This post is an excerpt from Diogo Mainardi's upcoming book, The Fall: A Father's Memoir in 424 Steps.

------

Just before he was 6 months old, Tito went for another examination at Padua Hospital.

His neurologist lay him face down on the stretcher. At that moment, he should have rolled over onto his back. Instead, he merely waved his little arms about, but -- like a turtle -- he was unable to turn over.

That was the first sign that he had cerebral palsy.

------

I had found out that my wife was pregnant exactly one year before.

I wrote about it on 23 February 2000 in my column in the magazine Veja.

I started by saying that, up until then, my rejection of fatherhood had been one of the rare, unquestioned certainties of my life. I went on to say that my wish -- and I quote word for word -- was to have "a turtle child, and whenever he became too agitated, I would just have to roll him onto his back and he would lie there, silently waving his little arms."

I got my turtle child.

------

Some days after the examination at Padua Hospital, we received the results through the post. According to the neurologist, Tito had suffered "damage to the extrapyramidal system."

------

I know how to read.

Reading is my job. I think by reading. I feel by reading. When we received the result of the examination at Padua Hospital, I read all about the extrapyramidal system. Nothing I read prepared me for what we were about to discover.

------

Now I know what Tito has.

According to the neurologists who have examined him over the last few years, the damage to his thalamus was caused by his bungled birth. The thalamus is part of the extrapyramidal system. The damage is infinitesimal, so much so that no machine has ever yet managed to detect it. But it's serious enough to affect all his movements.

Tito can't walk, pick things up or talk normally.

------

After examining Tito, the neurologist at Padua Hospital sent him to a physiotherapist at Venice Hospital.

During the weeks that followed, the physiotherapist put him through a series of tests.

It was only when all the tests were over that -- with a feeling of fear and panic -- I first heard the term which, from that moment on, would come to dominate my life.

Tito had cerebral palsy.

------

The fear lasted a week.

Then it passed.

The reason why it took only a week for the fear to pass was a fall.

Tito was sitting on my lap. I was sitting on the sofa in the living room reading the newspaper. My wife, who was rushing about, caught her foot on the rug and fell flat on her face in front of us. When Tito saw her fall, he laughed out loud. We both pretended to fall over. And he laughed and laughed and laughed. And we laughed with him.

Tito's cerebral palsy immediately became more familiar. Slapstick was a language we all understood.

Tito falls. My wife falls. I fall.

What unites us -- what will always unite us -- is the fall.

------

Abbott and Costello Go to Mars: On a voyage into outer space, Lou Costello gets his astronaut's boot caught in a storm drain and falls over when he wrenches it free.

------

Francesca Martinez is a comedian.

She has cerebral palsy. All her performances revolve around that topic.

According to her, the term cerebral palsy can only have been invented to induce "fear and panic." That is why she likes to be described as a "wobbly" person. She is always wobbly, always about to fall.

Francesca Martinez's humor -- like Lou Costello's -- takes its inspiration from her falls.

Cerebral palsy is her astronaut boot caught in a storm drain.

------

Francesca Martinez told the Daily Mail what had happened to her.

Her cerebral palsy, like Tito's, was caused by a medical error. Her mother was left unattended for some hours because "being a Sunday there were fewer hospital staff on duty." Francesca remained in the womb and was left without oxygen for seven minutes.

Cerebral palsy, she explains, "occurs when part of the brain fails to work. It affects one child in five hundred. Each case is unique, but usually people's muscle control and mobility are affected."

The best way to describe how cerebral palsy affects her is that she appears to be "slightly drunk." Her speech is slurred and her balance wobbly.

------

Two weeks after learning that Tito had cerebral palsy, I wrote about it in my column in Veja:

My 7-month-old son has been diagnosed with cerebral palsy. From the outside, that piece of news might seem utterly desperate. From the inside, though, it's different. It was as if they had told me my son was Bulgarian. If I discovered that my son was Bulgarian, the first thing I would do would be to consult a book to find out more about Bulgaria: gross national product, principal rivers, mineral wealth, etc. And that is what I did with cerebral palsy.

------

After saying that cerebral palsy was a term that struck fear into the heart and that, for the first time in my life, I belonged to a minority, I ended the column in this shamelessly sentimental way:

I consider myself to be a humorous writer. For me, there is nothing funnier than frustrated expectations.

Frustrated expectations about social progress.

Frustrated expectations about scientific discoveries.

Frustrated expectations about the power of love.

I have always worked from that anti-enlightenment viewpoint. Now I've changed. I now believe in the power of love. Love for a little Bulgarian.

------

From that moment on, Tito's cerebral palsy became a recurrent theme in my columns.

Over a period of ten years, I devoted eight columns to him.

If, as Francesca Martinez estimated, cerebral palsy affects, on average, 1 child in 500, I published a column on the subject, on average, every 500 days.

Cerebral palsy affected the lives of my readers as often as it affects life in general.

------

In an article in the Daily Telegraph, Francesca Martinez stated: "That's the huge secret about disability -- anyone with experience of it knows that a disabled person is just a person they love."

In my first article about Tito, that was the only "huge secret" I had to reveal.

Astonishingly, for me and for Anna, Tito's cerebral palsy was never a cause for sorrow. Astonishingly, for me and for Anna, Tito's cerebral palsy never seemed a burden.

At 7 months, Tito was simply a person we loved.

------

In mid-2001, we took Tito to see a neurologist in New York.

------

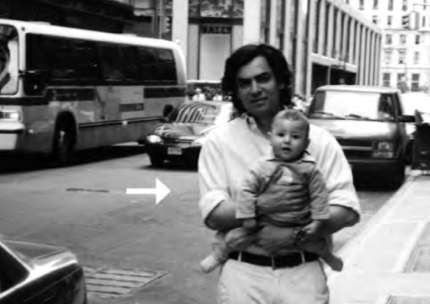

Tito and me in New York.

------

In New York, I became Tito's first mode of transport.

He would point left and I would go left. He would point right and I would go right. He would point at his grandmother and I would hand him over to his grandmother.

Tito would choose my fate by sending me off to the right or to the left.

------

The New York neurologist was very encouraging.

After doing a few tests, he predicted that, in two years' time, Tito would be speaking normally. He also predicted that, in four years' time, Tito would be walking on his own.

Both predictions proved false.

Tito never spoke normally. He never walked on his own.

------

Christy Brown had cerebral palsy.

During the first few months of his life, his parents took him to various neurologists in Dublin.

They all said that Christy Brown would remain forever in a state of "torpor," because he was an "idiot," "mentally defective," a "hopeless case" and "beyond cure."

In his autobiography, My Left Foot, Christy Brown described how he was able to overcome the worst prognoses, finding a way of typing and painting with the big toe of his left foot.

------

Like Christy Brown's parents, Anna and I learned to ignore all the doctors' stupid prognoses, whether positive or negative. Like Christy Brown's parents, Anna and I learned to celebrate each step taken by Tito, however wobbly.

After a certain point, we even learned to celebrate his falls. In the early years, Tito would always hurt himself when he fell. Over time, he developed new ways of breaking his falls.

Knowing how to fall is much more valuable than knowing how to walk.

Like Us On Facebook |

Like Us On Facebook |

Follow Us On Twitter |

Follow Us On Twitter |

![]() Contact HuffPost Parents

Contact HuffPost Parents

Also on HuffPost: