There is a home movie that I cannot watch without breaking into tears. And I didn't watch it before this writing. It's like precious jewelry, something to be seen only on the most profound of occasions. In the clip, I'm with my family, four older siblings and Mom, at what I think is a train station. We are all waiting, anxiously, for something. I don't know my exact age, but it had to be before I turned six.

The camera moves, and a gigantic, larger-than-life man enters the shot, wearing a suit and black glasses, fashionable 1969 wear. I hug him around his legs like he's my very own Disney character come to life, and, while I don't remember this particular day, the sensation of my dad's embrace is as fresh and warm as just-baked bread.

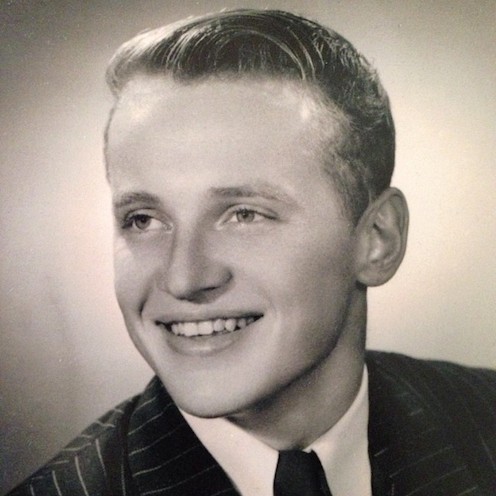

I know I'm no older than five in the clip because that's the age I was when my father killed himself, probably soon after this home movie was made. He jumped off the Benicia Bridge in northern California, two years after he and my mother divorced, and 37 years after being born. Dad was many things: excellent student, attractive as he was popular, captain of the basketball and football team. He married the college homecoming queen and head cheerleader, and they ended up at MIT, where he taught Economics under the tutulage of future Secretary of State George Schultz. He then embarked on a career at Kaiser that took him, finally, to sunny California.

Dad was many other things, too. To protect my family's privacy, I won't go into specific details, but it's fair to say he was often extremely unhappy, and he suffered from severe mental illness for most, if not all, of his adult life. His disease progressed as he got older, he drank more, he got bloated, he lost the sparkle that's so visible in early photographs, he turned violent, he thought people were chasing him.

I witnessed none of this. After my parents got divorced, I saw my father every other weekend, when my two sisters and I got to stay at his Oakland, California, apartment, about 20 minutes from home. We alternated with my brothers, the eldest. Those weekends are encased in a gold leaf box. He would take us to the zoo, or sometimes to a place called Fairy Land, which I don't remember much about except that it was green with lots of water and a windmill and there were rides and Dad was present and brilliant in the light. There was no arguing, there did not exist sadness, in those days life was as it should be, miraculous.

The only memory more wonderful than actual weekends with Dad was when he drove up in a yellow car to pick us up. Later, that car would be found next to the bridge where he took his final look at the world, the car vacant, the motor off, those seat belts that he insisted we use probably unlocked. Mom would announce that Dad was here, and the five of us would run out to the yard, where he'd greet each one of us by picking us up in his arms and swinging us around until we got dizzy. I remember pleading with him to "swing me around," and the waterfall of delights at this recollection blends in with the smell of cut grass, our suburban, happy home yard.

Shortly after my dad's death, a boy approached me in kindergarten class and said, in what seemed like a maniacal tone, "I know how your dad died." I was baffled because I knew how my dad died too. What I didn't know was that, in some circles, suicide was considered something to be ashamed of, a failure, a sin, cowardly. And an act that spreads like fever. Our family was marked, as was my mom, who was even accused of murdering my father, an accusation that came from his mother. Dad's parents' shame at their son's death was not something they could comprehend, and not something they could take responsibility for. She also had a theory that the CIA assassinated him.

On their many unpleasant visits after my father died, the subject never came up. My father's memory was as non-existent as their warmth. My uncle, Dad's only brother, never mentioned him when he and his family would visit. He did spend a lot of time bragging about his children, but my father was never a part of conversation. I never met my dad's sister, but right before she died she called me to talk, to say goodbye to a grown-up nephew she'd never met. I immediately asked her about Dad and she said something about him being wonderful and outgoing and fun and then the phone was taken away from her by one of her children, who told me she was getting weak. She died within a month. I've discovered that, too often, when a family member kills himself, not only does he die but his memory dies with him. On one side of the family, Dad's existence was erased the moment his feet left that ledge.

