A history lesson lends predictability to a city's efforts to address blight, as well as its likely consequences.

Earlier this week, the Detroit Blight Removal Task Force released a report with recommendations for sweeping away roughly one fifth of Detroit's decaying buildings in the next five years. In preparation, the task force -- created last fall and led by Rock Ventures chairman Dan Gilbert, Detroit Public Schools Foundation president Glenda Price, and U-SNAP-BAC housing corporation executive director Linda Smith -- spent the winter classifying the city's more than 380,000 properties as "blighted" or not.

While "blexting" -- the process survey teams used to text blight conditions into a digital database -- may be an innovative concept, using "blight" as a policy tool to clear the way for large-scale redevelopment of urban areas is anything but new. To understand the implications of blight for Detroit's future, we need to take a look at its history.

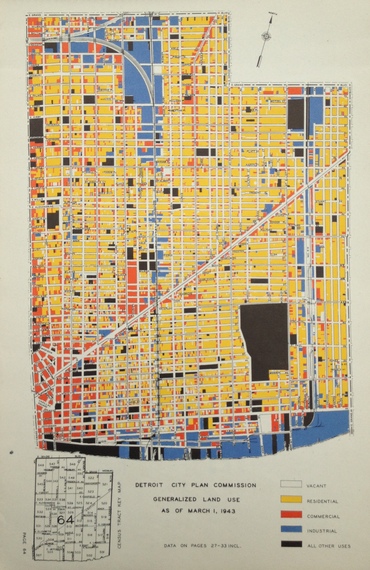

The 1946 Detroit Plan relied on survey data from the early 1940s to document land use by census tract throughout the city. As with the intended impact of the Blight Removal Task Force's 2014 report, these maps informed urban renewal projects in the years that followed (Detroit City Plan Commission, Present Land Use in Detroit: A Master Plan Report, (Detroit, 1946), 64).

What Does It Even Mean?

The term "blight" is intentionally vague. Urban historians and legal scholars have established that it is as much a political and social construct as an empirical condition. Until the 1920s, "blight" appeared in the pages of the Detroit Free Press only to warn readers of plant diseases that could infect their gardens or crops. But the notion soon gained rhetorical influence among housing reformers and politicians across the country who used "blight" to denote other kinds of threats -- perceived material and social pathologies, including those implicitly attached to cities' changing racial and ethnic makeups.

As in many other American cities, whole areas of Detroit were cleared following World War II in the name of "urban renewal." Federal legislation and dollars helped local governments declare entire neighborhoods "blighted," raze them to the ground, and sell the cleared land to private developers, displacing hundreds of thousands of residents in the process. The disproportionate effect on people of color earned urban renewal the moniker "Negro removal." In Detroit, renewal projects included residential high-rises, the expansion of Wayne State University, and the Detroit Medical Center.

To qualify for renewal funds, cities had to first perform surveys -- not unlike those at the crux of the Blight Removal Task Force's report -- documenting that existing homes were in disrepair, lacked hot water or electricity, were overcrowded ... a high level of venereal disease was one accepted marker of community decay. Even a minority of homes that did not meet the standards could in turn "blight" an entire neighborhood as "obsolete" and in need of modernization. As Detroit's Master Plan from 1951 explained,

"In some areas individual buildings are so badly deteriorated, and the general environment so blighted that the areas must be cleared, replanned and rebuilt in a wholesale manner."

Although blight was never precisely defined in law, anxieties about contagion at the root of the word were increasingly applied to the potential for slums (and their dwellers) to spread to other parts of the city. In language that would regularly reappear in the decades to follow, Detroit's master planners feared, "deterioration and blight [were] destroying the city from its core."

Underlying this discourse was a belief that cleared slum land could be put to more "appropriate" use. More appropriate translated as more profitable, which at a time of white flight from cities generally also meant less black. Explained one sociologist in 1965,

"The definition of blight is, simply, that 'this land is too good for these people'... It is an open-ended value judgment, based upon an open-ended aspiration for the given city."

