When faced with unlimited choice, do we choose what we know?

I've been experiencing this mild dilemma in miniature with my membership to Spotify Premium. Yes, I've been enticed by the promised of the celestial jukebox, and increasingly chagrined to consider my boxes of old CDs sitting idle in the basement. Who has time, with small children, and jobs, and everything else, to dig through drawers to find a single Ella Fitzgerald song?

Not me. I long ago learned to settle for calling up a scratchy YouTube version of the song I want.

And if not that one, then another.

When I finally succumbed to the $10 per month Spotify Premium fee, I delighted in the possibilities -- oh, the mad possibilities! -- available to me in the age of cloud-based infinite choice. High quality streaming, near instantaneously, of almost anything I might want.

Where to begin! One Direction? Justin Bieber?

I realized immediately, my brain empty (and yes, I recognize that I can indeed check other people's playlists, etc.), some quintessence of the old adage: the child is the father of the man.

Or maybe the stepfather.

Or at least the midwife.

I am not exactly the prisoner of my musical youth; my last book, Blank, incorporated some fantastic DJ Spooky Bach remixes. I do indeed have a healthy interest in newer music. Cue my wife, rolling her eyes. Yet, with Spotify's endless bounty before me, I found myself unable to think of anything new to listen to, and instead, before I quite knew what was happening, I had pulled up the David Bowie catalog...

Bowie's surprise return this week with a new single, "Where Are We Now?" and the promise of a new album in March, The Next Day, spread quickly over the Internet: It's Bowie's comeback. Bowie is not really sick. Etc.

Most interesting is the imagery that comes with this reemergence. The birthday portrait photograph (by Jimmy King) on the Bowie website is taken in front of a Terry O'Neill photograph of Bowie and William S. Burroughs from 1973 (as part of a Rolling Stone photo shoot).

The linkages between the two figures -- aside from Bowie's use of Burroughs-inspired cut-ups in the songwriting process -- extends to almost every aspect of the rock star's spinning wheel of multiple stage identities.

Burroughs' writing was often predicated on the idea that language was a mechanism of social control, and one of the ways to circumvent such control is through the introduction of random linguistic acts. Yes, this idea coalesces in early form through a mosaic strategy in Naked Lunch (the juxtaposition of unrelated images), but it really gets going with the Nova/Cut-Up trilogy (The Soft Machine [1961, 1966, 1968], The Ticket that Exploded [1962, 1967], and Nova Express [1964], and a series of small-press works that extent and explore these methods. As Burroughs wrote to collaborator Brion Gysin: "Take a life. Divide into Five Year Periods. Write in Pain Signs Word Signs. Cut. Concentrate."

Burroughs' spent many years engaging in word, sound, and image experiments -- in part detailed in the how-to manifesto The Third Mind (first published in 1978, with Gysin). Even upon his "return" to traditional narrative in the 1980s, he used the trope of rotating identity as the legacy of his earlier cut-up works. Kim Carsons, for instance, the protagonist of The Place of Dead Roads (1983), might shift "his identity ten times in the course of a day.''

Bowie, quintessential rock chameleon, deploys his personae in a similar fashion. As much as Burroughs' "voice" may assert itself through his different types of texts, Bowie always sounds like an interesting version of himself, regardless of the number of identity shifts. Whether it's the serious moonlight-crooner of "Let's Dance" or the collapsing urbanite of "Panic in Detroit," this mimicry-that-is-not-mimicry proves to be the most-interesting aspect of Bowie's long career: he is more like the always-himself Tom Cruise, then, say, the character-acting Harry Dean Stanton.

When Cruise stars in a movie, we never forget that we are watching Cruise. That kooky Scientologist may be dancing in his underwear, or sporting an eye patch while plotting to kill Hitler, but it's clearly the same guy. Sure, he sometimes tries to make you forget, and that's precisely where it all goes wrong. When Cruise jumps on the couch for Oprah, he seems ridiculous. Why? Because we are slightly disappointed to think this couch-jumping Cruise is the real Cruise, or that he at least wants us to think he's real. That guy, we ask?

Bowie approaches this same problem from a different angle. He knows that we always know it's him, and so the costumes and dresses and personae are just that: props. There is no real Bowie, because it's all self-subverting author-function. We know, therefore, that even his "real" self must be part of the costuming. Whereas Cruise tries to project the real through careful spin, and so stave off any reports suggesting that this self might be less-than-his compelling movie persona, Bowie's antics deny the possibility of the real.

The video for "Where Are We Now?," by Tony Oursler, extends this idea, as well as the link with Burroughs. Bowie's face is projected onto one side of a two-headed doll (or stuffed animal?), and the second head is filled by the projection of an unidentified woman. The doll sits on a desk in what had been identified as Bowie's old Berlin flat, while a screen projection behind them takes us through images of Berlin.

