The Falling Knight, by John Ruskin (1829)

"Give a horse a nut," says John Ruskin, "and see if he can hold it as a squirrel can."

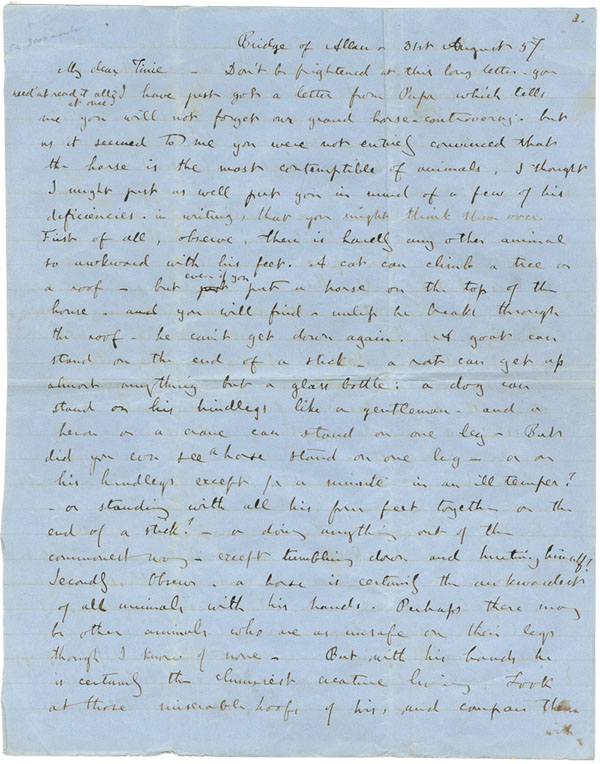

The great English critic was, in the fall of 1857, apparently in the midst of a "great horse-controversy" with Tinie, the young daughter of Ruskin's close friend Robert Horn. It seems that Tinie had recently come to the defense of the horse, and in a very lengthy letter (shown below) Ruskin attempted to convince her that "the horse is the most contemptible of animals."

The first half of the letter is a hilarious catalog of the horse's physical deficiencies, including his hooves, his tail, his eyes, and his nose, each of which Ruskin illuminates by describing what the horse is not. The evidence he gives for the horse being "the most awkward of all animals with his tongue," for instance, is that he cannot sing like a robin; cannot bark or howl like a dog; cannot talk like a parrot. These obvious examples are followed by more and more absurd ones in Ruskin's attempt to leave no doubt in Tinie's mind that the horse is the least of all beasts (and, it seems, to educate her about other animals). He further cites as evidence that the horse cannot catch flies with his tongue, like a chameleon; or ants like an anteater; or fish like other fish -- and he sums it all up by asking: when did you ever see a horse catching fish with his tongue?

Ruskin's final, and lengthiest, point is not about any physical attribute -- it is rather a critical analysis of the role of the horse in fostering social inequality. He segues into the more serious half of the letter by noting, "For you know, if there were no horses there could be no carriages -- of the sort people like to keep. And when you grow a little older, Tinie, you will see, and hear how half the misery that there is in the world just now comes just from people wanting to keep their carriages: And nearly the other half of all the misery in the world comes of people being able to keep them."

This letter was written at about the same time that we can see a general turning point in Ruskin's work: in the late 1850s he was moving away from art criticism toward more social and political commentary. And one of the the most interesting things about this letter is not only Ruskin's interpretation of the horse as a figure of social injustice, but also the way in which he distills the concepts of wealth and social station to points that can be easily comprehended by a child. He is talking to Tinie on her own level, and the letter, which is really more of an essay, is engagingly accessible. His serious points -- that carriages foster pride and indolence among the wealthy, that "horses indirectly helped the superstitions and errors of the middle ages as they did their cruelties," that "all the poor hungry people in the Kingdom" could be fed on what is otherwise spent on racing stables, etc. -- are packaged in such anecdotes and tongue-in-cheek humor that I'm not sure Tinie would have realized she was getting a lesson until she was quite through with the playful missive.

Shown here are just the first two pages of the 3,000 word letter-essay. A partial transcription follows.

