, fees and documentation for the three of us to an immigration brokerage service. It was a herculean sum of money for poor immigrants like us, but the American immigration system was hopelessly complicated and confusing. This was my first experience with how expensive lawyers could be.

We paid the brokerage service on an installment plan, and our family of three moonlighted as janitors in addition to school and work to pay for it. I still recoil at even the memory of the stench of stale coffee and rancid soda cans that I collected from office trash cans to help make ends meet. High school, after-school activities, homework, dinner, janitorial work, go to bed at midnight. Repeat. Weekends were filled with helping my father with his painting business, cleaning out trash and dead cockroaches in apartment buildings so my father could paint the walls. It was hard, and it instilled in me the value to never be afraid to do the dirty work.

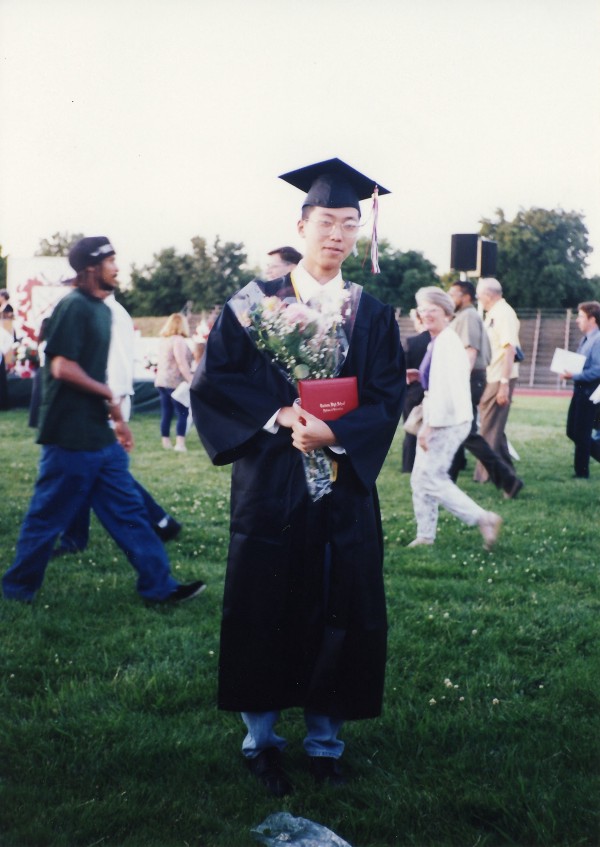

High school graduation in Rancho Cordova, California.

High school graduation in Rancho Cordova, California.

Little by little, we chipped off the debt that built our American dream.

Except there was a problem.

It was my senior year winter break from Northwestern University in 1999. It was pouring rain, and we were in my parents' car in the parking lot of a Target store when my father's cell phone rang. It was Daniel Lee, the immigration broker who helped my father with his green card application. Lee was calling to ask for help in paying his legal bills. It turns out he had been arrested, and the Department of Justice was prosecuting him.

We had a hard time understanding what his legal troubles had to do with us. Then Lee made a vague threat that if he was convicted, the Department of Justice would overturn all our green cards. We sat stunned in the car.

We would later learn that Lee and an Immigration and Naturalization Services official named Leland Sustaire cooked up a scheme where Sustaire would rubber-stamp green card approvals in exchange for cash. Instead of paying attorneys and following the process as he'd advertised, Lee had split our hard-earned money with a corrupt INS official. From our perspective, everything looked legit. We filed official paperwork, we went to the INS office for our interviews and fingerprints, and we received our hologrammed pink green cards in the mail after many months of waiting.

"The problem is not the fault of the people who work inside the machinery; the fault lies with us, the citizens, who demanded that machinery be built and left it unchecked as it grew more complex, more dehumanizing, and more self-serving."

Eventually, 275 people, including the three of us, would have our green cards confiscated. My father became a key witness on behalf of the Department of Justice and helped convict Lee. My father didn't ask for a deal, or any conditions for his help. He believed that by "doing the right thing" to help the Department of Justice, they would in turn recognize our status as victims of fraud. In fact, the special agent working on the case wrote a letter to our immigration judge explaining that we had no idea Lee had bribed an INS official.

It was no help.

Even though we were in the U.S. legally and all three of us had been ruled eligible for our green cards, the INS began the process to deport us. The INS demanded we show proof that we were innocent. But Sustaire had burned our documents, leaving us with little to no evidence to help our case. We were presumed guilty until we could beat the agency that screwed up in the first place. Justice isn't blind; she has a twisted sense of humor.

We hired another set of lawyers and fought for our innocence. The legal arguments for deportation seemed comically cruel. According to the INS, we didn't have legal status to stay in the U.S. because my father's H-1B visa had expired. But the only reason the visa had expired was because the INS had issued a green card -- a green card they couldn't even prove was issued improperly, since Sustaire destroyed the documents. Then, as a final blow, the INS shifted the burden of proof to us instead to prove that it was done properly.

