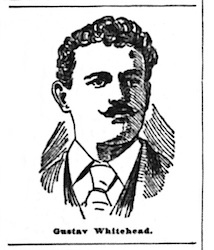

One of the many unresolved stories related to Gustave Whitehead (left) (b. "Gustav Weisskopf" on January 1, 1874, at Leutershausen, Bavaria, Germany, d. October 10, 1927, at Bridgeport, Connecticut) is whether or not he flew in a powered, heavier-than-air machine at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, during 1899.

One of the many unresolved stories related to Gustave Whitehead (left) (b. "Gustav Weisskopf" on January 1, 1874, at Leutershausen, Bavaria, Germany, d. October 10, 1927, at Bridgeport, Connecticut) is whether or not he flew in a powered, heavier-than-air machine at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, during 1899.

"Gus" Whitehead spent a great part of his life trying to build a machine that would fly, although he had one failure after another and never succeeded, he kept experimenting for many years. His numerous failures contrast with the successes of Wilbur and Orville Wright and by 1911 (when he likely saw the professional exhibition aviators flying over Bridgeport, Connecticut), he seems to have given up on his dream of building his own "flying machine." For the last 16 years of his life he increasingly turned to religion.

Popular culture in the 1890s was beginning to latch on to aeronautics as a theme, especially newspapers, literature and pulp publications -- a few examples will serve to put "Gus" Whitehead's efforts in context.

Fiction -- Mystery Airship Hoaxes & Dime Novels

The Great Mystery Airship Scare of 1896 & 1897

In late 1896 the wave of sightings began as 'mystery airships' were reportedly seen in widespread parts of the US, first in the West then they appeared to move East - there were periods when newspapers printed daily reports of sightings.

At the time, there were no known operable airships in the US.

Between November 1896 and July 1897 a great number of 'mystery airship' sightings were reported in 23 states. The reports appeared to be hoaxes or sightings of celestial objects, bored telegraphers sending out fantasy, hoaxing newspaper reporters, sightings of kites or hot-air smoke balloons, or otherwise mistaken interpretations, all of which found their way into print.

At times it seemed one mighty airship was traversing the countryside, stopping once in a while to make "repairs" and occasionally well- or oddly-dressed inhabitants would emerge from the airships to offer explanations or to ask directions. Nude men and women were reportedly seen aloft. One story involved an apparent abduction attempt by weak 7 foot tall creatures. At other times, it seemed many individual airships were appearing hither and yon over the US.

A number of the reports said the mystery airships had searchlights, with which they would scan the sky and the earth below. Nearly all seemed to be buoyed up by very large cigar-shaped gas bags, powered by steam engines driving propellers. Sometimes the airships featured verandas and a conning tower.

Letters were supposedly dropped from above, the contents of which were dutifully reported in the local press. Lawyers told newspapers that their clients were the responsible parties and they would soon announce their intentions and reveal the truth... which never quite came to pass.

Those first seven months of 1897 anyone who read a newspaper would have known that -- possibly -- something thrilling or malevolent or otherworldly was happening.

The reports tapered off then stopped, with only scattered reports in print. What remained, however, was the attention the mystery airships had generated.

The "Invention Fiction" Dime Novels

During the last quarter of the 19th century and into the 1930's, the "Frank Reade" and "Frank Reade, Jr." dime novel series of juvenile "invention fiction" were wildly popular. Steam Age transportation devices were central to the stories, steam and electric powered robot-type men, steam and electric powered airships -- often looking like large naval cruisers with vertical lift propellers and large fan-like propellers at the stern, steam powered boilerplate wheeled war wagons -- many with spikes, steam powered submarines and numbers of other devices were invented by the fictional Frank Reade and later by his fictional son, Frank Reade, Jr.

During the last quarter of the 19th century and into the 1930's, the "Frank Reade" and "Frank Reade, Jr." dime novel series of juvenile "invention fiction" were wildly popular. Steam Age transportation devices were central to the stories, steam and electric powered robot-type men, steam and electric powered airships -- often looking like large naval cruisers with vertical lift propellers and large fan-like propellers at the stern, steam powered boilerplate wheeled war wagons -- many with spikes, steam powered submarines and numbers of other devices were invented by the fictional Frank Reade and later by his fictional son, Frank Reade, Jr.

The Reade family all developed background life stories and all had adventures, including the Reade women, and the dime novels often took place in exotic locations, with some threat or another from "hostiles" (usually native peoples, as the Reades were unabashed imperialists) and large animals.

It would have been next to impossible for anyone then living in the U.S. not to be aware of Frank Reade and the Reade family and their marvelous inventions, including their large metal airships with vertical lift propellers and stern propulsion propellers.

---------------

Science & Reality

Science Amidst The Fantasy

In 1894, the broadly influential Progress In Flying Machines by Octave Chanute was published. In November 1897, Gustave Whitehead took and never returned a copy of that book from the Buffalo, NY, public library. He took other books, as well, including copies of James Means' Aeronautical Annuals, all of which ended up with Whitehead researcher and author Stella Randolph, eventually passing to Whitehead advocate and researcher Maj. Wm. O'Dwyer, who, rather than returning them to their rightful owner, instead gave them to the Gustave Whitehead Museum in Leutershausen, Germany, where they are to this day.

The Means' Aeronautical Annuals, published in 1895, '96 and '97, with a compilation of articles published in 1910, were also influential and served the important roles of spreading awareness of the state of the aeronautical arts as well as providing encouragement to those considering pursuing human flight.

The Means' Aeronautical Annuals, published in 1895, '96 and '97, with a compilation of articles published in 1910, were also influential and served the important roles of spreading awareness of the state of the aeronautical arts as well as providing encouragement to those considering pursuing human flight.

Writing as the "Wright Bros," Orville Wright sent a letter to James Means in 1910 acknowledging the part that the Aeronautical Annuals had played in spurring and sustaining their interest in aeronautics. A clipping from that letter appeared in the 1910 compilation.

Another series of events were amazing those members of the public who were paying attention - the remarkable and successful flights in 1896 and 1899 of Samuel P. Langley's steam-powered, heavier-than-air Aerodromes No. 5 and No. 6.

In May 1896, Aerodrome No. 5 (left) made spectacular circular flights of 3,300 and 2,300 feet, at an altitude of 80 to 100 feet, speeding along at 20 to 25 miles an hour. During November 1896, Aerodrome No. 6 flew 4,200 feet, staying aloft over 1 minute. In June 1899, Aerodrome No. 6 made a circling flight of 1,800 feet, and in July, Aerodrome No. 5 flew 2,500 feet. All of these successful heavier-than-air, powered, sustained flights (without a human aboard) were reported at length in the papers of the day and in popular magazines and journals.

In May 1896, Aerodrome No. 5 (left) made spectacular circular flights of 3,300 and 2,300 feet, at an altitude of 80 to 100 feet, speeding along at 20 to 25 miles an hour. During November 1896, Aerodrome No. 6 flew 4,200 feet, staying aloft over 1 minute. In June 1899, Aerodrome No. 6 made a circling flight of 1,800 feet, and in July, Aerodrome No. 5 flew 2,500 feet. All of these successful heavier-than-air, powered, sustained flights (without a human aboard) were reported at length in the papers of the day and in popular magazines and journals.

In short, during the last few years of the 1890s, the possibility of successful human flight was quite real, and equally as important, the general public had developed a taste for such things.

------------------------------

Gustave Whitehead & His Large Model Airship of 1899

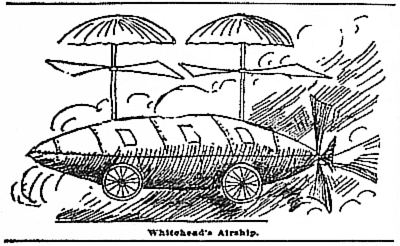

Gustave Whitehead began constructing a large model airship in mid-June 1899 and by mid-July 1899 he was finishing work on his wheeled model aerial craft. The large model airship featured four wheels, two lifting propellers and one pusher "fan wheel" propeller (above drawing from the Pittsburgh Chronicle Telegraph).

