In a recent New York Times article, scientists argued that certain species might have the genetic makeup sufficient to survive the environmental and climate changes associated with the burning of fossil fuels by human society.

Though likely true this seems to miss the whole point of why people should be concerned about the environmental impacts of our prior and continued use of oil, coal and gas to fuel our economies. Our goldilocks planet -- which orbits the sun in a sweet spot for carbon-based, water-dependent life (not too hot, not too cold) -- has already experienced five prior mass extinctions.

Based on these episodes, our earth seems extraordinarily and even preternaturally resilient. But does that resilience have a limit? Let's take the five extinctions in order:

Extinction event 1

In the transition between the Ordovician and Silurian periods 450 million years ago (Ma), when multicellular life thrived in the earth's oceans and had just begun to colonize the land, 60-70 percent of species were killed off. We believe this happened when tectonic movement of the super continent -- Gondwana -- caused it to pass over the south pole, leading to widespread glaciation and the drying of the continental shelf that supported most marine life.

Extinction event 2

The planet recovered and bony fish evolved and blossomed until, over a 20-million-year period in the late Devonian (375-360 Ma), some 80-90 percent of species died off. All armored fish vanished completely and reef ecosystems did not recover for another 100 million years. We are not sure why this happened, but we do know that during this time the earth had lower levels of oxygen, rising sea levels, and global cooling.

Extinction event 3

By 252 million years ago a single continent, Pangea, spanned the planet from pole to pole causing extremely hot and dry conditions throughout most of the interior. These severe conditions were exacerbated by massive volcanic eruptions over 500,000 years that belched huge volumes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, turning the planet's temperature up even more. As a result, between 93-97 percent of all marine and (this time) terrestrial animals died out. Though many land plants survived, virtually all forests disappeared.

Extinction event 4

The least well understood mass extinction happened at the end of the Triassic around 200 million years ago. In this case, most mammal-like reptiles and amphibians went extinct, reef systems were again annihilated, and over 90 percent of marine species with hard shells like ammonites and clams died off.

Extinction event 5

The last historical mass extinction was likely caused by the impact of a massive extra-planetary object like a comet or asteroid. It struck the earth 66 million years ago and left a 112-mile-wide crater in the Gulf of Mexico. Coming some 140 million years after the previous mass extinction, the earth, resilient as ever, was by then home to diverse and abundant flora and fauna. As a result of this catastrophe dinosaurs died out, as did many early mammals, insects and plants, many species of plankton, ammonites, giant marine lizards, sharks and other fish.

What message can we take from this swift survey of past mass extinctions? Even after losing 60-97 percent of species again and again, nature has rebounded with enough time as new species evolved to populate the seas and continents. In other words, the growing threat of a sixth extinction from climate change would appear to be less of a problem for Earth and more of a problem for ill-adapted fauna and flora.

And yet this time, the actions of our own supposedly intelligent species -- the result of several million years of evolution -- may have set in motion monumental changes that even in planetary time will be hard to recover from.

After past extinction events, populations continued to evolve because they had the genetic variety and physical space to do so. But since the invention of farming 10,000 years ago humans have been transforming the planet and simplifying the rich diversity of nature. With the advent of industrialization in the 18th century, the pace of these changes and loss of nature has only accelerated.

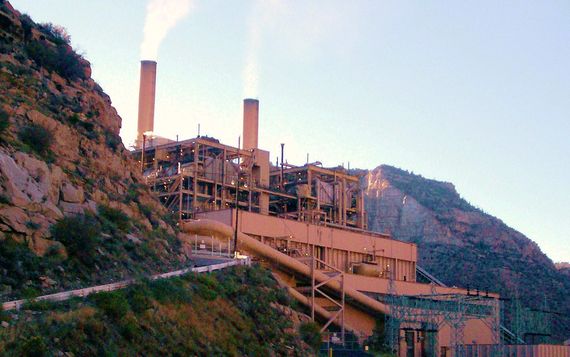

Today 83 percent of Earth's land surface has been impacted by the actions of people. The planet has begun to heat up as we burn more and more oil, gas and coal, releasing huge quantities of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

We need to act now both to preserve our own species and to prevent the loss of the planet's few remaining best wild places -- those increasingly rare areas with intact assemblages of native species that are most resilient and our only manuals for nature. Indeed, unless we take climate change seriously we risk the possibility of a more complete extinction of species than our planet has yet experienced.

Like the dinosaurs, we and our fellow denizens of Earth may become the amber curios of a future civilization that ponders how species once so prevalent came to such a swift demise.