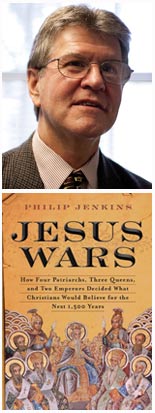

Christian scholar Philip Jenkins has written more than 20 books, which have been translated into a dozen languages.

His controversial new book, Jesus Wars: How Four Patriarchs, Three Queens, and Two Emperors Decided What Christians Would Believe for the Next 1,500 Years, was just released. In it, he writes in bloody detail about the violent story of the Church Councils of the fifth century. Perhaps the book's biggest shocker is that it was almost decided that Jesus was not human -- a theological wrinkle that would have changed the course of Christianity forever.

I caught up with Jenkins to discuss his new book, militant Muslims, and the current scandal surrounding the pope.

You write about the Church Councils of the fifth century and how it was almost decided that the church might formally abandon the notion of Jesus being both human and divine and describe him solely as divine. How would that change have impacted modern-day Christianity?

You write about the Church Councils of the fifth century and how it was almost decided that the church might formally abandon the notion of Jesus being both human and divine and describe him solely as divine. How would that change have impacted modern-day Christianity?

Part of the impact is ethical. Assume that the church proclaimed a Christ who was, in essence, divine. In that case, how could we talk about following or imitating Christ, if he was not once a man who had shared our weakness and our temptations? If he was just a God visiting earth as a divine tourist, how would we dare ask "What would Jesus do?" We could worship Christ but not try to change the world at his command. And how could we talk of atonement -- the core doctrine of Christianity -- if Christ had not fully shared our natures? Basic to Christian thought is the belief that we died with Christ, and rise with him. But for that to work, we have to share his nature.

The doctrine of Christ's humanity is also critical for the arts. Now, at various points in their history, both Judaism and Islam have had great traditions of depicting human figures, but often, they have condemned such art as a form of idolatry: you can't depict God. Christians maintained a sacramental vision by which God had reclaimed matter, so you could and should have visual images of Christ, which meant those incredible figures of the suffering Christ, Christ on the cross, and so on. The doctrine of Christ's humanity is responsible for a great deal of Western art.

In your book, you draw a line comparing militant Christians and Muslim extremists. In what ways are they similar and how are they different?

The level of Christian violence in that early era is amazing. You have bishops and patriarchs commanding armed mobs of holy men and monks, who they turn out against rivals, very much like Muslim mullahs or ayatollahs in Iraq or Lebanon today. They issue anathemas that throw rivals out of the community of faith, very much like modern fatwas. Mobs murder rivals over theological issues, they behead them and carry their heads around the street. Monks serve as private clerical militias, holy head-breakers. Religious controversy in Christian Egypt or Syria back then sounds a lot like the modern Middle East. I'm not suggesting that ethnic or geographical determinism made people act this way over the centuries. Rather, these are cultures with a strong belief in honor, with all the implications of revenge and vendetta, and violence is the only proper way to react against anything that seems like an insult to God, an attempt to take away his proper status and titles. As to how they're different? I don't see much difference in principle.

One of your earlier books is Pedophiles and Priests: Anatomy of a Contemporary Crisis. What are your thoughts on the current crisis surrounding the pope?

I wrote that book back in 1996, and it's been disturbing to see how the crisis has moved on since then. Much of the media response is based on questionable assumptions. However hard this may be to believe, there is in fact no evidence that Catholic (or celibate) clergy abuse children at a rate any different from other professions dealing with children: we really have no comparable figures to go on. (The limited studies we do have of public school teachers suggest a startlingly high volume of abuse.) Perhaps priests are better than Protestant pastors or public school teachers in this regard, perhaps worse: we just can't say. What makes the Catholic dioceses different is that they are pack rats who keep records from many years ago, which makes them easy to sue. The vast majority of cases that we've heard about in the past few years are also from the distant past, virtually all from before 1990. Attitudes to child abuse have changed amazingly through the years -- you'd be startled to hear what mainstream psychiatrists and therapists were saying about both offenders and victims back in the 1960s and 1970s. Catholic authorities are being blamed for decisions taken back in 1975, say, which were perfectly defensible according to the standards of the time, but which look so vicious and reprehensible through the lens of 20-20 hindsight.

Philip Jenkins' new book, Jesus Wars, is available on bookshelves now.

---

Benyamin Cohen, the author of "My Jesus Year: A Rabbi's Son Wanders the Bible Belt in Search of His Own Faith", is the content director for the Mother Nature Network.