The 6 foot long aluminum hull housed two engines within. The larger engine drove the 1,800 rpm "roller scopes" (two 30 inch diameter horizontal propellers) by belts. The rear-mounted 1 foot diameter "fan wheel" for forward propulsion was driven by a "tiny compound engine" and Whitehead expected his model airship would travel at 30 mph. The engines were described as using pressurized acetylene gas for fuel.

The model also sported one 30-inch parachute connected to each upright "roller scope," the purpose of which was to lower the model to ground gently in case of engine failure. Behind the rear "fan wheel" was a rudder for steering left and right. When seen by the reporter, the model airship had no wings and relied solely on the two "roller scopes" for lift.

The large model airship was constructed in about four weeks, and Whitehead told the reporter that he had built 45 "flying machines" and all had been "more or less successful."

Soon after completing his model airship, Whitehead was running the engine which powered the "roller scopes" when a bevel drive gear slipped "doing considerable damage to the machinery."

Almost a week later, Whitehead tested his repaired model airship using "compressed air obtained from the blast furnace through a small pipe in the millyard. A piece of rubber hose was used to introduce the air into the steam chests of the engine." With this arrangement, Whitehead reportedly kept his model airship aloft for 30 minutes. The millyard was likely that of Jones & Laughlin Steel Co., where Whitehead was employed.

Whitehead intended to build a 30 foot long version of the model airship powered by a 20 hp engine, and he estimated it would take him four months to build that machine. Speaking of the full-sized machine, he was quoted as saying "I can finish this machine and with two men can cross the Atlantic in less than 30 hours." Whitehead offered a 50% interest in the machine in exchange for a "few hundred dollars" -- one paper said $800 would be needed.

He had invited reporters from the Pittsburgh Chronicle Telegraph and the Pittsburgh Times to look over his model airship believing that "his small model will show the success of his invention and that he can easily interest capital in the venture."

He told the Times reporter that he can "build on the same principle an airship containing an engine of 1,000 horse power, weighing but 2,000 pounds, and which will carry comfortably from 40 to 50 grown persons."... the absurdity of that statement in 1899 is obvious.

---------------

A Muddled Story -- Darvarich, Galomboshe, Devine, and Ritchey

Gustave Whitehead & The "1899 Pittsburgh Flight" -- The Statements

Louis Darvarich

Louis Darvarich, a friend of Whitehead from 1899 when they both lived in the Oakland section of Pittsburgh, swore in a 1934 affidavit that Whitehead did fly in 1899, and not only that but that he, Darvarich, flew with him...

In approximately April or May, 1899, I was present and flew with Mr. Whitehead on the occasion when he succeeded in flying his machine, propelled by steam motor, on a flight of approximately a half mile distance, at a height of about 20 to 25 feet from the ground.

This flight occurred in Pittsburgh, and the type machine used by Mr. Whitehead was a monoplane. We were unable to rise high enough to avoid a three-story building in our path and when the machine fell I was scalded severely by the steam, for I had been firing the boiler.

I was obliged to spend several weeks in the hospital, and I recall the incident of the flight very clearly. Mr. Whitehead was not injured, as he had been in the front part of the machine steering it.

On its face, the Darvarich statement has some serious problems. He fails to explain how being in the front of a crashing craft and falling 20 - 25 feet would somehow mean that Whitehead was safe from injuries -- a surprising notion. Another problem is that Darvarich cannot nail down the date or even the season of the year that this supposedly happened... in his July 1934 signed statement he says it happened "In approximately April or May, 1899" yet in a letter written in October of that same year, he states "It was in the late fall about three in the afternoon" -- and he gave these conflicting accounts despite his assurance that he recalled "the incident of the flight very clearly."

The language of Darvarich's affidavit was based on at least one earlier interview conducted by Whitehead author Stella Randolph 3 days before Darvarich signed his statement. The typed notes of that interview tell a somewhat different story... in her notes, the "April/May" timeframe relates to an event in Bridgeport, Connecticut, not Pittsburgh. The sentence "It was about April or May I think." is x'd out on Darvarich's statement about Bridgeport and 3 days later is applied to Pittsburgh.

