"You must do the thing you think you cannot do."

--Eleanor Roosevelt, You Learn by Living (1960)

In the aftermath of recent police violence against black men, we look for causes and solutions. And a number of very different stories in the news have me looking to the New Deal and the steady leadership of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt.

One stunning statistic that came out of Baltimore is the unemployment rate for young African American men: 37 percent. The Bureau of Labor Statistics tells us the rate for young white men is 10 percent. Nationally 25 percent of African American young people aged 16 to 19 are unemployed; the comparable number for whites is 4.7 percent. The national numbers for African Americans are the kind of numbers the nation as a whole suffered when Franklin Roosevelt took office in 1933. We remember FDR's first inaugural speech as a message of hope, but we should also remember that FDR was prepared to take drastic action if necessary. He pledged to ask Congress for "broad Executive power to wage a war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe."

Today we face a crisis of the human spirit not unlike that of 1933. Besides the shootings, riots, and demonstrations, there are quieter signs of a deep malaise. For example, in May The New York Times reported on an alarming string of nine suicides since December among young Native Americans on the Pine Ridge Reservation. On June 6 Kalief Browder, a 22-year-old African American man, committed suicide. He had been jailed for three years, often in solitary confinement, without trial. Finally released in 2013, he struggled to overcome despair brought on by the abuse he'd suffered.

These tragedies bring to mind Franklin Roosevelt's argument in the second fireside chat: "To those who say that our expenditures ... are a waste that we cannot afford, I answer that no country, however rich, can afford the waste of its human resources. Demoralization caused by vast unemployment is our greatest extravagance. Morally, it is the greatest menace to our social order."

Unfortunately, demoralization is endemic on the Pine Ridge Reservation, inner-city Baltimore, the jails of New York City, and too many other places in our country. These are hopeless places where young people see only a grim future. Recent social science research confirms their pessimism. As reported in The New York Times, Harvard's Equality of Opportunity Project ranked Baltimore City at the bottom of the nation's 100 largest counties in terms of economic opportunity for low-income children. A child growing up in a poor family there will make $4,510 less (or 17-percent less) at age 26 than a child who grew up in a place with average economic mobility. That same child growing up in Ogala Lakota County, South Dakota, where the Pine Ridge Reservation is located, will fare twice as poorly -- earning $9,040 less (or 35-percent less) than the national average.

In Baltimore, on the Pine Ridge Reservation, and in our prisons, young people are subject to "enforced idleness," which FDR called "an enemy of the human spirit." He spoke in the first inaugural address of "happiness," which "lies not in the mere possession of money; it lies in the joy of achievement, in the thrill of creative effort." That is why he championed work over "relief" or charity. A practical leader, he knew the nation needed -- indeed, its democracy depends on -- putting everybody, including youth, to work. In announcing the National Youth Administration, he repeated the idea: "We can ill afford to lose the skill and energy of ... young men and women."

Today we not only lose the skill and energy of our young people, particularly our young people of color, but we are losing them entirely -- to alienation, prison, and death. Everyone pays the price for their loss, in terms of social unrest, the costs of incarceration and aggressive policing, lost productivity, and especially in the polarization of our people, which is the true enemy of democracy. Instead of recognizing our dependence on one another, we stereotype and stigmatize as we retreat into the apparent safety of partisan political ideology and segregated communities. Once people are defined as a problem to be solved rather than as contributing members of society, when the so-called "solutions" fall short, it is easy to blame the victim and avoid our larger civic and, yes, historical responsibilities. Sustained and effective action to address the twin legacies of America's greatest injustices -- slavery and the genocide of Native Americans -- are moral duties we all share.

Out of the financial emergency of the Great Depression came financial reforms to address the banking and farm and home mortgage crises, and to regulate Wall Street. But at the same time the New Deal addressed the "human crises" of fear, insecurity, and hopelessness. Our 21st-century economy has stabilized since our Great Recession, but for many Americans economic anxiety has grown. We have not taken the needed steps to address our own human crises.

The Civilian Conservation Corps, the first of the New Deal's programs to address unemployment, was enacted in April 1933. By July 250,000 young men were at work in local, state, and national parks, planting trees, clearing roads, and developing natural resources. They were housed and fed in healthy surroundings; they not only improved in morale and physical condition, but they also raised the nation's consciousness about natural resource conservation. Some historians say the training provided to 9 million young men by the CCC was an important factor in preparing them for military service, key to the fighting prowess of the Greatest Generation. They all came from families on relief and earned $30 a month, out of which they were obligated to send $25 home to support their families. In the segregated America of the 1930s, about 200,000 African American men served in 143 segregated camps, receiving equal wages but hardly equal support. There were separate programs to employ Native Americans and veterans. Today we could also use a program to employ those released from prison after their sentences are completed. We have the Jobs Corps, but it serves only about 60,000 annually, a small fraction the young people whom the CCC served. Moreover, it is not a jobs program but a training and education program operated by private contractors that seems plagued with problems.

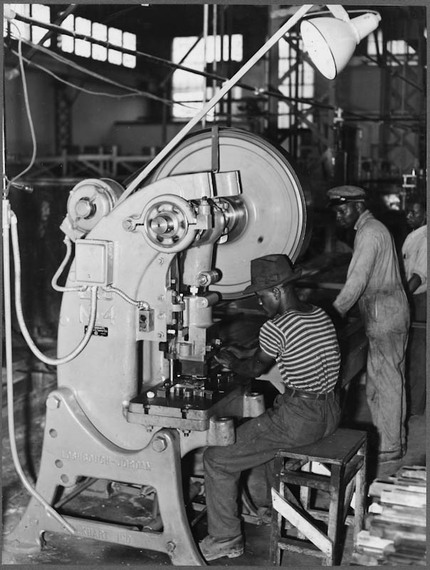

The Works Progress Administration of 1935 ultimately took 8 million unemployed men and women off the relief rolls, providing an opportunity for the dignity of work. Nick Taylor, in his American-Made: When FDR Put the Nation to Work, describes well-known and lesser-known WPA projects that reached nearly every community in the nation, building new parks, roads, schools, and hospitals. There were also sewing rooms, bookmobiles and packhorse librarians, archivists, folklorists, and architects recording historic buildings. The much smaller Federal One program unleashed the creativity of writers, artists, and musicians and nourished the nation's soul. By the time it ended in 1943, the WPA had built 650,000 miles of roads, 78,000 bridges, 125,000 civilian and military buildings, 800 airports, and 700 miles of airport runways. It operated 1,500 nursery schools and served 900 million hot school lunches. Federal One workers gave 225,000 concerts to audiences totaling 150 million, performed plays and performances to audiences totaling 30 million, created 475,000 works of art and 276 full-length books. Thanks to the WPA we have Reagan National and LaGuardia airports, the Pennsylvania Turnpike, and the San Antonio River Walk, to name just a few. Surely we have a need today for a new New Deal to rebuild our nation's infrastructure.

The National Youth Administration put school-aged young men and women to work and helped keep them in school. By 1938 it served 327,000 high school and college youth, who were paid from $6 to $40 a month for "work study" projects at their schools. Another 155,000 boys and girls from families on relief were paid $10 to $25 a month for part-time work that included job training.

Instead of using the government's "power to wage a war against the emergency" (as Roosevelt declared), today, across the political spectrum, our leaders say that we must limit the size of government. Many, echoing a democracy-destroying refrain, say that government is the problem, and too many believe them. If government is the problem, then citizenship, voting, and self-government are devalued.

For solutions today we look to private industry and incentivize "job creation" with promises of "tax relief" that further undermine government's ability to do its work. For example, as reported on May 14, New York has "poured tens of millions of dollars into advertising to push the program, Start-Up New York," which releases participating businesses from the obligation to pay state and local taxes for 10 years. In its first full year of operation, the program created fewer than 100 jobs. How can programs like this possibly address the demoralization of vast unemployment in our most distressed communities? And how can we afford the extravagance of businesses that do not pay taxes? New York is not alone; programs that extend benefits to business for dubious job creation at the expense of other taxpayers are sponsored by localities, states, and the federal government.

The idea of a real jobs program is, of course, politically very out of fashion. Yet this is precisely the time to -- paraphrasing Eleanor Roosevelt -- do the thing we think we cannot do. The alternatives are much worse for our people and our country. How much longer can this nation sustain the level of violence and despair that robs our people of their dignity as citizens? How much longer can our economy be dragged down by the huge costs of treating the effects and not the causes of wasted energies and talents? And, most importantly, how much longer can we sustain the hypocrisy of those who promote false promises of prosperity while ignoring the real needs of our neediest people? Can we really pretend to be a land of opportunity in the face of such inequality? Again, in the words of FDR, this time from his second inaugural address, "The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little."

Today it is not only African American and Native American men and women who are out of work and insecure, but surely they are the most severely affected. If the United States could afford to invest in the dignity and future of its people in the midst of the Great Depression, surely we can do so today.

Echoing the greatest Republican of them all, FDR said, "I believe with Abraham Lincoln, that 'the legitimate object of Government is to do for a community of people whatever they need to have done but cannot do at all or cannot do so well for themselves in their separate and individual capacities.'" The problem is not partisan; it is moral.

If the moral judgment of Franklin Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln is not enough, we should look to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states in Article 23, "Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favorable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment." Led by Eleanor Roosevelt, the United States was one of the 48 signatories in 1948. For that community of people who cannot find jobs "themselves in their separate and individual capacities," we, the rest of the people, must empower and demand of our government a real jobs program. There will always be a need for aid to those who, for reasons of disability, cannot work. But meaningful employment leading to self-sufficiency must be available to the vast majority of the unemployed in this country. It is simply a human right.

We face a national emergency that requires, in FDR's words, "action and action now." We need to summon the political will to create -- for the first time -- an American labor force of committed citizens that reaches across boundaries of class, race, gender, and religion and involves all Americans. Only then can those in despair envision a future in which they and their children live useful lives as contributing members of our society. With that comes hope for the future and the dignity of citizenship in the world's greatest democracy.