It's a saying as old as the game itself and some version of it can be found posted in every Major League Baseball clubhouse: "What we do here, what we say here, when you leave here, it should stay here." It's proof positive of the camaraderie required to play a sport and the trust it takes to bond individuals into a team. To win the war, whether it be on a diamond or battle field, you have to get your teammate's back. Baseball, more than any other game, epitomizes this spirit. With strategies like the "sacrifice" and "suicide squeeze," it's clear where a good player's loyalties lie.

That clubhouse saying would have most certainly carried weight back in the early part of the last century, before ballplayers had agents or a union to speak on their behalf. Long before salaries bloated, players were the property of wealthy owners, who even charged them to launder their uniforms. One team, the Chicago White Sox, was even dubbed the Black Sox because of it. When it was discovered that their uniforms weren't the only things that were dirty, the name stuck.

The notorious Black Sox scandal of 1919 occurred when a group of White Sox players threw the World Series against the Cincinnati Reds in exchange for a promised payoff by gamblers set to bet on the fix. Eight players were consequently banned from baseball for life. George "Buck" Weaver never should have been one of them.

The facts about Weaver's involvement, revealed at the time through court documents, newspaper investigations, witness accounts, and his own testimony, all well-researched ever since, have never wavered. Seven players, including the great "Shoeless" Joe Jackson, either agreed to the fix or received money for it. Buck Weaver stands alone as having done neither. This has never been in dispute. A third baseman, he also played errorless ball during the series, hitting .324, with those hits coming regardless of whether the team was winning or losing.

Weaver was, however present at two meetings with players during which the fix was discussed. In both, he refused to participate. Regardless, the fix went on without him. Games were thrown, money was paid, gamblers double-crossed players who double-crossed each other while both double-crossed the paying public.

The scandal became the flashpoint for outrage against the pervasive influence of gambling that was threatening to destroy the integrity of the National Pastime. At the time, baseball wasn't just a game. Before the advent of movies, it was America's greatest escapist entertainment, with the World Series the Oscars of its day. In an effort to restore the fans' faith, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis was appointed baseball's first commissioner to clean house. His hard line would eventually win that war, but Weaver remains a casualty. Landis's ruling showed no mercy:

"...no player who entertains proposals or promises to throw a game, no player who sits in conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways and means of throwing games are discussed and does not promptly tell the club about it will ever play professional baseball."

But the club already knew. There is evidence that owner Charles Comiskey, among others, knew of the fix, but covered it up in order to protect the financial interests at the gate. While this speaks to the double-standards in Landis's ruling, it does not absolve Weaver of his own responsibility. What does make the ruling untenable is an understanding of American justice. Baseball, after all, is America's Game, and in our system of justice no man who knows of a crime is given the same sentence as the criminals who commission or commit them.

At least one lawmaker agrees. In 2005, the young senator from Illinois wrote to Commissioner Bud Selig asking that the "honorable" Weaver's case be reviewed for reinstatement. (That senator is now our President.) Commissioner Selig responded to Senator Barack Obama's request by assigning Jerome Holtzman, "the outstanding historian of our generation," to research Weaver and report his findings.

Holtzman, a respected author, reporter and inventor of the "save" statistic for relief pitchers, treated the task as sacred. His own sentiments were already on record. "Perhaps now," wrote Holtzman of Weaver in 1992, "the time for mercy has arrived." After his investigation, Holtzman would drop the "perhaps," even going so far as to call Weaver an "innocent bystander."

Then why has no action been taken? Commissioner Selig's own statements seem to imply that he has reservations about overturning the rulings of previous commissioners. (A precedent for reinstatement already exists in the case of the Reds' Ray Fisher, banned by Landis in 1920 and reinstated by Commissioner Bowie Kuhn in 1980.) But anyone questioning the value of reassessing a previous baseball generation's decisions need only know one word: segregation. That heinous policy, instituted in the 1880's, remained in effect until Commissioner Happy Chandler allowed the Dodgers' Branch Rickey to sign Jackie Robinson in 1947. Chandler would write that he did it so that he could "one day meet my maker with a clear conscience."