The time in Pittsburgh when we flew, it was a three-story house we flew against and we were up between the third story and the roof when we struck it. It was twenty-five or thirty feet. It was a distance of a half mile we flew there, at least.

Of course I cannot recall now anyone about us. We were not thinking of people, and then the pain I had with my leg after I was scalded made me forget everything else. I was in the hospital some time with it. I will be glad to show you the scar I carry on my body to this day from that flight.

Ms. Randolph refused to take up Darvarich's offer to show her the "scar" on his leg. In Randolph's notes Darvarich does not mention that the machine was a "monoplane" as does his statement signed 3 days later.

Darvarich also told Randolph...

Of course I remember about Mr. Whitehead's flying. I flew with him in Pittsburgh, in the first engine he built (sic). This was a steam engine. I was firing for him. He was so happy that we did not watch our course and we flew up against a building and I was scalded.

Charles Galomboshe

Ms. Randolph also interviewed Charles Galomboshe in July 1934, and her typed notes of that interview state "Did not ever see Mr. Whitehead fly." Galomboshe worked with Whitehead in Pittsburgh during 1899 making propellers for Whitehead. He also stated that...

"I recall starting once to test out a machine, but we struck a bridge and was damaged. We were going about 90 miles an hour, and I got so excited I could not see where we were going. I was doing the steering."

This statement resonates with the better-known Darvarich statement and hints that while an accident might well have happened in Pittsburgh in 1899 -- striking a bridge, likely the "dry bridge" that existed near the intersection of Wilmot and Bates Streets (the Whitehead family lived on Bates St.) -- it did not involve a flying machine but one of what Whitehead called his "automobiles." Whitehead thought a flying machine should have a running start and so his machines had powered wheels, hence his use of the term "automobile."

The recollections that Whitehead's wheeled vehicle hit a newly constructed brick building make more sense if we picture that the powered wheeled vehicle careened out of control at the bottom of the sloping hill on Halket St. while going over the humped dry bridge, clipping the dry bridge's structure and then hitting the brick apartment building on the O'Neil Estate -- which was adjacent to the dry bridge -- not at 20 or 25 or 30 feet up but at ground level.

So, the Darvarich story about hitting the 3 story brick apartment building while in an uncontrolled "flight" might have a basis -- but with a couple significant changes -- Galomboshe in place of Darvarich, and a powered wheeled machine racing down the hill on Halket St. in place of a "flying machine" in flight.

Galomboshe's comments add great weight to the conclusion that Whitehead did not fly in the only finished machine he had at Pittsburgh.

1) Galomboshe stated he was on that first and only test in Pittsburgh with Whitehead, and that he was steering Whitehead's wheeled machine; and

2) Galomboshe stated he never saw Whitehead fly

So, accepting Galomboshe's statements, the only reasonable conclusion is that Whitehead did not fly in Pittsburgh.

Darvarich assigns the cause of the supposed accident to Whitehead being so "happy" he wasn't watching where he was steering. Galomboshe says he was the one steering and that he "... got so excited I could not see where we were going." The similarity of the two accounts is especially interesting when the sequence of Randolph's interviews is considered.

Galomboshe was interviewed by Ms. Randolph on July 15th, the day before Darvarich was interviewed. It's not beyond possibility that Galomboshe and Darvarich spoke to each other prior to their interviews, they had, after all, each assisted Whitehead and knew each other. Also, Ritchey knew Devine -- he was the one who introduced Randolph to Devine. Ms. Randolph's typed notes dated July 17, 1936, begin "It was then late in the afternoon and Mr. Ritchey had already been to see Mr. Devine and told him about my visit and interest in the Whitehead matter."

Martin Devine

Martin "Marty" Devine was 17 years old in 1899 and living in the Oakland section of Pittsburgh, where Whitehead, Darvarich and Galomboshe also lived. He helped push a Whitehead machine "... upon more than one occasion for a demonstration. The plane was heavy and I do not recall being present upon the occasion of its flight but believe I arrived immediately after it crashed into a brick building, a newly constructed apartment house which I believe was on the O'Neale estate. I recall that someone was hurt and taken to a hospital, but do not recall what one." Devine further stated "As definitely as I can recall the plane was upon wheels."

