Like so many Americans, I spent time with my mom on Mother's Day. Now 83, she is in a nursing home. She spent the last of her savings in less than a year to pay for the nursing care that she needs, so as a family, we had no alternative but to sell her home in 2010. To make ends meet some 20 years earlier when the last of my siblings left for college, Mom had already downsized from the home where she raised her six children.

She did this because she valued her independence. She wanted to live on her own and never wanted to move in with her daughters as her mother and grandma had to do. But staying financially independent in her later years was a challenge. Mom stayed home to raise her children, so she had no retirement savings of her own. No pension, no 401(k) account.

To further complicate her financial situation, she was divorced. Mom found herself in a situation where she had to live on half of my father's Social Security benefit and funds she set aside after the sale of the family home I grew up in. Her situation isn't unique. Women are almost twice as likely as men to live below the poverty line during retirement, and single and minority women struggle the most according to U.S. Government Accountability Office analysis of 2012 Census Bureau data.

Mom knew that her home was critical to her financial security, the last part of the middle class dream she had for her family. She wanted to hang on to it as long as possible. While some economists see home equity is a key part of net worth for elderly households, studies show that most individuals do not tap it. Tapping housing equity appears to be a last resort for older Americans not a solid footing on which to build an adequate retirement income stream.

When I was clearing out her house to put it on the market, I found an old pad of paper with her rudimentary notes trying to calculate how she would stay afloat financially. It was pretty bleak. As a child of the Great Depression, she was conditioned to live as frugally as possible so she could stay in her home and pay her day-to-day living expenses without public assistance. One "luxury" in her budget was daily delivery of the newspaper. But it eventually got to the point that the more expensive Sunday edition was too much of a splurge for her tight budget.

I thought of Mom's situation when I read a recent opinion piece in her favorite newspaper that had some misleading information about retirement.

The author of the column claimed that the median value of $100,000 in IRA or 401(k) accounts of working American households ages 55-64 might be enough if their homes are monetized in retirement. The author cited selected data from Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist James Poterba to make his case, yet failed to mention that Poterba also found a "virtual absence of financial wealth" among half of the so-called young elderly and a reluctance to draw down housing equity, especially early in retirement.

Intrigued, I dug deeper into Poterba's research. He also found that only about 25 percent of the older populations actual benefit from the so-called 'three legged retirement stool' -- pension, individual savings, and Social Security. Instead, Social Security is the sole or primary source of income for most age 65 and older -- just like my middle class Mom.

So if retirees do not monetize the roofs over their heads, what can the typical working households in the 55 - 64 age group retire on beyond Social Security?

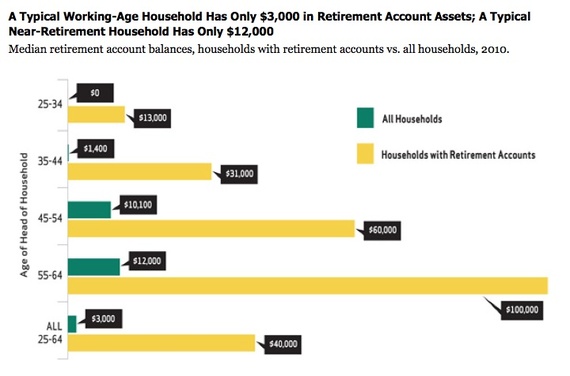

The median $100,000 retirement account balance -- a figure based on the Federal Reserve's Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) data -- just isn't enough. More importantly, that figure is just one small slice of retirement savings picture because it is limited to only that half of the workforce that actually has saved in a retirement plan. In fact, some 38 million working-age households do not have any retirement account assets.

Further analysis of the SCF data covering the retirement savings and overall assets of all U.S. households age 25 to 64, not just those with 401(k) accounts, shows indisputability that the nation is under-saving for retirement. An analysis of the value all households have in retirement accounts finds that nine out of 10 working households do not meet retirement savings targets suggested by Fidelity Investments for their age and income. Even when counting their entire net worth -- including their home equity -- some 65 percent still fall short. More specifically, the typical near-retirement working household, when all households are included, has a median retirement account balance of just $12,000.

Source: National Institute on Retirement Security

Many other organizations have similar calculations. For example, the Urban Institute projects that three out 10 current middle-income workers will likely slide into low-income status by the time they reach retirement. Boston College finds that 53 percent of households are at risk of not having enough to maintain their living standards in retirement.

So what can be done to address the retirement crisis facing not just women, but all Americans? Like Mom, most of the 78 million Baby Boomers entering retirement will struggle to cover basic living expenses -- $19,000 for a single homeowner with no mortgage or $29,500 for a similar couple according to the Gerontology Institute at University of Massachusetts Boston. They need about $4,000 more if they rent.

The way I see it, we have policy choices that could improve the retirement prospect for women and all Americans.

First, do no harm to Social Security. Clearly, the data show that Social Security is a lifeline for the vast majority of retirees. Cutting benefits will force more into poverty, and it makes sense to increase the strength of this safety net in an economically sound manner. Many have recommended expanding this safety net by increasing minimum benefits, which could be of particular benefit to women who will rely on their husband's retirement income.

Second, encourage all women and workers to save by expanding the Saver's Credit. President Obama has directed the Administration to encourage workers without an employer sponsored retirement plan to save through payroll deduction into a myRA. That's a step in the right direction, but the tax benefits to encourage saving are extremely small for many workingwomen. Today, the Saver's Credit provides six million taxpayers an average tax benefit of $170. Covering more workingwomen and households under the Saver's Credit and increasing its value to 50 percent of the retirement contribution would help women build bigger nest eggs.

Third, make retirement accounts available to all women and Americans. Still today, only about half the workforce participates in an employer-sponsored retirement plan. To address this issue, state and federal policy makers are proposing retirement savings programs for private-sector workers to expand access through the workplace. For example, California's Secure Choice Retirement Savings Program would enable employees without an employer-sponsored retirement plan to have automatic contributions deducted from their paychecks go to an Individual Retirement Account. Unless California workers opt out, three percent of their earnings would be invested in a low-fee retirement savings plan with a balanced investment portfolio. Universal access to retirement plans can provide an enormous leg up for women to fortify their financial future.

All moms and women deserve the independence and dignity that is part of the American Dream. Our frayed retirement infrastructure leaves women particularly vulnerable. Don't we owe it to the women in our lives to ensure a strong Social Security and some retirement savings so they can be self-sufficient and enjoy simple pleasure in their elder years?

I'll continue to give Mom one simple pleasure by "splurging" on the Sunday paper I bring every week with I visit her in the nursing home. At this point, the delight is more mine than hers because the haze of dementia allows her to read just a few words.

Photo Credit: istockphoto

Earlier on Huff/Post50: