An appalling abdication of responsibility by world leaders

I have just returned from COP18 in Doha, Qatar, and yet another UN climate conference. A total of over 17, 000 people descended on the small Gulf state last week: representatives from nearly 200 countries, an army of bureaucrats, members of the business community, academics, and civil society.

Theoretically, the aims of the UN Conferences of Parties or COP are: to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions, limit the global temperature rise to below 2ºC, and avert catastrophic climate change.

What was accomplished at COP18? Perilously close to nothing. The talks limped 'listlessly' to the finish line.

'Never let it be said that climate-change negotiators lack a sense of the absurd...' begins an article published in the Economist magazine on December 1st 2012 . The article calls the UN climate conferences 'theatre of the absurd,' a 'jamboree.' 'Climate policy is going nowhere fast,' it states.

It's hard to argue with the Economist's assessment.

Commentators were scathing about the choice of Qatar to host the COP: an oil rich country which has the highest GDP per capita , the highest carbon emissions per capita , and the highest water usage per capita of any nation on the planet.

The COPS don't set a good example for sustainability. Thousands of people fly many miles to attend. The conference centres are sealed environments, frequently heavily air conditioned and in the past have produced huge amounts of paper and plastic waste.

There were some efforts to make COP18 more sustainable; PAPERSMART, a system of paperless documents was implemented for the first time, a vast improvement on past conferences. At the end of COP15 the Bella Centre in Copenhagen looked like the Wall Street trading floor after Black Monday. Drifts of discarded programmes, notes, papers, newspapers and rubbish littered the floor.

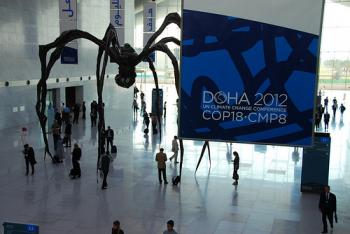

At first the air inside the Qatar National Conference Centre (QNCC) was very cold, the organisers overcompensating for the Qatari heat with high air conditioning throughout the vast building. After people complained, the levels were adjusted to a slightly more bearable temperature. Shops sold solar powered mobile phone chargers in the hallways.

As one crossed the atrium in the QNCC, one walked under a giant metal spider. 'Maman,' the 9 metre high, 8-legged bronze and steel sculpture by Louise Bourgeois, towers above the hall. A sac hangs from the belly of the sculpture containing seventeen marble eggs. Bourgeois's explanation, on a plaque on a nearby wall, reads: 'The spider is an ode to my mother. She was my best friend... Like spiders, my mother was very clever... spiders are helpful and protective, just like my mother.'

Maman should have been a good omen for the conference. The sculpture should have been a symbol of the sacred trust we owe to our children. It should have reminded world leaders of their duties to humanity and mother earth.

But Louise Bourgeois' message was ignored by world leaders at COP18. It was not the only important message they ignored.

At times the conference descended into farce. On the afternoon of December 5th British peer and climate change sceptic Lord Monckton entered the 'Stocktaking Plenary' hosted by COP18 President Al Attiyah, sat in Myanmar's empty seat and addressed the plenary. One observer told Responding to Climate Change: "The President didn't realise - nobody did for while - that it wasn't Myanmar so he went on about climate change not happening or something along those lines. Then he walked out himself."

At other times tragedy came to the fore. Naderev Saño, chief negotiator for the Philippines, made an impassioned plea in his statement to the COP on the 6th of December . Half way through, he broke down in tears as he described the devastation that typhoon Bopha has wreaked in his country.

'As we sit here in these negotiations,' he said, 'even as we vacillate and procrastinate here, the death toll is rising. There is massive and widespread devastation. Hundreds of thousands of people have been rendered without homes. And the ordeal is far from over... heartbreaking tragedies like this are not unique to the Philippines, because the whole world, especially developing countries struggling to address poverty and achieve social and human development, confront these same realities. I appeal to all, please, no more delays, no more excuses. Please, let Doha be remembered as the place where we found the political will to turn things around. Please, let 2012 be remembered as the year the world found the courage, the will to take responsibility for the future we want. I ask of all of us here, if not us, then who? If not now, then when? If not here, then where?"