Stella Randolph typed notes dated July 17, 1936, state, in part,

"Mr. Devine could not be sure whether he had seen the flight that crashed; he thought he had arrived on the scene afterward. He remembered the wrecked plane and that a man was scalded and taken to the hospital. He was not a fireman at the time, but hung about the place a great deal and said he had often helped push the plane to give it a start for tests."

According to Randolph's notes, Devine states he did not see "the flight that crashed" yet in his signed statement, Devine states "I do not recall being present upon the occasion of its flight..." It's interesting to ponder that had the machine been flying, Devine might well have heard about it, and the absence of comment that it was flying is, perhaps, an indication that it was not.

Also, in her typed notes, Devine does not say the injured person was "scalded," only that the person was "injured."

Charles Ritchey

As for Charles Ritchey, his recollection was of a machine in Pittsburgh's Schenley Park, a machine that "... was anchored to the ground at the time I saw it."

Ritchey also stated "I do recall of reading about and hearing of this plane making a flight in which it was supposed to have gained a height of about twenty feet and then it crashed injuring the driver."

Randolph's typed notes of July 17, 1936, record that "He said the machine was in a roped off space and was tied down, but that they used to heat up the engine with charcoal for demonstrations, and Whitehead made a little talk to the crowd one day saying that they were going to attempt a flight."

Summary of The Pittsburgh Statements

1) Devine was not witness to a "flight" involving a crash against a brick building;

2) Galomboshe stated the machine hit a bridge while he was steering and made no suggestion that the machine was in flight; and

3) Darvarich was the only person Randolph interviewed in Pittsburgh who claimed that an accident had involved a "flight."

In a 1937 letter to Whitehead researcher and author Stella Randolph, Junius Harworth (youthful assistant to Whitehead in Bridgeport) wrote

"Then about Louis Darvarich. In all the time that I knew him, I NEVER SAW HIM SOBER. [emphasis as in original] Whitehead never took him anywhere under these conditions."

---------------

The Pittsburgh Machines

Did Whitehead make a powered, heavier-than-air, controlled flight in 1899 in Pittsburgh - or any "flight" at all ?

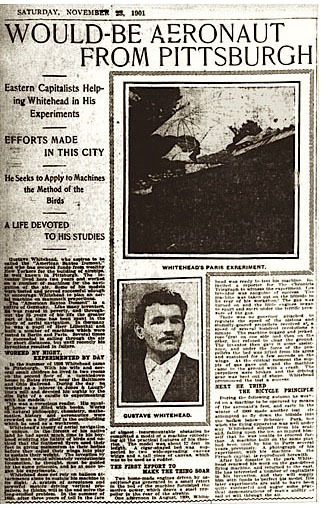

The headline "Would-Be Aeronaut From Pittsburgh" in the Pittsburgh Chronicle Telegraph of November 23, 1901, tells the reader 'no' - he did not, not in 1899, and not in 1901. It seems self-evident that had he flown in Pittsburgh in 1899 or in Bridgeport in August 1901, as has been claimed, that headline would have said so.

That Chronicle Telegraph article provides a revealing glimpse into Whitehead's falsified presentation of his life story, and demonstrates how loose he could be with reality and truth.

Although he was 27 at the time of the 1901 Chronicle Telegraph article, he told the reporter he was 35 years old. He also stated he was a "pupil of Herr Lilienthal" and had gliders which he "tested in Berlin and Paris."

That was, so far as can be determined, the one and only time Whitehead claimed to have made glider flights in Paris, France. It would not, however, be the last time he claimed an association with the great Otto Lilienthal, "The Glider King," and with several other aeronautical luminaries.

Attempts to directly associate Whitehead with Otto Lilienthal have been unsuccessful, and since the Lilienthal brothers kept detailed notes on their activities and associates, it can be reasonably assumed that this claim by Whitehead is false.

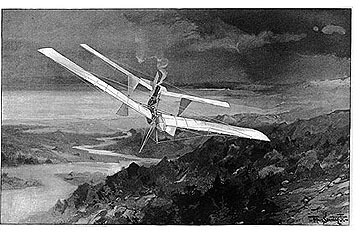

Boston Aeronautical Society glider ca. 1897 misrepresented

by Whitehead as "Whitehead's Paris Experiment."

Likewise, no record has been located placing Whitehead in Paris, France, attempting glider flights. The "Paris" photograph Whitehead provided to the Chronicle Telegraph is almost certainly a photo taken in 1897 of a Boston Aeronautical Society glider experiment, and the person aboard might or might not be Whitehead.

A July 15, 1899, Pittsburgh Post Gazette article mentions Whitehead's claim of having been a "protege of Prof. S. P. Langley of the Smithsonian Institute" and a "former associate of Andree" (S. A. Andree, a noted Swedish balloonist, who mounted a balloon expedition to the Arctic in July 1897 which proved fatal and was a major story in the press of the time) - both of those claims by Whitehead were also false. It is possible that whitehead met Langley through the Boston Aeronautical Society, but Whitehead was most certainly not a "protege" of Langley's.

The Pittsburgh Post Gazette reporter observed "He was a voracious reader. His squalid home was filled with books." "During the day he worked as a laborer at Jones & Laughline's (sic) mill and devoted his nights by the dim light of a candle to experimenting with his models."

The reporter says that Whitehead noticed that birds "...used their feet in giving momentum to their bodies before they called their wings into play to sustain their weight."

What Did Gustave Whitehead Do In Pittsburgh ?

He worked at Jones & Laughlin's Steel Co., as a laborer and "stationary engineer," he pursued money from investors, and he built at least on model airship, one static display machine, one "flying machine," and one glider powered by pedals.

The Chronicle Telegraph reporter states that during the summer of 1899 Whitehead completed a "cigar-shaped" model with "two wide-spreading canvas wings and a tail piece of canvas, to be used as a rudder." The two "home-made" engines were said to be fueled by acetylene gas under pressure, and drove a steel propeller at the rear.

The reporter continues... "One afternoon in August 1899, Whitehead was ready to test his machine. He invited a reporter for the Chronicle Telegraph to witness the experiment. The machine was taken out on the hillside in the rear of his workshop."

The engines were started and "... clumsily-geared propellers revolved at a speed of several hundred revolutions a minute. The machine tugged and jerked, rose first on one side and then on the other, but refused to clear the ground. The inventor then gave it some assistance, and under the force of the propellers the bed [the hull] was lifted from his arms and sustained for a few seconds on the wings." The fuel then ran out and "... the machine came to the ground with a crash. The propellers were broken and the driving gear bent out of shape. Whitehead pronounced the test a success."

Whitehead was to display an aerial vehicle at Pittsburgh's Eleventh Annual Exposition of the Western Pennsylvania Exposition Society held September 6th through October 21st, 1899. It appears that he displayed and operated his model(s) and seems to have had a larger non-operating winged machine on static display. One description of that display machine said it had a hull 19 feet long.

During the winter of 1900/1901 Whitehead experimented with a machine "operated by means of the aeronaut's feet" and during that winter he "attempted to fly down the hillside onto the hollow below Schenley Park, but when the flying apparatus was well under way Whitehead slipped from his seat and, falling upon the ice, so injured himself that was unable to proceed further." This might have been the Schenley Park demonstration and accident that Ritchey referred to in his statement.

The Chronicle Telegraph reporter wrote "After his disaster in the park Whitehead renewed his work on the gas-driven flying machine" and that "He has interested a number of capitalists in his invention, and they will supply him with funds to perfect his model."

Referring to the 1901 experiments at Bridegeport and Faifield, Connecticut, the reporter comments that "His later experiments are said to have been quite successful and augur some practical demonstrations of man's ability to sail at will through the air."

Note that this November 1901 report of Whitehead's "later experiments" - meaning the supposed "flight" at Fairfield three months earlier - are not reported as totally successful - they are said to be "quite successful" and to "augur" - indicate in the future, to portend - "some practical demonstrations" in the future.

The machines built by Whitehead while he lived in Pittsburgh were...

