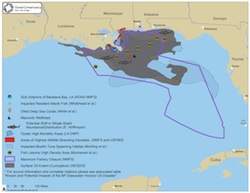

The BP Deepwater Horizon explosion and well blowout was a human tragedy and an environmental disaster. As a nation, we watched in dismay while crude oil spread through much of the Gulf of Mexico, sullying crucial marine environments and stalling economic activity in the region.

In recognizing the second anniversary of that devastating event, we should be reminded of the changes needed in the federal government's approach to oil and gas exploration on the Outer Continental Shelf. Only by changing how we conduct our daily business can we hope to prevent future harm to ocean ecosystems and the people who depend upon them.

In recognizing the second anniversary of that devastating event, we should be reminded of the changes needed in the federal government's approach to oil and gas exploration on the Outer Continental Shelf. Only by changing how we conduct our daily business can we hope to prevent future harm to ocean ecosystems and the people who depend upon them.

We need to decide whether it is appropriate to lease sensitive areas of the ocean for oil and gas development. To make smart decisions, though, we need solid scientific information -- and that information does not exist for most "frontier" areas.

We need to improve efforts to prevent and prepare for offshore oil spills, and this spill planning must incorporate true worst-case scenarios. Oil spill response capacity must be in place and demonstrated to be effective in realistic field conditions.

Baby steps

Despite the disaster in the Gulf two years ago, our nation has taken only baby steps to address these issues. In its January 2011 report, the National Oil Spill Commission highlighted oil and gas leasing in Alaska's Chukchi and Beaufort seas as an area of particular concern -- and it remains so today.

- Containment and response plans proposed by industry must be adequate for each stage of development, and the underlying financial and technical capabilities must be satisfactorily demonstrated in the Arctic;

- The Coast Guard and oil companies should delineate their respective responsibilities in the event of an accident and then build and deploy the necessary capabilities;

- And finally, Congress should allocate the resources to provide Arctic capacity and a physical presence for the Coast Guard, which currently has its closest base about 1,000 miles away.

The damage from a major oil spill in the Arctic would be profound -- not only for the region's vulnerable wildlife but also for its people, whose ways of life depend upon this productive ocean ecosystem.

Despite the risks, the U.S. Department of the Interior has already given initial approval of Shell Oil's plans to conduct exploration drilling in the Chukchi and Beaufort seas this summer. The Interior Department has tightened its requirements in light of the Deepwater Horizon disaster, and other federal agencies have agreed to positive changes, including on-the-water exercises designed to test response processes.

The two key questions, however, are whether the vast leases issued by the federal government are appropriate at all and whether the area can genuinely be protected if a major spill occurs.

The two key questions, however, are whether the vast leases issued by the federal government are appropriate at all and whether the area can genuinely be protected if a major spill occurs.

In the Arctic, the physical conditions under which any response to a major spill would have to be conducted can only be described as severe. If a spill were to begin near the end of the summer drilling season, for example, sustained response activities would encounter Arctic darkness, broken ice, extreme weather and logistical demands that would be among the most difficult on the planet. Response technologies to contain and remove a large spill have never been demonstrated to be effective in the actual conditions encountered in U.S. Arctic waters.

In addition, a 2011 report of the Interior Department's own science agency -- the United States Geological Survey -- identified dozens of science gaps that have not yet been filled. Undeterred by these realities, the Interior Department has given an initial green light to drilling and has placed the risk squarely on the shoulders of the people and wildlife that depend on the Arctic Ocean.

Defining adequate spill response capacity

There is a fundamental disconnect here, and it suggests that we will repeat -- rather than learn from -- crucial mistakes that led up to the Deepwater Horizon oil disaster. When the oil industry and the Interior Department talk about "adequate spill response capacity," they really mean the ability to mobilize oil containment and removal equipment and to make a substantial effort to get oil out of the water or off the shoreline.

But when a major oil spill occurs, the people who are in the path of the spill, as well as most of the rest of us, expect that "adequate spill response capacity" means the ability to contain and remove a large percentage of the spill -- not just a good faith effort that cleans up a relatively small portion of the discharged oil.

After the Exxon Valdez disaster, only about 8 percent of the spilled oil was recovered from the water through response operations; even if the massive on-shore effort is included, the total reaches only 14 percent. Following the Deepwater Horizon blowout, only about 8 percent was skimmed or burned at the surface -- even though the Gulf of Mexico had substantial infrastructure and thousands of vessels participated in the response. In either case, the ability to remove oil released into the environment was very limited.

Because our expectations do not align, we rarely have an honest conversation about the risks and consequences of a big oil spill. Imagine, for example, the difference between the theoretical, on-paper response capacity that exists in oil spill planning documents and the actual, on-water response performance -- especially if that response must be carried out in the dark, amid broken sea ice and in sub-zero temperatures.

The lack of clarity about what response capacity really means makes it more important that we have effective, redundant prevention measures in place. Even more fundamentally, it means that we must make scientifically informed decisions about where drilling is acceptable and where we simply should not lease our ocean for oil and gas exploration because of what would be at risk.

The lack of clarity about what response capacity really means makes it more important that we have effective, redundant prevention measures in place. Even more fundamentally, it means that we must make scientifically informed decisions about where drilling is acceptable and where we simply should not lease our ocean for oil and gas exploration because of what would be at risk.

Perfection is not attainable in oil spill response or in anything else for that matter. But most Americans expect real results -- effective prevention measures and spill response operations that actually recover most of the spilled oil -- not simply a flurry of booms and skimmers and a swarm of boats trying in vain to catch oil.

Without a commitment to significant change, we may feel the same despair we experienced during both the Deepwater Horizon and the Exxon Valdez disasters: anguish about how it could happen and why the response was so ineffective. We've seen the movie more than once, and it's time to write a different ending.

Photos: Cheryl Gerber