There are complications: the scene occasionally fills completely with the screen projections; a shot of an interior foyer that first appears to be separate from the projection is later shown on the projected screen.

Further, Doll/Bowie's face looks older than 66, and the elegiac and wistful lyric, sung with the text appearing on screen in type font, reinforces this image of fragility. Bowie sings "just walking the dead" and, hmmm, he doesn't look too good...

Wait. Don't order flowers for the funeral just yet. This isn't even The Frail White Duke.

The payoff of the conceit -- and the song's emotional climax -- occurs at approximately 3:05, with the lyric "As long as there's fire," repeated twice. Here, we find a standing-upright Bowie looking comparatively hearty.

Yay! He's alive.

We return to the doll. At 3:30, a pensive seated Bowie looks over the studio. The song ends at 4:08, but the video continues for another 25-plus seconds for the recession of the doll faces. First, the projection of the woman recedes at 4:13, and then Bowie at 4:17. In each case, we can make out additional face and head details of each person as they pull back from the projection space of the doll heads, suggesting that the doll frame is merely that, another shaping mechanism obscuring additional obfuscation. Then, we get a good stretch of seconds where the projection on the screen continues to move over a grey sky, while the doll-face -spaces appear frozen in a similar color.

All of this explicit projection upon projection -- the lyric typeface over and next to the dolls in the studio behind the screen, with "real" Bowie watching, and we, the viewers, watching it all -- is reminiscent, again, of Burroughs' film experiments, particularly with Anthony Balch, and particularly in a short film called "Bill and Tony" (1972).

Burroughs and Balch play with the disjunction between image and sound; they read a Scientology text and a bit of the movie Freaks (1932), with the resulting sound recording superimposed over each person's talking head, and swapped between. The film deliberately manipulates the connection between source and projection.

Further, in a recent retrospective movie, The Beat Hotel (2010), there is a fantastic sequence that describes Burroughs performing a disappearing act using light, projection, beaded curtain, and copious quantities of hashish.

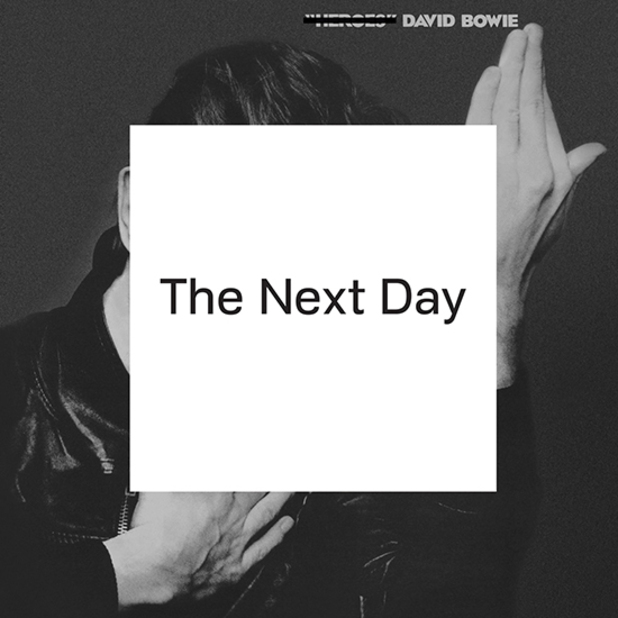

Back to Bowie: the album cover for The Next Day is an erasure of Bowie's cover for Heroes (1977). The title of that record is crossed out, and Bowie's face is replaced by a white square with the album-title text.

This is a type of un-writing, of erasure, that is nothing new for Bowie -- really -- which is precisely what makes it all so damn fun, and so satisfyingly Burroughsian in its levels of distortion, displacement, and juxtaposition.

And the only way Bowie's new work might fail to catch immediate fire is if it were perhaps Tin Machine 2.0; even that, if done with such self-reflective (and projected) cleverness, would still prove delightful, and worthy of continual rotation on Spotify.

Spotify Coda: Yes, I have checked out other music (thank you), but Bowie continues to entice. Here are seven other Bowie songs via YouTube link (in chronological order) worth hearing. And hearing again. These aren't always the deepest of tracks, but they are far from the most obvious. You are free to disagree, and I'm sure you will, but, until then, happy reflecting.

1)"In the Heat of the Morning"

2)"The Bewlay Brothers"

3)"Wild is the Wind" (Nina Simone cover)

4)"Fantastic Voyage"

5)"It's No Game" (Part 1 and 2 are both good; this link is for 2)

6)"Sunday"

7)"Bring Me the Disco King"