There is no way to make up for decades of discrimination that crippled the proud history of black farm ownership in this country. But we can do our best to move forward.

In 1999 the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) settled the civil rights lawsuit Pigford v Glickman. They agreed to compensate thousands of black farmers who suffered racial discrimination at the hands of the USDA's farm loan program between 1981 and 1996. In the last three years, the federal government has started to provide relief to a second group of black farmers, as well as thousands of Native American, Hispanic, and women farmers who suffered discrimination of their own.

These initiatives have come under recent scrutiny and accusations of fraud. But many critics do not know the full story. The Pigford settlements only just begin to make up for the long and ugly history of discrimination against black farmers and other farmers of color in the United States.

Like so many great ideas in our nation's history, the USDA farm loan program was the product of compromise. In 1935, mired in the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt developed a plan to help struggling farmers pay off their debts and stave off bankruptcy. But the initiative first had to earn the blessing of White southern senators who dominated Congress.

These senators insisted that the federal funds should funnel through southern plantation owners and wealthy white farmers. The white farmers would then distribute the loans to their black tenants and sharecroppers.

In practice, they were often not inclined to pass the funds along.

This dynamic only grew more toxic in the 1960s. As civil rights protests rocked the nation, USDA staff intentionally withheld loans from black farmers who voted, helped register voters, or joined the NAACP. This discrimination continued in the years that followed, and it had a devastating effect on farmers of color. According to the Census of Agriculture, between 1920 and 1992 the number of African American farmers declined from 925,000 to only 18,000.

Despite this history of flagrant discrimination, President Ronald Reagan abolished the USDA Office of Civil Rights in 1981, leaving farmers with no options for legal recourse. The office remained shuttered until 1996, when President Clinton re-opened its doors.

That 16-year period of lax oversight was the basis of Pigford v Glickman. In the eighties and early nineties, thousands of farmers of color were denied access to loans; information on farm programs; technical assistance; and adequate loan servicing from the USDA. Some farmers were denied applications outright, while others were asked to fill out an application only to watch the local USDA supervisor throw it in the trash. At the time, these farmers had nowhere to turn.

In recent weeks the Pigford settlement program has been attacked with accusations of widespread fraud. These attacks are simply unfair and untrue. Since the first settlement in 1999, a careful process has been in place to weed out potential fraud. All farmers who claimed discrimination were obligated to sign a form under penalty of perjury attesting to the veracity of their claim. Out of 22,000 claims filed, only 60 of them were investigated for fraud by the FBI -- less than one percent of the total.

Moreover, many farmers of color suffered discrimination but were left out of both settlements. As Judge Paul L. Friedman wrote in his 1999 opinion, Pigford v. Glickman was a "significant first step" in addressing the USDA's broken promises and history of discrimination. But it should not be the last. One promising solution is the farm bill that will soon be debated in Congress, which will ensure funding for programs to further assist farmers of color.

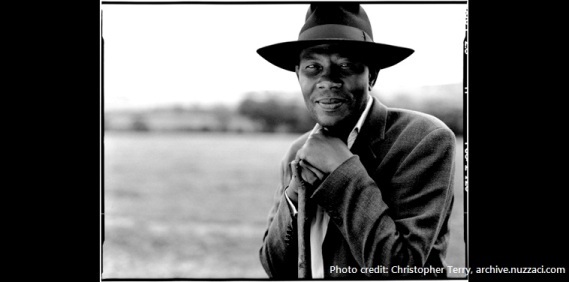

I spoke about this issue with Ralph Paige, Executive Director of the Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund, one of the oldest and most respected black farmer coalitions in the country. He told me, "When we overcome racial injustices like this, we benefit society as a whole."

This is certainly true. The Pigford settlement has helped the USDA begin to move past its ugly history. We encourage the Department to continue to welcome farmers of color as partners and clients, and to offer them the respect they deserve and the services they still so greatly need.

This column is reprinted from The Trice Edney News Wire