"In general, any education system that highlights achievement and goals above process and attitude is, in my opinion, bad for students." -- Jiang Xueqin

Jiang Xueqin believes that the very best American institutions of learning have "a culture and tradition of openness, diversity, and risk-taking that China must emulate if China is to progress as a society and as a culture."

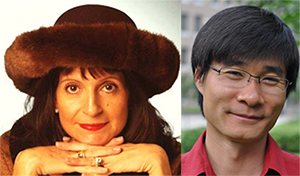

Jiang Xueqin would know; he is a Yale graduate. From 2008 until 2010, he was a curriculum director at Shenzhen Middle School and then deputy principal of Peking University High School. His recently published book, Creative China, is about his experiences in Chinese public schools developing curricula to teach Chinese students creativity and critical thinking skills. A recognized expert on Chinese education, Jiang joins me today in The Global Search for Education East vs. West series.

"Chinese students are focused and disciplined learners who see pain and hard work as fundamental to self-improvement. It seems nowadays that American students put instant self-gratification and high self-esteem above all else." -- Jiang Xueqin

Jiang, how would you define college-ready students in China? What are the skills your higher education system is looking for?

China's Cultural Revolution used education as a steamroller to level the class divisions (especially between intellectuals and the proletariat) that have defined Chinese society for thousands of years. During this period, access to higher education depended entirely on one's family background.

After Deng Xiaoping came into power, education was seen as an important tool in his economic modernization campaign. Based primarily on Soviet Russia's Leninist-Stalinist education system with antecedents in China's keju system, China's examination-oriented system, in which access to higher education was determined by one's performance on a series of national examinations (the gaokao), achieved two major goals. The first and most important was to bring basic literacy and numeracy skills to most of the student population, giving China a young literate workforce that could transition from the fields to the factories (which is what accounted for most of China's economic growth and productivity in the 1980s and 1990s). The second was to filter the students with the highest analytical intelligence to produce a high number of engineers and technocrats to oversee this economic transition as managers and as bureaucrats.

This is to say that the education system exists to serve economic and political objectives in China, and students in China who enter higher education display the follow characteristics: a) Basic literacy and numeracy skills, as well as a solid foundation in history and politics that conforms well to Communist orthodoxy. This is to say that Chinese students are very good at algorithmic tasks and at being micro-managed, but they are not equipped to display critical thinking skills or to work independently; b) Values and attitudes, habits and thinking that permit them to function well and effectively within a Chinese context. This is to say that Chinese students are trained to work very well in factories or bureaucracies, but they tend not to thrive in multi-cultural environments engaged in open-ended projects; c) A fear of authority. This is to say that Chinese students are taught to follow orders and to answer questions, not to give out instructions and to ask questions.

"There is genuine concern among Chinese parents that as China engages the world and as the Chinese workplace puts more emphasis on teamwork, creativity, and independent thinking skills, a Chinese education is failing to prepare students to think independently and to work collaboratively." -- Jiang Xueqin

How much emphasis do you believe your higher education institutions put on test scores versus other attributes and accomplishments? What are your views on this?

In general, Chinese society is obsessed with quantifiable metrics: your salary, the ranking of the school you graduated from, the number of papers you've published as a professor, the number of patents you have, your test score, etc. Currently, the entire emphasis is on a student's test score. It's seen as a reliable, fair, and objective gauge of a student's ability to do well in college as well as the quality of education he has received in school. In the future, college admissions in China will expand to include other metrics, such as the number of scientific papers a student publishes or the number of musical competitions a student wins. In my humble opinion, this really amounts to the same thing, which is to produce and promote a school culture that rewards utilitarian, unethical, shortsighted behavior that destroys a student's intrinsic curiosity, creativity, and love of learning. In general, any education system that highlights achievement and goals above process and attitude is, in my opinion, bad for students.

What can our high schools and higher education institutions learn from yours in China?

Chinese students are focused and disciplined learners who see pain and hard work as fundamental to self-improvement. It seems nowadays that American students put instant self-gratification and high self-esteem above all else.

"Study abroad is a big business in China. The market is saturated with "agencies" that act as go-betweens between American state schools desperate for international students who can pay full tuition and Chinese students looking to study abroad."

-- Jiang Xueqin

Why do so many Chinese students wish to attend undergraduate university programs in the US or the UK?

There are three major reasons for this increasing trend. First, there is genuine concern among Chinese parents that as China engages the world and as the Chinese workplace puts more emphasis on teamwork, creativity, and independent thinking skills, a Chinese education is failing to prepare students to think independently and to work collaboratively. Second, as the economic and political situation in China becomes unstable, the wealthy want to hedge their bets and diversify their assets -- by having their child attend college overseas, it's a good pretext for capital flight as well as a basis for emigration abroad in the future. Third, there is elite segmentation and differentiation -- having a child attend an overseas school is now seen as the equivalent of driving a BMW and carrying an LV handbag in China. And now that the numbers of students studying overseas are so many, there's also a herd mentality taking over.

How do they prepare to become strong candidates for the application process to these schools?

Right now, study abroad is a big business in China. The market is saturated with "agencies" that act as go-betweens between American state schools desperate for international students who can pay full tuition and Chinese students looking to study abroad. Test prep centers make good money making sure that Chinese students achieve the minimum test scores on the SAT and TOEFL required by American schools without actually having to learn how to read and to write in English. At the higher end of the market, to get into the Ivy League, more and more Chinese students are opting for American private high schools (ideally, the traditional feeder schools such as Exeter, Hotchkiss, Lawrenceville, etc.). Unfortunately, there is a herd mentality and follow-the-leader attitude among Chinese students and parents. It's hard to distinguish the very top Chinese candidates from each other (high SAT scores, perfect GPAs, president of student council and general secretary of Model United Nations, summers teaching disadvantaged kids in rural China). That's why Ivy League schools are now opting to trust American private high schools or elite Chinese high schools they know rather than the student himself.

For more information on Creative China

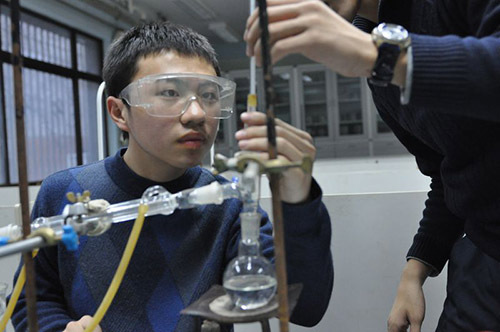

(All photos are courtesy of Jiang Xueqin.)

Join me and globally renowned thought leaders including Sir Michael Barber (UK), Dr. Michael Block (U.S.), Dr. Leon Botstein (U.S.), Professor Clay Christensen (U.S.), Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond (U.S.), Dr. MadhavChavan (India), Professor Michael Fullan (Canada), Professor Howard Gardner (U.S.), Professor Andy Hargreaves (U.S.), Professor Yvonne Hellman (The Netherlands), Professor Kristin Helstad (Norway), Jean Hendrickson (U.S.), Professor Rose Hipkins (New Zealand), Professor Cornelia Hoogland (Canada), Honourable Jeff Johnson (Canada), Mme. Chantal Kaufmann (Belgium), Dr. EijaKauppinen (Finland), State Secretary TapioKosunen (Finland), Professor Dominique Lafontaine (Belgium), Professor Hugh Lauder (UK), Professor Ben Levin (Canada), Lord Ken Macdonald (UK), Professor Barry McGaw (Australia), Shiv Nadar (India), Professor R. Natarajan (India), Dr. Pak Tee Ng (Singapore), Dr. Denise Pope (US), Sridhar Rajagopalan (India), Dr. Diane Ravitch (U.S.), Richard Wilson Riley (U.S.), Sir Ken Robinson (UK), Professor PasiSahlberg (Finland), Professor Manabu Sato (Japan), Andreas Schleicher (PISA, OECD), Dr. Anthony Seldon (UK), Dr. David Shaffer (U.S.), Dr. Kirsten Sivesind (Norway), Chancellor Stephen Spahn (U.S.), Yves Theze (LyceeFrancais U.S.), Professor Charles Ungerleider (Canada), Professor Tony Wagner (U.S.), Sir David Watson (UK), Professor Dylan Wiliam (UK), Dr. Mark Wormald (UK), Professor Theo Wubbels (The Netherlands), Professor Michael Young (UK), and Professor Minxuan Zhang (China) as they explore the big picture education questions that all nations face today.

The Global Search for Education Community Page

C. M. Rubin is the author of two widely read online series for which she received a 2011 Upton Sinclair award, "The Global Search for Education" and "How Will We Read?" She is also the author of three bestselling books, including The Real Alice in Wonderland, is the publisher of CMRubinWorld, and is a Disruptor Foundation Fellow.