Imagine that you're driving on a road with a posted speed limit of 45. Then a cop pulls you over and gives you a ticket for doing 20 miles per hour over the speed limit of 25. You point to the sign and ask the officer why she's issuing you a citation. She says that a city employee changed the speed limit on the road without authorization. Your only recourse is to fight it in court and prove that you had nothing to do with the sign being changed.

They fucked up, but we were the ones who had to pay.

I use the term "fucked up" in a technical sense. As part of his plea deal, Sustaire never saw the inside of a prison, and ended up with a fine and probation.

One by one, the 275 victims of fraud were deported, or gave up the fight and left the country. Having left Korea at the age of 10, I could not imagine leaving the U.S. This was home.

Then 9/11 happened. Immigrations laws became tougher, and the INS split into several new agencies. Rules changed. People changed. Our future got dimmer.

"Our immigration system is an immoral mess that throws obstacle after barricade in front of the huddled masses yearning to breathe free."

We were one of the lucky few. After eight years of legal battles and even after being issued an order to be deported from the U.S., we won. And later, I became an American citizen. But the legal appeal after appeal had cost our family more than $50,000. There was yet another monthly installment plan, the last of which was paid this year.

Still, the financial costs paled in comparison to the emotional and psychological ones. We could not leave the country since any border crossing would mean that we'd be denied re-entry home. Whenever I travelled by air even within the U.S., I carried a letter from my attorney declaring my innocence. Even a traffic ticket was cause for concern, as it could damage our "character" as we appealed for our existence in court. But the most painful moment came when my grandmother passed away in Korea. My father couldn't visit her before she died, nor attend her funeral. None of us could. He couldn't explain to his brothers and sisters why he had forsaken the mother who raised six kids by herself in the war-torn 1950s South Korea.

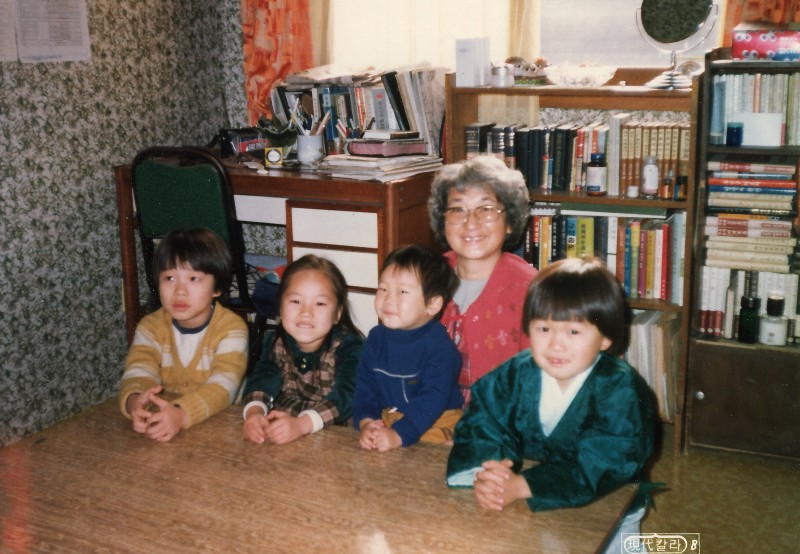

My grandmother with me on her lap. I saw her for the last time in 1989.

My grandmother with me on her lap. I saw her for the last time in 1989.

The American immigration system knows no mercy.

It is incomprehensible to its subjects -- the immigrants -- and puts them at the mercy of middlemen who prey on them. Its humanity has been extracted to pay for the sound bites of politicians who have never walked a mile in an immigrant's tattered sandals. Logic becomes twisted once it passes through the meat grinder of bureaucracy and is used to build careers, not help the people who need it.

It's difficult not to become jaded or bitter as you fight a faceless bureaucracy. The immigration judges, the appeals panels, the government lawyers, the federal agents -- all of them are trying to do their job. The problem is not the fault of the people who work inside the machinery; the fault lies with us, the citizens, who demanded that machinery be built and left it unchecked as it grew more complex, more dehumanizing, and more self-serving.

But even stronger than the bitterness and anger is my desire to find my purpose. I am a problem-solver, an optimist and an entrepreneur. And to be that person, I had to let go of the humiliation, frustration and anger.

Our immigration system is an immoral mess that throws obstacle after barricade in front of the huddled masses yearning to breathe free. It doesn't prevent terrorists from entering the U.S. It doesn't prevent criminals from entering our country. And it certainly doesn't excel at making America more competitive or innovative.

Our immigration system can be made simpler, fairer, safer, more humane, and more beneficial to the economy. Immigration powers American innovation across all industries, yet politicians hamper it with fear-mongering and blatant racism.

Meanwhile, we all pay the price. I know I earned my right to call myself an American.

--

Ben is the founder and former-CEO of the Cheezburger Network and co-founder of Circa currently filming drone videos around the world.

This post originally appeared on Medium.