Sally Mann opens her memoir, Hold Still (Little, Brown), by invoking the muese. An outdated word, the meuse is a mark left in the ground after a small animal leaves; the grass or dust bears an imprint of its departed body. The meuse is a natural parallel of photography, a trace left in the world by a person-a photographer's subject, or perhaps the photographer herself. The meuse is not the actual animal, but a mirror of presence, and this difference is important to Mann. She writes of her art, "I needed the truth, or, as a friend once said, 'something close to it.'"

Another distinction important to Mann is that between art made by unexceptional people and that born of unknowable genius. She was moved by the book Art and Fear, which separates 'ordinary art,' made by hard working, everyday people, from that made by masters such as Proust or Mozart. The book says genius is rare, and yet good art continues to be made, as most art is ordinary art.

Mann proudly identifies with this ethos, writing, "Ordinary art is what I am making. I am a regular person doggedly making ordinary art." She does not effortlessly call upon inspiration to provide her with masterpieces, but works tirelessly, with a devoted passion, detailed in her chronicles of the arduous work required for each image, spontaneous and accidental as it may seem. She shoots variations on a single composition for days with a heavy, time consuming view camera, and prints countless versions of the final image in a darkroom, often using antique developing and printing processes requiring a great deal of patience.

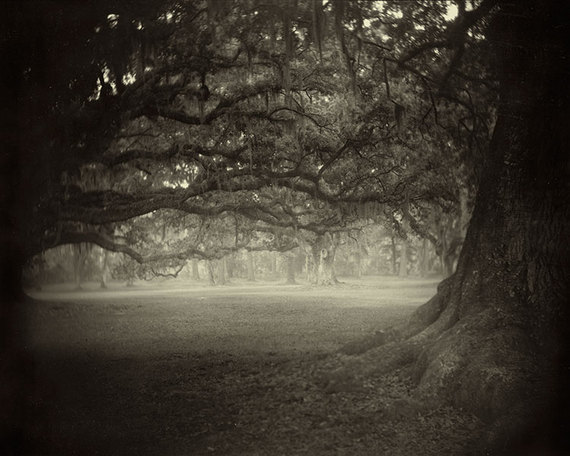

Mann is fascinated by the ordinary, and feels that "part of the artist's job is to make the commonplace singular." Her photographs focus on the South, where she lives. "I began looking for what I had to say where I usually find it," she writes, "in what William Carlos Williams called 'the local.'"

After a series of notorious portraits of her children, she turned to the South for inspiration, photographing landscapes, Civil War battlefields, and her own farm in Lexington, Virginia. She feels a kinship with Southern writers like Faulkner, Welty and O'Connor, and with the music of the South: early jazz and the blues. "We southerners," she writes, "like Proust, have come to believe that the only true perfection is a lost perfection."

The Southern artist she feels closest to is Cy Twombly, who was a neighbor and family friend. Her father collected Twombly's early work, which decorated bookshelves and tabletops in her childhood home. Twombly, too, felt rooted in the South, despite moving to Rome in his late twenties. "It all came from here. All those columns..." he said, "there are many, many things I never would have done if I'd been born somewhere else." Mann recognizes the influence of Southern culture on Twombly's aesthetic and interests, the "chivalric code and the lore of doomed military culture," whose strains can be seen in her own work: photographs of old battlefields, forests and landscapes that look nearly medieval-almost like settings of Arthurian legend. Mann quotes Shelby Foote echoing this sentiment. "We were sick from an old malady, he said: incurable romanticism and misplaced chivalry...We were in love with the past."

She finds another lost word, "hiraeth," helps explain her work. A Welsh term, it means "distance pain," a yearning, a lamentation for a lost place. It also entails a near physical attachment to that place. The Southern landscape is where Sally Mann resides, in daily life, aesthetically, in her work, and in a deeper, spiritual sense. It is not just an artistic subject to her, or a metaphor, or a historically resonant locale. She writes, "the landscape might in fact hold the key to the secrets of the human heart."

Ultimately this hiraeth, this deep longing, the sadness at loss coupled with the knowledge that it is sadness provoked by beauty, is at the root of an artistic legacy to which she feels intimately related. She senses it in Flaubert, who wrote, "The antithesis of everything is always before my eyes. I have never seen a child without thinking that it would grow old, a cradle without thinking of a grave."

She quotes Beckett's Endgame, in which Hamm, trying to console a friend who has gone mad, points out the window to corn growing and ships arriving, saying, "All that loveliness!" But the madman sees it as ruin, and turns from the window. Flaubert and Beckett strike a chord with Mann; she, too, simultaneously sees loveliness and darkness.

Reaching back further than Beckett and Flaubert, she calls upon the aesthetics of Edo era Japan, when the phrase mono no aware was used to describe the intertwining of beauty and melancholy, one depending on the other, neither able to exist alone. Literally translated, mono no aware means "a sensitivity to ephemera." This closely describes Mann's work. Like the meuse, each image derives from an impression that implies the absence of its subject, the beauty of the photograph suggesting sorrow at the loss of the moment it portrays. The children in her pictures are no longer children, their vulnerable, unbridled bodies now changed into self-aware adults.

Mono no aware also translates as "the pathos of things," which suits Mann's work. Her captivating Civil War battlefields, with their lonely trees, delicate as lace on dim horizons, and gracefully curved dusty roads, are graveyards of men who gave their lives defending slavery. She presents them to us like mesmerizing jewels somehow both stunning and terrible to behold.

"For me," she writes, "living is the same thing as dying, and loving is the same thing as losing, and this does not make me a madwoman; I believe it can make me better at living, and better at loving, and, just possibly, better at seeing."