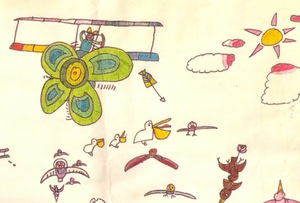

When I was younger, just a boy, I would draw all the time. Constantly. It was how I made sense of the world. What made a cow so like a cow? I drew one. What made cars look like they were moving? I drew one. Airplanes flew, guns shot bullets, waves crashed, buildings had doors, stairs, windows, and people waved, shouted, and floated gently to the earth beneath their parachutes of silk. I couldn't really understand the world, but I understood a line making its way across the page. I understood the object enclosed by a line, the balance of the figure and the ground, the edge of the page and the movement of a story through the still image.

All I wanted was another set of markers. Mine ran out. They were mashed flat to shade the large areas, so they were useless for the detail lines. A new marker was filled with ideas. It had all of the hundreds of drawings it was going to make all coiled tightly in its bright plastic cylinder, ready to be pulled slowly out through the squeaking fiber plug at the end, as it was dragged over a clean white page.

My mother was indulgent. I am sure I had new markers all the time. For a few years the markers came in a box with a simple line drawing of a smiling cartoon face on the front. The smile was huge, and a cutout, so that the markers in the box were the brightly colored teeth of his grin. As I lost or exhausted the colors, the man's grin would wobble, marred by gaps and sloping canines. When he had only a few left rattling in his head I would start lobbying for a new box. One would often show up in the car after a doctor's visit or when I was home sick from school. Oh, the big grin tight with all the rainbow teeth again.

When I drew, the world receded. I knew my father was still dead (a large event in my short life; since he died when I was four it loomed over the rest of my single digit years), and I knew the kids at school were still teasing me because I was short and fatherless, but as the ninety degree arc of yellow filled in the color of the page, the sun lit up a new place, a place no one else controlled or knew about, a place where I made all of the decisions. Before I was ten I drew boats which lumbered out of lakes on wheels. I drew the Irish in an epic aerial battle with the Nazi war aces. In those worlds the worst thing that happened was when the lighter colors smudged the darker ones, causing a rare disconnect between what I saw in my head and what would slowly fill the page.

As I got older, the drawings told fewer stories about people and more stories about machines. There were boats with cars hidden in their bellies, and helicopters ready on deck to hoist them out. There were houses with large wheels on the corners and elaborate cistern systems and filters to allow their occupants to wander afield from the rigid connections of municipal water and sewer. I loved mechanical things and once sat for hours watching the repairmen in the pit of the small passenger elevator in our building in New York.

The more I understood, the more the drawings had to tell. For weeks I worked on drawings of a vehicle for arctic exploration. Page after page for the plan of the living space it would need. The metal treads were wider than the skis in the front for steering. The space for the driver was connected to the living space by a small opening with a sliding hatch so that the two explorers shared the view out the front while the machine glided and grunted over the packed snow.

As I entered puberty (after a two year delay, more short jokes) the machines were sometimes replaced with odd, gangly spiders with Don Martin eyes and Richard Scarry costumes for their occupations. To properly date it, there was a spider speed skater who would have given Eric Heiden a run on the rink, if it had ever managed to escape from my math book. A few cute, alien creatures tumbled down the margins of my composition books, but in high school I started imaging things which were beyond my abilities to draw. And then I took a drafting course.

Mel Gordon looked like the devil. He had just a few wisps of hair left near the back of his head, slicked back with something which made it almost as shiny as his pate. He had thin, high-arching eyebrows. They would curl down over his cinder-black eyes as he explained the twenty different ways we were going to spoil a drawing, before we had even taped the blank sheet to our drafting boards. (The first way was that we were going to tape it down incorrectly.)

He was an old-school instructor from the days of vocational programs. As we toiled over our ninety square inches of bright white paper, he would stalk the aisle between the tables, promising us that he could "see a sixteenth of an inch error, from across the room, on the oblique." My favorite class of the entire year was one where he kicked a student off of her stool and demonstrated, for less than five minutes, how he expected us to be able to draw:

"The page is taped down, there are no wrinkles, I am just picking up the triangle. There's a dusting of eraser bits on the page, so the triangle glides above the paper, it doesn't smudge any of the work I have already put down. I am not moving my hands quickly, but I don't stop moving, either. I'm always getting ready to draw the next line. I do a light enough tick to mark this dimension that I don't need to erase it later, it will become a memory on the page. And when I make these guidelines for the title text, I don't press down on the pencil, I just pull it across the page, the mass of the pencil is enough to give the line the weight I need." He had nearly finished the entire assignment, due in a week, in less than five minutes. He peeled the tape neatly from the corners, pinned it up next to the blackboard, and said, "I didn't do anything that any one of you couldn't do. So get to it."

It was in Mel Gordon's class that the magic happened. He had some artifact. Some piece of a machine. A chunk of metal with a purpose. It had a tunnel through it, a flange, a couple holes for bolts. It was the size of Mel's fist and he held it up against the board. He talked about needing to make it, that somewhere someone had an idea for this piece and they needed to tell someone in the metal shop how to make it. He set the piece on his desk. He pulled down the drafting machine attached to the blackboard, a contraption which provided a straight edge and an adjustable triangle so that he could demonstrate drafting techniques on the board with his chalk in a chalk holder.

"They would need to know what it looked like from the front..." the chalk hissed along the board. "They need to know where to drill the large hole..." hiss, bang, bang, hiss as the chalk danced a center-line for the tunnel. "They need to know about that arc..." bang, squeak as the compass described the arc in the front view. "You would have to dimension this... label that..." He stepped back. There were three views of the piece, a top, front and side, drawn in what I learned was called orthographic projection. With a few dozen lines he had captured reality on the two dimensional black slate.

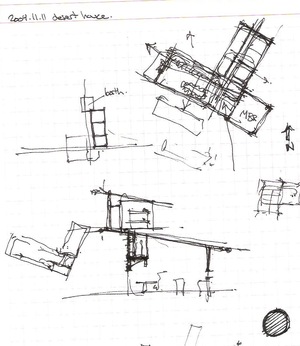

By the end of class we had started our own drawings, each working on a chunk from the metal shop. Mine had a chamfer, a fillet, and a few odd channels. I had blocked out the views and was starting to fill it in. It was very calming, pleasing work. The real world was being mapped to my other, virtual world on the page. The best part of Mel's demonstration, though, was an implication: the drawing came first. We were working backward. This was how to describe things which you wanted to make real.

I know other things happened in high school. I still have the text book from my Physics course. I know that I went to one dance because for the rest of my time in high school I was "the weird kid who showed up on roller skates." I had a friend. So I know things happened, but all that really mattered was the page. Now it could do so much more.

There were all these objects to be described. There were more vehicles, some rockets and planes, but once you understand scale there's really only one thing you want to drawing: buildings.

Buildings have everything.