Last fall, I had the pleasure of seeing Jewel perform as part of a spectacular day of fundraising for brain research at the Music Festival for Brain Health in Napa, California. I was instantly transported back to my 17-year-old self, sitting with my brother in a beach town coffee shop that served as our home away from home. Captivated week after week by Jewel's musical storytelling of her escape from a childhood spent in the Alaskan wilderness, my brother and I had no idea that life would imminently transform for each of us, thrusting our family into the untamed wild of the mental health care system.

Jewel would soon be discovered in the coffee shop, quickly becoming a Grammy-nominated artist, an abrupt change from living in her car, unable to afford bottled drinking water. My brother, a newly minted Marine, would soon begin acting strangely, pull away from his family and friends, and ultimately be committed to the first of many long term stays in a psychiatric hospital, where he would be diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia.

Twenty years later, a lot has changed for the nine million Americans like my brother who are living with serious brain health challenges, but not nearly enough.

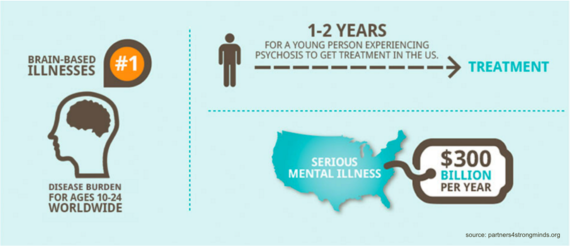

It is now well understood that mental illness is the chief health issue for teens and young adults:

- 1 in 5 teens are affected by a mental health condition.

- 75% of mental illnesses manifest before age 24. Psychiatric disorders are the #1 disease burden for ages 10-24.

- Untreated mental health problems put us at risk for a myriad of life threatening health issues, including suicide, the 2nd leading cause of death for 15-24 year olds in the United States.

Yet, only half of teens and young adults get the treatment they need and deserve.

Oncologists don't wait to see how stage 1 cancer progresses before starting treatment. In the same manner, we cannot afford to ignore 'stage 1' psychosis, ostensibly the most misunderstood brain health condition. Most commonly occurring in teen and young adult years, psychosis impacts the processing of thoughts and sensory information, making it difficult to decipher reality from non-reality. Contrary to popular assumptions, when treated in its early stages with a complementary set of family and social supports, low-dose medication (as needed) and structured talk therapies, the progression of psychosis into a chronic or debilitating condition can be prevented, setting young people up to move forward with their lives in the way they envision.

Based on a large body of international evidence supporting specialty care for early psychosis, highly individualized, empowering treatment is making it possible for young people experiencing psychosis to get back to school, work and chasing their dreams.

If I knew then what I know now, I might have been able to at least question whether changes in my brother's behavior were related to changes in his brain, given a well-established history of mental illness in our family (that, like most families, was rarely acknowledged or discussed). I would have understood the importance of treatment that aimed beyond simply muting my brother's delusions and hallucinations, but also focused on regaining cognitive function and social skills - the things that would have allowed him to retain his identity, confidence and independence.

For my brother, becoming well enough to be discharged from an inpatient unit meant that he was interested in living, and showed fewer outward symptoms of psychosis. However, hospital discharge also came with heavy doses of medication that left him feeling numb, or, in his words, like he was 'constantly drowning,' and included no follow up care. It did not mean he was prepared to go to college, or apply for a job, or regain his friendships; nor did he believe that these things were possible, as we were repeatedly told by his many doctors that they were not.

Around the time our family's journey began with psychosis, early treatment programs began spreading across Europe, Australia and Canada. Two decades later, the United States is finally catching up, with roughly 100 programs offered across the country. A recently published U.S. study underscores the benefits of early treatment for psychosis: significant improvement in symptoms, quality of life and increased involvement in work and school. In 2005, the World Health Organization came to the same conclusion, noting a more than 50% reduction in symptoms for early treatment participants. Now that the clinical landscape is shifting, public awareness about psychosis and its treatability must drastically improve if we are to reach more young people in the early stages of a mental health crisis.

Twenty years ago, early psychosis treatment as we know it today was non-existent in the United States. Today, we know better, and we must do better. The future of 100,000 young Americans who encounter first episode psychosis each year depends on it.

If I could tell the world just one thing

It would be that we're all OK

And not to worry 'cause worry is wasteful

And useless in times like these

I won't be made useless

I won't be idle with despair

I will gather myself around my faith

For light does the darkness most fear

-Jewel