The negotiators failed to find that courage, however, and COP18 will be remembered as an abdication of responsibility.

On December 7th EU Climate Commissioner Connie Hedegaard appealed to COP President Al Attiyah to bring the various negotiating tracks together into one ministerial meeting. She warned that time was running out for a successful outcome, maintaining that a deal remained possible if the hosts led a renewed effort to bring ministers together. "We don't have a lot of time,' she said. 'Mr President, please send this package to the Ministerial.'

Al Attiyah not only rejected the single ministerial meeting, but gave the puzzling answer, "I have plenty of time, I can sit here for one year, it is you who does not have much time".

President Al Attiyah fails to realise that time is running out for all of us.

The science points to the acceleration of dangerous climate change. October 2012 was the 333rd consecutive month that global temperatures were above the 20th century average. The atmospheric concentration of CO2 has risen by 31% since around 1750, when the industrial revolution began. It's now at the highest levels in 420,000 years.

The effects of climate change can already be seen in extreme weather events across the world. In 2012 Hurricane Sandy left 100 dead; typhoon Bopha devastated the Philippines: the death toll is at 700 and rising. Record flooding in Pakistan and China, torrential rains and flooding in El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua in 2011 ; heat waves in Russia in 2010 ; flooding in the UK in 2009 and 2012; Hurricane Katrina killed 1,836 people in 2005... The list goes on.

The September 2012 report, Extreme Weather, Extreme Prices, commissioned by Oxfam and undertaken by the Institute of Development Studies is unequivocal: these weather events are not isolated, or coincidence. Extreme weather is the "new normal."

Turn down the heat

The report which had the most significant impact at COP18 is: 'Turn Down the Heat: Why a 4° C Warmer World Must be Avoided,' commissioned by the World Bank from Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research and Climate Analytics, released in November 2012.

The report has irrevocably changed the discourse among negotiators, the business community and the media. It is difficult for even climate change sceptics to ignore the findings. After years of being treated as an imagined threat, climate change has finally been ushered into the boardroom.

The report comes not just from a reputable NGO, but from the World Bank, one of the most powerful multinational financial institutions in the world. 'Turn Down the Heat' marks a departure for the World Bank under the new leadership of Dr Jim Yong Kim. Historically the Bank has not been famed for faultless environmental policy. Bruce Rich, Senior Attorney at the Environmental Defense Fund accused them of 'mortgaging the earth.'

The report delivers some alarming and long overdue facts, stating, 'a 4°C world is so different from the current one that it comes with high uncertainty and new risks that threaten our ability to anticipate and plan for future adaptation needs... The 4°C scenarios are devastating...The inundation of coastal cities; increasing risks for food production potentially leading to higher malnutrition rates; many dry regions becoming dryer, wet regions wetter; unprecedented heat waves in many regions, especially in the tropics; substantially exacerbated water scarcity in many regions; increased frequency of high-intensity tropical cyclones; and irreversible loss of biodiversity, including coral reef systems...'

In 1896 Svante Arrhenius, a Swedish scientist, observed that if CO2 levels continued to rise global temperatures would also rise by around 4 degrees Celsius by the end of the 21st century.

Why has it taken us over a hundred years to come to the same conclusion?

'Turn Down the Heat' was a rallying cry. Dr Jim Yong Kim writes in the foreword, 'It is my hope that this report shocks us into action.'

Regrettably the shock was not enough to produce the actions needed at COP18. There was a serious gap between what was being negotiated and what the science requires to keep temperatures under a 2 degree Celsius rise. According to the UNEP Emissions Gap Report even if the most ambitious current pledges from countries to cut emissions are honoured, the atmosphere will likely still contain eight gigatonnes of CO2 above safe levels.

COP18, the Doha 'Climate Gateway'

COP18 was faced with the emissions 'Gaps,' the Kyoto period 'Gap,' the Finance 'Gap.' Negotiators threatened fiscal and climate 'cliffs.' The 'weak and dangerously ineffectual' outcome document, the 'Climate Gateway,' fails to provide solutions for most of these issues.

The workstreams which formed the core of the conference could have been decisive, putting in place the necessary measures to avoid the apocalyptic 4 degree warmer world described in the World Bank report. The urgent issues which should have been resolved in Doha were:

-Agreement to a second period of the Kyoto Protocol, to begin on January 1st, 2013, and lasting for 8 years. Kyoto should have been a legally binding, enforceable CO2 reduction agreement.

-Ensuring Green Climate Fund financing of US$100 billion in assistance pledged by developed nations to developing nations for mitigation and adaptation.

This was the bare minimum negotiators should have accomplished. These were vital measures for supporting the developing world and averting the impending climate catastrophe. The results were extremely disappointing. Kyoto is alive, but barely. The text on the Green Climate Fund is a travesty.

In the long term, world leaders had to address:

-The new, global treaty as proposed in the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action, to be 'adopted' by 2015 and implemented in 2020, this will be too little, too late. We need a global, legally binding climate agreement that is, to quote Christiana Figueres, Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC): 'applicable to all, equitably instituted and responsive to science.'

-An objective and credible review with concrete measures to keep the temperature rise below 2 °C.

-The widening emissions gap

COP18 did not inspire confidence. Achieving a successful draft of a new framework for a global climate deal for all countries in 2013 and 2014, to be adopted at COP21 in 2015 seems unlikely. We're painfully short on details of the new agreement. There are ominous signs of obstacles ahead.

Kyoto Protocol

The first period of the Kyoto Protocol, which will expire on December 31st 2012, set binding targets for emissions reductions - on average 5% greenhouse gas reduction from 1990 levels - for 37 industrialized nations including the 27 nation EU. However the two countries with the highest emissions in the world, China and the US, were never bound under the first period of Kyoto. China, the world's highest emitter, ratified the Kyoto Protocol in 2002 but, as it was considered a developing nation when the treaty was negotiated, was not obliged to reduce emissions. The US, the world's second highest emitter, adopted, but never ratified the Protocol.

While far from perfect, Kyoto remains the only global instrument in existence which requires countries to lower emissions.

We urgently needed a second period of Kyoto to begin on 1 January 2013, for an eight-year duration ending in 2020, to avoid any gap between the end of the first period and the new global agreement.

Kyoto is alive, but barely. A second period was agreed, with some of the original signatories signing on. Shamefully, Russia, Japan, Canada and New Zealand refused to commit to a second period. The New Scientist claims that with the loss of these signatories, Kyoto is symbolic, at best. Fatally weakened, the agreement has been reduced to a mere gesture of goodwill.

Christiana Figueres announced the second period of the Kyoto protocol just after 1 pm Qatar time on the 7th of December, declaring it "an enormous victory".

Was it really an enormous victory? Kyoto, which was far from perfect in the first period, has become a shadow of its former self. It's an empty promise.

Targets needed to be set high, finalised and adopted without further delay. The quantified emissions limitation or reduction objectives (QELROs) for the second Kyoto period should have been ambitious. But commitments have been woefully inadequate.

The Kyoto 2 targets amount to an aggregate of 18% below 1990 levels. They are almost laughably insufficient; well below the range demanded by IPCC scientists.

The EU, Australia and Switzerland signed onto a second period for Kyoto, or 'KP2' as it's known. The EU has committed to reducing emissions by 20% compared with 1990 levels by 2020: emissions are already at -17.5%. These commitments represent about 15% of global emissions. At the risk of stating the obvious, this is not nearly enough.

The EU did offer to scale up its reduction to 30% by 2020, if other wealthy countries also commit. No one has taken them up on the offer so far.

Governments have agreed to 'revisit' these targets in 2014. Negotiators are holding out hope that the new global 2015 treaty will close the gaping holes in the Kyoto commitments. "We did pass the bridge between the old system. We're now on our way to 2015, the new regime," said Connie Hedegaard. "It was definitely not an easy ride. Definitely it also was not a beautiful ride. Definitely it was not a fast ride. But we did manage to cross the bridge."

We needed to do more than cross a 'bridge.' A bridge will not avert catastrophic climate change. Once again, negotiators have shelved the problem for a later date.

Green Climate Fund

The 2009 Copenhagen Accord, the outcome document of COP15, contained a much heralded promise by the EU and nine countries including the US, Canada and Australia to pay the developing world $30bn of "climate aid" by the end of 2012, towards a target of $100bn that must be raised by 2020.

Professor James Hansen of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies observed after COP15 that "The hundred billion dollars a year -- the money that Secretary of State Clinton claimed the United States would raise to give to developing countries -- is vapour money. There's no mechanism for such financing to actually occur, and no expectation that it will."

Professor Hansen was right. In the run up to Doha, the fund failed to meet its first $30 bn target for 2012. Analysis by Oxfam and the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), shows only $23.6bn, or 78%, was committed. And some of that $23.6 bn is simply loans or existing aid dressed up as new money.

Finalising this financing for adaptation and mitigation for the developing world at COP18 was critical. The COP needed to address the finance gap, and put mechanisms in place to transfer the promised $100 bn to the developing world. They spectacularly failed to do this.

Developing countries were calling for $60 bn to be pledged between 2013 and 2015, when the so called "fast-start finance" agreement runs out. The increase was vital for countries vulnerable to the growing impacts of climate change.

President Obama asked Congress for $60 bn to repair the damage done by hurricane Sandy. Developing countries requested the same amount to insulate most of the world from the devastation of climate change.

The final text provided no figure for climate financing for the 2013-2015 period. Furthermore there was no firm commitment on financing for vulnerable countries towards the previously agreed target of US$100 billion per year.

The UK allocated about £1.5bn for the period 2013 to 2015, Germany, France, Denmark, Sweden, Finland and the Netherlands also contributed a total €8.3bn by 2015. Although individual countries made commitments, the EU did not agree to a figure.

The talks ended with only $10 billion on the table. It's a paltry amount compared to what is needed.

Celine Charveriat of Oxfam told a press conference on December 7th: "These [developing] countries are being pressed into accepting the unacceptable. They are put into a horrible dilemma of accepting nothing or being accused of collapsing the UN process. What this is really about is the developed countries not keeping their promises and legal obligations."

The US is accused of being the main culprit among these 'developed countries,' of blocking language in the text which would have enabled the scaling up of climate finance.

President Obama made a commitment to combating climate change in his victory speech in November. He said, "We want our children to live in an America that isn't burdened by debt, that isn't weakened by inequality, that isn't threatened by the destructive power of a warming planet".

The US negotiating position at COP18, and at past COPs has been a stark contrast to these words. There were reports that before the weak COP 18 'Gateway' text was agreed, US chief negotiator Todd Stern, referring to new language on "loss and damage", was heard saying: "I will block this. I will shut this down."

COP18 did approve the 'Multi-Window Mechanism to Address Loss and Damage from Climate Change Impacts,' which will ensure financing to developing countries to repair the "loss and damage" caused by climate change. This is the first time developing countries have received such assurances, and the first time the phrase "loss and damage from climate change" has been enshrined in an international legal document. But yet again implementation is a problem. Where will the money come from? Disaster relief funds or existing humanitarian aid?

Failure of the Conference of Parties

Naderev Saño is not the first person to be reduced to tears during the UNFCCC process. When I was in Bali at COP13, Yvo de Boer cried in the middle of negotiations. An observer commented, "He wasn't just wiping his eyes, he was in floods of tears."

I feel that way about COP18.

I attended the first Earth Summit in Rio in 1992. I went with high hopes, believing change was possible. Since then I have participated at a series of COPs and UN conferences in past years. I have witnessed the UN process at work in Bali, Indonesia; Poznan, Poland; Copenhagen, Denmark; Durban, South Africa, and at Rio +20 in Brazil. None of these conferences have provided a solution to the threat of climate change. My faith in the effectiveness of the multilateral process, the UNFCCC and the UNCSD has been shaken.

The task facing the next COP is a daunting one. So much that should have been decided at Copenhagen, in Durban or Doha, has been tabled again and again for future negotiations. Agreements on Reducing Emissions through Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD), emissions cuts pledges, and financing are moving at a snail's pace. To date the negotiations have been consistently stalled by political and special interests. At this rate, agreeing anything by 2015 is a pipe dream.