In my home, my mother talked a lot about Dad's death, made it clear that he loved us very much, and, when questioned as to why he would take his own life, explained that he was very sick and could not get the help he needed. There was never any shame or secrecy in my father's death because it was not presented as shameful or something that needed to be hidden. It was terribly, terribly sad, and I'm usually reminded of my dad when I hear someone talking about losing a parent at a young age due to cancer or some other horrible disease. Years after my dad died, on a bicycle ride with my friend Don, he told me he knew about my father and that someone, probably his mom, wanted to make sure I knew he didn't think less of my family. His intentions were only sincere and his actions very astute for a young child, but I was still puzzled. Everyone seemed to have a problem with how my dad died except me.

I can't speak for anyone else in my family or anyone else who has experienced the suicide of a close friend or relative. I can speak to anyone who refers to suicide as selfish or cowardly, to assure them that, in my case, I never pictured my dad as either. Like my dad, I have suffered extreme mental illness starting at the age of 16, horrifying, crippling, excruciating pain that can only be described as living in someone else's nightmare, because you can't control when you wake up. I knew from a young age that children were out of the question because to possibly expose them to my hell would be an unforgivable offense. Later, marriage was out of the question, as, should my illness strike during the engagement period, I'd be living in forced happiness, pretending to be excited and joyful. Concealing pain is the cruelest sidebar to living with the pain to begin with. Later, my career was out of the question, because you can't pursue your dreams when half of your life is spent climbing a tilted flat cliff with rocks tumbling over your head.

Unlike my father, I never wanted to end my life. In my early 30s, after more doctors than I can remember, I found a drug combination that worked, three different pills that I take to this day, and which are adjusted periodically, with about a 75 percent success rate. For about a month out of each year, I'm in pain. For all of the year, I have no idea when disease will strike. It's like predicting a cold. I'm also extremely lucky because mental illness has achieved greater acceptance, and greater understanding in the medical world, and because I was never encouraged by my mother to hide it or be ashamed of it. If I'm going through a bad spell, I tell my close friends. Talking, I learned years ago, releases the cloud and can sometimes even poke a hole into whatever's contained inside your sealed-up box.

None of my own experiences combined with what I know of my father's life make me think any less of a person who chooses suicide. In this week of unhappy reflection, I've found myself repeating that phrase a lot. Who are any of us to understand what pain another is going through, or to what depths? How do I know that, even if my father had access to the medical advances I've received, he would have survived? There's also the question of mental illness caused by a chemical imbalance versus or combined with despair from another source. Maybe my father's unhappiness was triggered by factors beyond my comprehension. Are any of us in a position to say that every person born to this, admittedly difficult, life is equipped with the tools to survive it? And to that end, know that suicide is always the wrong choice? Perhaps for some it's the only one. When do we stop placing blame and start showing compassion?

We do it now, and, as I learned from a tale of two suicide aftermaths, we don't hide the diseased or the diseases, we don't erase the departed, and we don't relinquish dignity from those who suffered. We learn from them.

We even laugh. About a year back my mother and I got into a giggle fit over the topic of dad's death and strangers. Both of us have had the same experience many times: Is he still alive? "No, he's not." ... When did he die? "1969." ...Oh, I'm sorry. May I ask what he died of? "He killed himself." ... longer pause ... "Oh, I'm so sorry. May I ask how? "He jumped off a bridge." And the conversation stops, the poor stranger blushing and apologizing repeatedly.

After more than 45 years, we deserve a little humor.

Trying to imagine a world with my father in it is like trying to imagine an alternate universe. He'd be 83, and I have no idea if we would have gotten along, if he'd have approved of my homosexuality, of a man who couldn't catch a ball unless Streisand tickets were attached, how his presence would have shaped the lives of my brothers and sisters, if he would have been happy and healthy. He might have remained cruel.

So is trying to imagine a world completely without him. He's in me, in memory and in mind, and my entrance to the world was shaped in huge part by his magnificent existence. I wear his wedding band on my right hand, and, though Mom says she paid about 20 bucks for it, to me it might as well be the Holy Grail. It makes me feel alive to what connects us, and to be reminded that everything I do is in part because of him. I can see it now as I look down at the keyboard. He helped me write this piece.

Need help? In the U.S., call 1-800-273-8255 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.