Co-authored by Ellen M. Snyder-Grenier

By 1943, the United States is embroiled in World War II. To meet the urgent demand for ships and heed President Franklin D. Roosevelt's call to hire African Americans for war jobs, Chester, Pennsylvania's Sun Shipbuilding -- located just below Philadelphia on the Delaware River waterfront and one of the largest facilities in the nation -- opens up a segregated yard: "Yard No. 4."

Some see it is progress. It means 6,200 jobs for African American workers. Others say it is a step backwards -- that it makes segregation look like a workable solution for American society. "[It would be] an industrial utopia... wherein 9,000 race workers are to hold every job and execute every task," says Emmett Scott, former Booker T. Washington chief aide, who helped Sun Shipbuilding create the segregated yard. Earl Dickerson, an African American member of the Fair Employment Practices Committee, disagrees. "I would rather see 10,000 Negroes out of work in Philadelphia," he counters, "than to have those 10,000 work in a separate place."

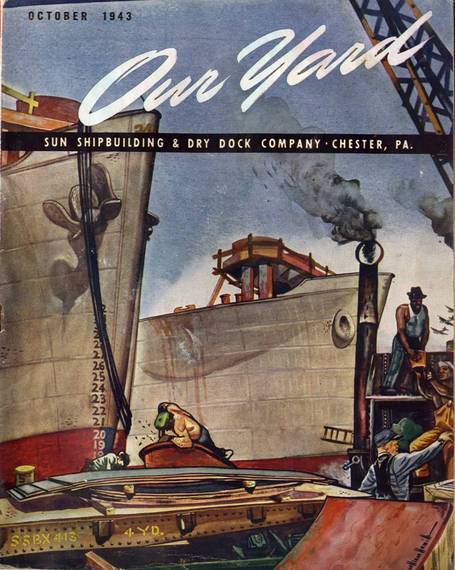

Even as arguments over the segregated yard continue, Yard No. 4 employees build and launch ships crucial to the war effort. The October 1943 cover of Our Yard pictured above, Sun Shipbuilding's company magazine, celebrates their efforts. Workers lean into the urgent job at hand as they make the mighty Marine Eagle rise on the Delaware River waterfront. It is the first ocean-going ship built entirely by African Americans, and a proud chapter in a centuries-old shipbuilding tradition along the lower Delaware.

Sun Shipbuilding also had integrated yards. But the symbolism of its segregated yard, No. 4, was particularly charged in this era. The United States had joined the Allies to fight for freedom overseas. And yet, as Yard No. 4 so clearly demonstrated, African Americans still lacked full freedom and citizenship. Segregation existed on the home front; at the front; and even in the places where those two worlds intersected -- like the USO. In Philadelphia, there were two: one for white sailors and soldiers; another for African Americans of the same status. When in 1945 an African-American serviceman danced with a white hostess at the city's white USO, he was told that is "was no place for a colored soldier, and that he should go to the Negro Canteen." He responded, said a 1945 report on the incident, "that he had been fighting overseas for 3 years, and thought he was fighting for democracy."

Not surprisingly, when World War II ended in 1945, the last hired were the first fired. Sun Shipbuilding's Yard No. 4, which had employed thousands of African-American workers, closed.

Yard No. 4 represented the crux of Jim Crow. The Civil War ended in 1865, but enslavement's shadow had not faded easily. Instead, it gave birth to discrimination. When the 1896 Supreme Court upheld segregation and the doctrine of separate but equal set forth in Plessy v. Ferguson, Jim Crow -- a set of laws that made African Americans second-class citizens in the United States -- followed. Everything was supposed to be separate and equal. But it was all but equal.

African Americans were forced to live in a Jim Crow world that was very different from the world inhabited by most white Americans. Along the tidal Delaware, these different worlds were visible in many places -- on the river itself; on the ocean into which it flowed; and along the Philadelphia docks.

You could see these different worlds along the Delaware River and Bay, where, in the spring, shad turned the river silver as they swam in from the Atlantic to their breeding grounds. At the turn of the century, shad fisheries lined the banks; they were owned by whites. If you were African American, you could get a job rowing a skiff, or pulling in shad nets. Most jobs open to African Americans were, in this Jim Crow period, low-paying and low status.

These different worlds were also visible at sea, for centuries a place of opportunity for black seamen. In the early 1900s, that changed. Opportunities dwindled. If you were African American, the only job open to you aboard ship was as a steward or cook.

And these different worlds were visible along the Philadelphia docks, where, in the early 1900s, 6 out of 10 longshoremen were African American. Working conditions were bad, and whites were paid more than blacks doing the same job -- until the Industrial Workers of the World entered the picture. While many unions in the United States excluded African Americans, the IWW welcomed them. For a brief moment, it was a shining example of what labor could be. By the end of the 1920s, though, the IWW was replaced by the International Longshoremen's Association, which reintroduced the Jim Crow policies of unequal pay and opportunity.

As Yard No. 4 would show, the struggle to redefine freedom was still at force in the 1940s; it would continue for decades to come. For each story of progress there was another of rights taken away. For each time of hope was another of disillusionment.

The Delaware's tides, ebbing and flowing, continued to be an apt metaphor for the changing nature of freedom. It would take the 1960s, and the advent of the Civil Rights movement, to put forward a new vision of what life, freedom, and citizenship could be.

Next installment: Civil Rights

The image is the front cover of the October 1943 issue of "Our Yard," Illustrated by William Smith (b. 1921), Courtesy of the Collections of Independence Seaport Museum and the Sun Ship Historical Society

Ellen M. Snyder-Grenier is an independent curator, exhibition developer, and writer, and principal of REW & Co.