1) a wheeled model flying machine, "Whitehead's Airship," completed in mid-July 1899, that he demonstrated to reporters, 6 feet long with an aluminum hull, 2 parachutes, 2 "rotor scopes," and a "fan wheel" in the rear; this model was damaged on its first test;

2) possibly a static display machine, perhaps displayed at Pittsburgh's Eleventh Annual Exposition, September 1899 (planned to be displayed but unconfirmed);

3) a 14 foot long, bicycle-wheeled winged machine, "The 1899 Pittsburgh Machine," completed in early December 1899, with 2 propellers, 1 at the front and 1 at the rear, this machine was the one said to be destroyed during its first test; and

4) a winged bicycle affair "operated by means of the aeronaut's feet," begun in the autumn of 1900 and completed during the winter of 1900, while giving a demonstration at Pittsburgh's 456 acre Schenley Park, Whitehead fell off the seat and was injured when he struck ice.

Whitehead's 1899 Pittsburgh "Flight" Explained

The 1899 Pittsburgh Machine - The One & Only Test

This larger machine was completed by early December 1899, and was described as having 4 bicycle wheels, 2 in front and 2 in the rear, mounted under the "body" which was some 5 feet long and 2 feet wide, and was likened to a small canvas skiff boat with "slight" poplar ribs. The total length was reported to be 14 feet. Foldable wings, each 14 feet in span, were mounted on either side of "the prow."

Two small steam 6 h.p. engines, each weighing 15 pounds, drove 2 propellers (termed "wings") at 700 rpm, 1 at the front and 1 at the rear, or so it was reported.

The wings were reportedly attached to a post in the prow and "controlled by a lanyon" so the wings could be "up or down or closed." The total surface area of the canvas wings was reported to be 225 square feet, with a 6 foot long canvas tail of 40 square feet used to guide the machine, with the wheels rigged to be steered on the ground. The total empty weight was reported to be 180 pounds.

This wheeled machine would have been the one that was pushed down the Halket St. hill, with Whitehead and Galomboshe sharing the small "boat," and that struck the "dry bridge" then hit the adjacent three-story brick building at ground level... assuming the event happened at all. No confirming evidence has thus far been found.

Had this event been as spectacular as Darvarich claimed, with a flying machine hitting a building at 25 or 30 feet off the ground then crashing to the ground, it seems reasonable to believe that the story would have been in print in several newspapers.

A less remarkable accident, such as this wheeled vehicle rolling downhill hitting a bridge and finally striking a brick building would have gathered less coverage, so it seems.

According to Darvarich in an October 4, 1934, letter (excerpts follow) to Rose Rennison, Whitehead's daughter...

"No attempts were made before this time to try and fly the plane." "The plane was started from the top of a hill. It was only pushed a short way. The down grade was a means of starting without much pushing." "The plane was destroyed."

So, according to Darvarich, this newly completed machine with the small hull was tried only once and was "destroyed." This means that if the event happened in 1899, it happened after the first week of December, after this machine was finished, and not in "April or May" and not in the "late fall."

The old story that Whitehead's "flying" caused the police to tell him to halt his "experiments" and "flights" is probably not true. Whitehead exploded pressure tanks in his backyard during testing - apparently at night - and that would likely have been the reason for police intervention, if they intervened at all. It's hoped that period police records will settle the matter.

Fire Dept. records for the entire year of 1899 have been located and contain nothing that can be construed as involving a "fiery crash" of a flying machine.

So, as 1899 was ending, Whitehead and Galomboshe might have come roaring down Halket Street hill in Whitehead's powered, wheeled "automobile"-type "flying machine," clipped the "dry bridge" near the intersection of Wilmot and Bates streets, and then hit the three-story brick apartment building just beyond at ground level - destroying the machine and giving birth to the false rumor that in 1899, in the Oakland section of Pittsburgh, a "flying machine" had flown into a brick building, and had fallen to earth in a fiery wreck.

(Special thanks are due to John Schalcosky of Odd Pittsburgh for the Pittsburgh Bureau of Fire Report records along with many period articles featured on OddPittsburgh, including the important November 23, 1901, Pittsburgh Chronicle Telegraph article.)