First of all, observe, there is hardly any other animal so awkward with his feet. A cat can climb a tree or a roof -- but even if you put a horse on the top of the house -- you will find -- unless he breaks through the roof -- he can't get down again. A goat can stand on the end of a stick -- a rat can climb up almost anything but a glass bottle: a dog can stand on his hindlegs like a gentleman -- and a heron or a crane can stand on one leg -- But did you ever see a horse stand on one leg -- or on his hindlegs except for a minute in an ill temper? -- or standing with all his four feet together on the end of a stick? -- or doing anything out of the commonest way -- except tumbling down and hurting himself?

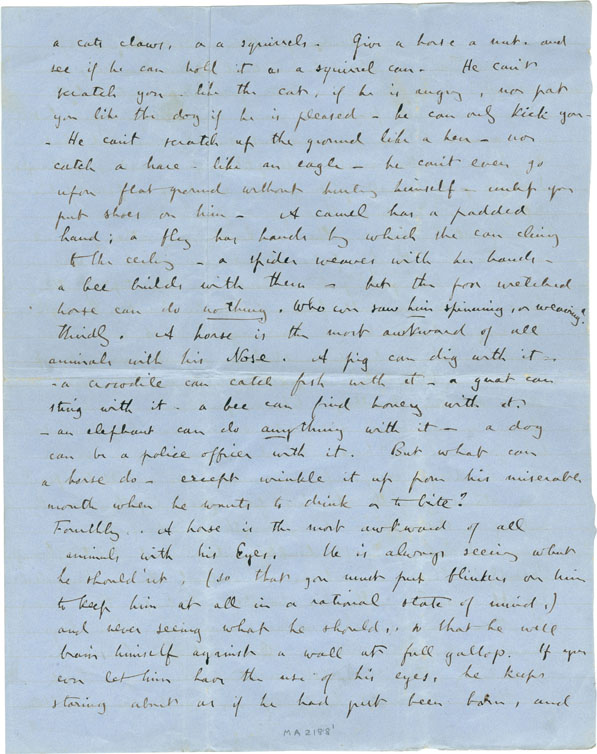

Secondly. Observe -- a horse is certainly the awkwardest of all animals with his hands. Perhaps there may be other animals who are as unsafe on their legs though I know of none. -- But, with his hand, he is certainly the clumsiest creature living. Look at those miserable hoofs of his, and compare them with a cats claws, or a squirrels. Give a horse a nut -- and see if he can hold it as a squirrel can. He can't scratch you -- like the cat, if he is angry, nor pat you like a dog if he is pleased -- he can only kick you -- He can't scratch up the ground like a hen -- nor catch a hare -- like an eagle -- he can't even go upon flat ground without hurting himself -- unless you put shoes on him -- A camel has a padded hand; a fly has hands by which they can cling to the ceiling -- a bee builds with them -- but the poor wretched horse can do nothing. Who ever saw him spinning, or weaving?

Thirdly. A horse is the most awkward of all animals with his Nose. A pig can dig with it -- a crocodile can catch fish with it -- a gnat can sting with it -- a bee can find honey with it. -- an elephant can do anything with it -- a dog can be a police officer with it. But what can a horse do -- except wrinkle it up from his miserable mouth when he wants to drink or bite?

Fourthly. A horse is the most awkward of all animals with his Eyes. He is always seeing what he should'nt. (so that you must put blinkers on him to keep him at all in a rational state of mind.) and never seeing what he should, so that he will brain himself against a wall at full gallop. If you ever let him have the use of his eyes, he keeps staring about as if he had just been born, and looking at straws, and wheelbarrows -- and brooms -- and everything in the world that he has no business with -- as if he had never seen them before in his life.

Fifthly. A horse is the most awkward of all animals with his tongue. A robin can sing -- a dog can bark or howl on proper occasion -- and in an expressive manner -- but when did a horse ever sing to you -- or neigh a thief from your hall door. A parrot can talk with his tongue -- a chameleon can catch flies with it , and an anteater ants -- and there's a fish who can make a fishing rod of his tongue and angle for other fish with it -- but when did you ever hear a horse talk? -- or see him catching fish with his tongue?

Sixthly. A horse is the most awkward of all animals with his tail. A fish can dart with it -- a bird steers with it -- a rattlesnake scolds with it -- a monkey can climb with it -- and a whale can sink a ship with it -- but a horse must have it tied in a knot -- or cut off altogether.

Seventhly -- and in one great count, a horse is the most mischievous of all animals while he is alive and the most useless after he is dead.

For more information about Ruskin's letter to Tinie, click here.