These days, a conscience is clearly required. If baseball persists in upholding a policy that bans someone for simply knowing of wrongdoing and not reporting it, then they might as well cancel the game. The lineup of players, executives and officials ignoring the illegal use of steroids in recent years would stretch from this country all the way to Toronto.

Commissioner Selig may also worry that reinstating Weaver would open the floodgates to requests for reinstatement for more popular players. But, in terms of innocence, the Reds' Pete Rose, the all-time hits leader, who admittedly gambled on the game as a manager, is not even in the same league. Joe Jackson's case is a bit murkier, with contradictory evidence and statements suggesting both innocence and guilt. (E.g., Jackson received five thousand dollars for the fix which he tried to return, while also complaining about not receiving more.)

There is much in Jackson's case to evoke sympathy and no doubt there will be a huge push to reinstate him in 2019, the centennial of the scandal, but Weaver should not have to wait. Nor should his fate be tied to Jackson's or any of his other teammates as he remains the only player on baseball's ineligible list banned for inaction. Debates about whether Weaver was in a position to turn snitch are moot. He didn't and paid the price with a lifetime ban. Now that that life is over, his sentence should be considered fulfilled. To continue to punish him posthumously along with players who actively committed crimes against the game is egregious overkill. With Senator Obama's '05 letter, it appeared that Weaver would finally be granted the separate trial that he had begged for all along.

So why hasn't The Holtzman Report on Weaver, like the Mitchell Report on steroids and the Dowd Report on Rose, been released? According to a spokesman in the Commissioner's Office, the case is still "under advisement," but "inactive" which would appear to mean it has been tabled without a decision indefinitely. ("Say it ain't so, Bud. Say it ain't so!") It seems a follow-up letter from President Obama is now due. With the blackout on Buck, a cue from the President's own playbook on "transparency" seems appropriate.

Regardless, Holtzman's views may soon be available for all to read. Before he died in 2008, his papers were acquired by the Chicago Baseball Museum which intends to house the as yet uncatalogued documents in its "Jerome Holtzman Library." Founded by Dr. David Fletcher, the passionate crusader behind the ClearBuck.com Web site, the museum, still in the planning stages, will celebrate the rich heritage of Chicago baseball, and Buck Weaver will have his place in that celebration.

At least he'll be in one museum. Having played only nine years, Weaver is ineligible for the Baseball Hall of Fame, which requires a minimum of ten years of service to join its hallowed halls. The numbers he was putting up when his career was abruptly aborted suggest he was on course for consideration. Shoeless Joe, on the other hand, would be a shoe-in. As is, Cooperstown must content itself with Jackson's shoes (in case you were wondering where they were).

They also have a Buck Weaver bat, but it's not really Buck Weaver's. It's a replica used by John Cusack, the actor who played Weaver in John Sayles' film Eight Men Out. But take a walk from the plaques of enshrined players on the circular ramp that leads to the museum's library and there you will see, displayed on the wall, an enlargement of the only authentic thing they have from the real Buck Weaver: one of the many letters he wrote to the Office of the Commissioner, pleading for reinstatement in an effort to restore his good name. This letter, written by hand to Ford Frick in 1953, is poignant for the simplicity of its plea and subsequently doomed result.

But Buck never gave up. He kept trying until the day his heart finally gave out when he died alone on one of the streets of the Chicago town he never abandoned. He is buried there, in a cemetery called Mount Hope, a fittingly named resting place for someone who never lost faith that one day he would receive justice from America's Game.

If "justice delayed is justice denied," then certainly Buck Weaver has been denied justice for far too long. Those with integrity in the game of baseball as well as its true fans should call on Commissioner Selig to reinstate the "honorable" Buck Weaver to the game he loved. Not because he has Hall of Fame credentials, or because he has famous friends advocating on his behalf, but because it's the right thing to do, and the right thing can't wait. It's the only way to heal one of baseball's biggest black eyes. Because what we do here, what we say here, when you leave here, matters.

Note: To read Senator Barack Obama's letter and Commissioner Bud Selig's response, or to learn more about the case for Buck Weaver go to www.clearbuck.com/news.htm

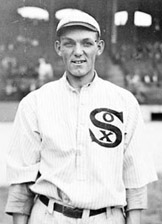

Photo of Buck Weaver at Comiskey Park courtesy Chicago Baseball Museum