Shown here in 1955, Detroit's Gratiot Redevelopment Project cleared the city's "blighted" Black Bottom area east of Downtown beginning in 1950. The City approved Mies van der Rohe's plan for Lafayette Park in 1956, replacing a poor and mostly African-American neighborhood with a wealthier and whiter housing development. (Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University)

That this term has such lasting power, including defining the work of Detroit's new Blight Removal Task Force, is a testament to its nebulous, ever-evolving quality. The task force created its own definition of blight, which builds on Michigan law (public nuisance, fire hazard, vacant for five consecutive years...) by adding buildings open to the elements and to squatters. Almost half of the 72,000 structures recommended for removal don't quite meet this definition, but nonetheless display what the task force calls "blight indicators" predicting that they will in the future. The task force's description of the perceived risk involved in waiting to find out might as well have come from a half century ago:

"Just like removing only part of a malignant cancerous tumor is no real solution, removing only part or incremental amounts of blight from neighborhoods and the city as a whole is also no real solution. Because, like cancer, unless you remove the entire tumor, blight grows back."

Back to the Future

It may seem obvious today that abandoned buildings in Detroit are "unproductive" and ripe for reuse or demolition, but it is worth recalling the amorphous process of devaluation to which "blighting" is historically tied and its disproportionate impact on people of color.

Although federal urban renewal fell out of favor in the 1960s as the community dislocation and empty promises of revitalization that upheld it became apparent, the practice of documenting poor conditions of urban properties remains widespread. Legal precedents, including mid-century cases that ruled against neighborhood resistance to urban renewal, specifically allow for land declared "blighted" to be seized by the government and then resold to private developers in the name of the public good. Public good, like blight, is itself loosely defined and includes vague promises of economic development or job creation.

Detroit and its Blight Removal Task Force clearly face a different situation than the overcrowding of the postwar period. The city's population today is less than half the size it was in 1950. Once cleared, certain blighted areas may not be rebuilt at all as some planners controversially propose to shrink the city's footprint. Like other cities, Detroit also increasingly relies on private investment rather than federal funding to bankroll redevelopment. But as before, the impetus behind identifying blight remains an effort to engineer a "cleaner" future for the city.

Gilbert, for example, who co-chairs the Blight Removal Task Force, sees an opportunity to revitalize Detroit's downtown by infusing it with billions of his own money and thousands of white-collar professionals from his flagship company Quicken Loans. Gilbert has relocated the company's headquarters to some of the more than forty buildings he purchased in the city's core. Many people welcome Gilbert's capital and his willingness to bet on Detroit's future.

In response to those who say a rehabbed downtown isn't enough to stop the city's decline, the task force report acknowledges that blight is "the physical result of dire economic and social forces that pulled apart the city over many decades," and that going forward, "uneven economic opportunity, poor workforce development, crime, education and spotty public lighting contribute to blight and must be addressed."

Nonetheless, more pernicious mid-century contexts for "blighting" could amplify as the task force recommends -- once again -- how to clear huge swaths of the city's land. Detroit, whose postwar urban renewal efforts failed to stem the exodus of industry and the white middle-class to the suburbs, is now 83 percent black compared to 16 percent in 1950. To Shea Howell, a local activist and professor at Oakland University, the dominant vision of Detroit's future is one in which the new city will -- in an echo of motivations that drove urban renewal -- be "wealthier and whiter."

Howell is among residents who call efforts like those supported by the Blight Removal Task Force's report a "land grab" in which the discourse of blight is strategically employed to devalue the city's property so that private investors can buy it up cheap. They see emphases on "blighting" and its potential to create high investment returns as ignorant of the land's existing richness in community meaning and history for longtime residents.

Blight's malleability as a concept is its greatest legacy. The lessons from the past, including resistance that led to rethinking the top-down approach and discrimination embedded in the postwar federal urban renewal program, suggest that efforts to reshape American cities' landscapes -- both materially and socially -- will not succeed without community buy-in. But the challenge remains to reconcile the "blight" designation's impact on a wide range of stakeholders with the report's call to raise more than $850 million to eliminate tens of thousands of buildings. Today, as before, that plan will require catering to private real-estate interests, sometimes at the expense of alternative definitions of public good.