If you had told me twenty years ago, at that that first Rio Summit, that by 2012 global carbon emissions would have increased by around 50%, that 1 billion people in the world would be hungry, that fossil fuel subsidies would amount to $1 trillion a year, I would have been horrified.

As Lord Stern states in his latest report, 'The overall pace of change is recklessly slow. We are acting as if change is too difficult and costly and delay is not a problem. The rigidity of the processes under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the behaviour of participants also hinder progress. And the vested interests remain powerful.'

I was appalled by the lack of progress, and deeply disturbed by the powerful special interest being exerted in Doha. The fingerprints of corporate interest were all over the COP18 negotiations. As Alden Meyer, director of strategy and policy, Union of Concerned Scientists said at the conclusion of the conference: "There were some winners here. The coal industry won here, the oil industry won here, you saw on display the power of these industries and their short term profit to influence the governments of the world. This wasn't an environmental summit it was a trade fair to see who would share the spoils as we drill in the Arctic, produce tar sand in Canada and mine coal in Indonesia for China..."

Twenty years after the Rio summit, after 18 years of UNFCCC process, of meetings and negotiations and outcome documents, the COP has not achieved its aims. The consequences could be devastating.

Climate Change

On December 6th, six major NGOs: ActionAid, Christian Aid, Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace, Oxfam and WWF joined forces to issue an 'emergency statement,' saying the Doha talks were on the brink of disaster. "How many more glaring reminders, how many more lost lives, how much more suffering is it going to take for rich countries to accept that this is a planetary emergency?' the statement asks.

We know that even a few degrees temperature rise will drastically change the habitability of the planet and bring about potentially catastrophic changes in water sources, forests, food, health, business... It will affect cities, rural areas, economies, food security and health; the physical shape of the land and coast, every aspect of our lives throughout the developing and the developed world. Climate change will affect everyone everywhere, in every nation and from every socio-economic group - but not in the same way. It will be those in developing countries who will be hit first and hardest by the effects of climate change. The poorest people will suffer most - in both the northern and southern hemispheres. Climate change is an issue of social justice.

Between the 8th and the 12th of July 2012 the melted ice area in Greenland increased from the usual 40% to 97%: a 57% increase over the course of just four days. The National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) issued its annual 'Arctic Report Card' on December 5th 2012. The findings, collated from the research of 141 scientists in 15 countries, are deeply troubling.

'During 2012, a number of record or near-record events occurred in relation to the Arctic terrestrial snow cover,' the report states. 'Snow cover duration was the second shortest on record and new minima were set for snow cover extent in May over Eurasia and in June... over the Northern Hemisphere. The rate of loss of June snow cover extent between 1979 and 2012 (the period of satellite observation) set a new record of -17.6%/decade, relative to the 1979-2000 mean. Also on land, new record high temperatures at 20 m depth were measured at most permafrost observatories on the North Slope of Alaska and in the Brooks Range, Alaska...'

And as NOAA Administrator Jane Lubchenco told a press conference at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union. "What happens in the Arctic doesn't always stay in the Arctic."

Indeed, permafrost currently covers nearly a quarter of the northern hemisphere. Thawing of the permafrost, which could release up to 1,700 additional gigatonnes of carbon into the atmosphere, has not yet been taken into account in climate prediction models.

According to the recent UNEP report, 'Policy Implications of Warming Permafrost,' a warming of 3 degrees will lead to thawing of up to 85% of Arctic permafrost. As well as dramatic environmental consequences, this will have serious economic and societal costs in damage to infrastructure: buildings, roads, pipelines, railways, power lines.

In 2007 the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicted that sea levels would rise 2 mm by 2012. But at present sea levels are increasing at an average of 3.2 millimetres per year. At this rate levels could rise by 1.2m by 2100. Low lying, delta countries and coastlines would be seriously affected; small island states like the Maldives could vanish.

The cause of this warming is clear. According to a new report by the Global Carbon Project, carbon dioxide emissions from industry rose an estimated 2.6% this year. The report states, "Unless large and concerted global mitigation efforts are initiated soon, the goal of remaining below 2C will soon become unachievable."

Between 1990 and 2011 there was a 30% increase in radiative forcing - the warming of the global climate - due to carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases. According to the World Meteorological Association, the levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere reached a new record high of 394ppm in 2011.

The world's most current data for atmospheric CO2 is measured at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii. During March 2012 Co2 concentrations were measured at an average of 394.45ppm. In May 2012, they were at 396.78ppm. In June 2012 some monitoring stations in the Arctic showed the highest ever recorded concentrations of carbon dioxide, in some regions, over 400 ppm.

How long before the rest of the world follows suit?

Bill Hare, one of the authors of 'Turn Down the Heat,' told the Guardian: "We have a climate cliff ... We're facing a carbon tsunami, actually, where huge amounts of carbon are now being emitted at a faster rate than ever. And it's that carbon tsunami that's likely to overwhelm the planet with warming, sea-level rise and acidifying the oceans."

Professor Hansen has long been unequivocal that the safe upper atmospheric level of CO2 is 350 ppm. We're well past that threshold. It has become abundantly clear that the UNFCCC negotiations have been recklessly ignoring the scientific evidence.

After COP18, the outlook is bleak. Leaders and ministers were incapable of making the necessary tough decisions to pull us back from the brink of disaster. How much more evidence of impending catastrophic change do they need before taking action?

I fear for our future, for the future of my child and grandchildren, for future generations, and for the future of the planet.

Civil society

By failing to act, governments are condemning us to fatal climate change. But we mustn't give up. Not all is lost. We don't have to stand idle while they procrastinate and prevaricate.

It is preposterous that after all the effort, money and political grandstanding of the COPs, the responsibility of combating climate change should fall to civil society, young people, grassroots movements. But that is where we stand. In order to preserve the planet we must do everything in our power to 'turn down the heat.' And if governments won't act, then we must.

COP18 was attended by over 7,000 members of civil society from all over the world. There were hundreds of side events and meetings on the margins of the government discussions aiming to encourage action from the private sector: scientists, NGO's, youth movements. It's increasingly clear that the momentum for change will come not from governments and world leaders, but from civil society. As Margaret Meade said, "Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world."

Even the World Bank has overhauled its entire work program in the last year, to move ahead and take action to keep us below a 2 degree temperature rise. Negotiators at COP18 failed to take note.

Qatar took one vital, positive step as UNFCCC host: the organisers made efforts to engage regional Arab civil society, which according to the UNFCCC has resulted in 'unprecedented participation from regional NGOs.' There were dedicated sessions on addressing climate change in traditional Arab communities, referred to as 'Hikma' sessions; 'Hikma' meaning 'wisdom' in Arabic.

The organisers flew in 110 young people from countries such as Egypt, Lebanon, the UAE, Bahrain, Oman and others, and gave them free accommodation in Doha. The Arab Youth Climate movement was launched only 10 weeks before the conference to give Arab youth a voice in the climate change debate. They were a breath of fresh at the conference. Their commitment was evident in their passionate statements at the Hikma session on Wednesday, December 5th. Amira, 19, from Egypt, urged Arab governments to push climate change to the top of their agenda, and to move away from fossil fuels. "We can't eat or drink oil," she said. "I am here to fight for my right to survival," said Merna Ahli, 18.

On Saturday the 1st of December, Doha experienced its first ever climate protest, organised by Doha Oasis (demonstrations are normally illegal in Qatar). The rally was small, composed of around 300 people, many from the Arab Youth Climate movement. The voices of these young people calling for change gave me cause for hope.

The fact remains that our governments have failed us - now we must stand together to address the threat of climate change. The crises we face are global, and we can only solve them through global collective action. We cannot, and must not give up.

The good news is that there are concrete actions we can take to mitigate climate change. That is why, in May 2012, I became Ambassador to the IUCN Plant a Pledge campaign.

Plant a Pledge

The aim of Plant a Pledge is to support the Bonn Challenge target, to restore 150 million hectares of degraded and deforested land by 2020. This is the largest restoration initiative the world has ever seen.

The Global Partnership on Forest Landscape Restoration (GPFLR) has mapped 2 billion hectares of deforested and degraded land across the globe - an area the size of South America - with potential for restoration.

The Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change recognises that "curbing deforestation is a highly cost-effective way of reducing greenhouse gas emissions." Deforestation constitutes nearly 20% of overall emissions, and is accelerating climate change. The world's forests store 289 gigatonnes of carbon in their biomass alone, and can be used as a tool to mitigate climate change. Restoring 150 million acres of forest landscapes could sequester approximately 1 gigatonne of carbon dioxide per year. Plant a Pledge and the Bonn Challenge have never been more relevant.

Restoration of degraded and deforested lands is not simply about planting trees. People and communities are at the heart of the restoration effort, which transforms barren or degraded areas of land into healthy, fertile working landscapes. Restored land can be put to a mosaic of uses such as agriculture, protected wildlife reserves, ecological corridors, regenerated forests, managed plantations, agroforestry systems and river or lakeside plantings to protect waterways.

We launched Plant a Pledge at a press conference at Rio+20 in June 2012, where we announced landmark restoration commitments totalling 18 million hectares. The United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service pledged 15 million hectares, the government of Rwanda 2 million hectares, and the Mata Atlantica Forest Restoration Pact of Brazil, a coalition of government agencies, NGOs and private sector partners 1 million hectares.

On Thursday, December 6th, at COP18, I was delighted to announce new pledges by El Salvador and Costa Rica of 1 million hectares each. This brings us to 20 million hectares, and within reach of 50 million.

BMS Rathore, India's Joint Secretary, Ministry of Environment and Forests, has indicated India's commitment to the Bonn Challenge, in a pre-pledge of 10 million hectares, at the Convention on Biological Diversity, COP11 in Hyderabad. The Meso-American Alliance of Peoples and Forests has indicated their interest in pledging 20 million hectares. We look forward to them formalising their commitment with the GPFLR and the IUCN.

The success of the campaign, and the number of restoration pledges has exceeded all expectations. We've far exceeded the target for pledges for 2012, which was 7 million hectares.

But we still need to persuade governments and others who own or manage land around the world to achieve the Bonn Challenge goal by 2020.

The Plant a Pledge campaign, devised by the IUCN and sponsored by Airbus, aims to do just that. Each pledge at www.plantapledge.com supports a global petition directed at world leaders, calls on governments put pen to paper on the specifics - 'where, when and how?' - to achieve the Bonn Challenge.

Damage to our forests and ecosystems could reduce global GDP by about 7% and halve living standards for the world's poorest communities by 2050. Forests sustain our most basic needs. They are vital for clean air, food, three-quarters of the world's fresh water, shelter, health and economic development. 1.6 billion people, almost a quarter of the world's population - depend on forests for their livelihood. 300 million people call forests their home.

We urgently need to put public pressure on governments, businesses, big landowners and communities to contribute to the Bonn Challenge target. Plant a Pledge is a unique opportunity to renew our forest landscapes now. I urge you all to add your name to the petition at www.plantapledge.com

Our fate and that of future generations depend on it.

Restoration can help lift millions of people out of poverty and inject more than US$80 billion per annum into local and global economies while reducing that 'gap' between the carbon emissions reductions governments have promised and what is needed to avoid dangerous climate change by 11 to 17 per cent. And we will see the benefits not only in our lifetime, but in years to come.

Conclusion

With global climate negotiations foundering, it is through initiatives like Plant a Pledge that we will effect change. Politicians and negotiators have lost touch with reality and the human and environmental cost will be devastating.

COP18 demonstrated that we can no longer put our faith in politicians to make the tough decisions we need to avert catastrophic climate change. They have ignored the greatest challenge we face in the world today.

Naderev Saño appealed to world leaders to take responsibility at COP18. 'Please,' he said, 'let 2012 be remembered as the year the world found the courage, the will to take responsibility for the future we want.'

2012 will not be remembered as the year politicians found courage or the will to turn things around. They didn't live up to the responsibility. Negotiators failed Nadarev Saño, and failed us all. Their actions will not achieve the future we want.

It is now up to us to meet the challenge. In the words of Naderev Saño: 'if not us, then who? If not now, then when? If not here, then where?'